The Cold War: A MILITARY History (30 page)

Table 14.3

shows the number of warheads on the missiles, and is an indication (ignoring dummy silos) of how many targets could have been attacked, bearing in mind that pinpoint targets would probably have been targeted by two warheads. When compared with

Table 14.2

it shows that, whereas there was little prospect of a successful pre-emptive strike in 1970, both sides had obtained such a capability by 1980. The table also shows that the increase in numbers of warheads on the US side was greatest on SLBMs, while in the USSR the growth was greater on ICBMs, and that by 1990 the Soviet Union possessed a marked advantage in overall warhead numbers.

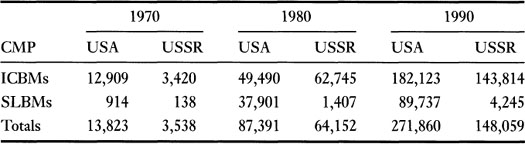

Table 14.4

The Strategic Balance – Counter-Military Potential (CMP)

Table 14.4

takes the balance a stage further and compares the CMP of the two forces. From this it is clear that the power of the missile forces of both sides increased greatly during the period: by a factor of twenty for the USA and of forty-two for the USSR. The table also shows that the Soviet counter-military potential was concentrated in its ICBM force, leaving the counter-value role to the submarine-based missiles. It is also clear, however, that neither side had an advantage over the other.

fn1

The figures in

Tables 14.2

to

14.4

are derived from the detailed tables in

Appendix 17

.

PART III

NAVAL WARFARE

15

The NATO Navies

COMMAND OF THE

seas was at least as important in the Cold War as it had been at any time in history. Indeed, for both the USA and the USSR it became more important than ever with the development of nuclear-powered submarines carrying long-range ballistic missiles with the ability to deliver strategic weapons of devastating power against land targets anywhere in the world. In terms of surface warfare, however, the Cold War had a different importance to the two alliances, since NATO depended on the sea, while the Warsaw Pact did not.

The USA was able to deploy aircraft carriers, with their increasingly potent air wings, to any part of the world, while for NATO the Atlantic Ocean was the sea line of communication (SLOC) along which huge numbers of men and vast quantities of heavy military equipment would travel to support Europe in time of war. The sea was also the means by which many NATO forces would be deployed or redeployed, particularly to the flanks, depending upon the Soviet threat; thus the great majority of reinforcements for Norway, Denmark and Turkey were all scheduled to arrive by sea. In addition, western Europe would have required vast amounts of oil – much more in war than in peace – which would have had to continue to be brought to European oil terminals.

For the Warsaw Pact, naval surface warfare was of considerably lesser importance, since it was not essential for survival. Thus Warsaw Pact nations with access to the sea maintained only small navies – with the sole exception of the USSR, which built up a sizeable fleet, but principally in order to provide a counter to US naval might.

The opening balance between NATO and Soviet naval forces is shown in

Appendix 18

.

THE US NAVY

The United States navy emerged from the Second World War as the largest, most efficient and best-equipped navy in the world. The Japanese

navy

had been the only force able to challenge US naval power in the Pacific, but it had now ceased to exist, as had the German and Italian navies across the Atlantic. The UK, on the other hand, had entered the war as the world’s strongest naval power and its navy had expanded rapidly between 1939 and 1945, but, even so, it had failed to match the phenomenal growth of the US navy. As a result, in the early post-war years the British found that, while they were still strong, they had nevertheless been relegated to second place – a position they initially found hard to accept, as the row over the demand that a British admiral be SACLANT in the early 1950s showed. The traditional friendship between the US and UK navies, which had become even closer during the war, did, however, make the change in status less unpleasant than it might otherwise have been and, once the British had adjusted, the two navies continued to enjoy a very close relationship.

The US navy found itself in 1946 with a role that was not very clear-cut and a huge surplus of warships, many of them less than three years old. The active fleet was reduced dramatically, building programmes were cut to the bone, many ships were transferred to allies or scrapped, and the remainder – still a large number – were placed in reserve. Development work continued, including detailed examination of German designs and many tests of captured German equipment, particularly missiles and submarines, but it was the emergence of the Soviet threat, particularly in Europe, that first provided a post-war focus for the fleet.

The establishment of NATO, coupled with the military weakness of the west-European nations, made it inevitable that the United States would become involved in any conflict in Europe and that the majority of its help would go by sea. Maintaining the sea lines of communication across the north Atlantic thus became a major commitment, taking two forms: anti-surface operations against Soviet navy surface groups and anti-submarine operations.

The United States’ position in the world also meant that the navy had to undertake missions in the Third World in support of the national policy of containing Communist expansion. This involved active naval operations in Korea and Vietnam, as well as in numerous minor conflicts, such as in Lebanon. The major confrontation throughout the Cold War period, however, was with the Soviet navy, where the US navy saw its potential enemy grow from a relatively minor coastal force to the second greatest navy in the world.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s the main emphasis was placed on carrier groups which would carry bombers to attack the Soviet navy’s ship and air bases supporting the Northern, Baltic and Black Sea fleets. The growing numbers of Soviet submarines were countered by a variety of means. There were large numbers of Second World War destroyers and frigates still available

which

were capable of accommodating the anti-submarine-warfare sensors and weapons of the time, as well as large numbers of ASW aircraft. Also, in the late 1940s a new type of ‘hunter/killer’ submarine was developed, which was equipped with large and highly sensitive sonars and whose intended mission was to wait off Soviet naval bases and to attack enemy submarines as they deployed; it was, however, not a success, and attention returned to more traditional designs. The US navy also devoted considerable funds to the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), a series of microphones lying on the seabed across choke points such as the Greenland–Iceland–UK gap and linked by seabed cables to control centres ashore, which gave advance warning of submarine deployments.

One of the key developments was the introduction of nuclear propulsion for both submarines and surface ships, which was masterminded by one of the most remarkable figures of the post-war era in any navy: Admiral Hyman Rickover.

fn1

He applied nuclear propulsion to submarines and later to aircraft carriers and cruisers, producing ships whose endurance was limited only by that of the crew, although the nuclear carriers still needed to be replenished with fuel, weapons and ammunition for the air wing.

The Vietnam War was a major preoccupation for the US navy for over a decade, but the absence of any significant naval opposition meant that naval air and surface power could be used almost totally in support of the land battle. Despite its many commitments in the Pacific and other areas, however, the north Atlantic was the principal concern of the US navy throughout the Cold War, and virtually all US ship designs were judged against their value in a potential Atlantic conflict against the Soviet navy.

For many years the ‘massive retaliation’ and ‘tripwire’ strategies meant that any war in Europe would escalate fairly rapidly to a nuclear conflict. This, almost by definition, would be of relatively short duration; thus war stocks of ammunition, fuel and supplies in western Europe were relatively small, and there would have been little point in fighting expensive convoy battles across the Atlantic. Once the strategy changed to that of ‘flexible response’, however, it became possible that the war would be much longer and that fresh supplies of both men and

matériel

would have to be transported to Europe across the Atlantic.

In the 1970s, therefore, the US navy faced up to the new requirement, setting itself a goal of a ‘600-ship’ navy. Large-scale building plans were initiated, and the programme was well under way when the Cold War came to an abrupt halt. The plans were then very quickly adjusted downwards, with

orders

cancelled, building slowed down, and many older vessels scrapped before the scheduled end of their operational lives.

Throughout the Cold War, one of the key components in the US navy’s ability to deploy overseas was its under-way replenishment force. This comprised a large number of specialist vessels which could resupply warships with all their needs, enabling them to undertake operations anywhere in the world’s oceans and for an almost unlimited time. The most sophisticated of them, the Sacramento class, carried 177,000 barrels of fuel oil, 1,950 tonnes of munitions, 225 tonnes of dry stores and 225 tonnes of refrigerated stores, and had a speed of 26 knots, enabling them to keep pace with a carrier task group.

One of the great achievements of the US navy during the Cold War was that it posed a very direct threat to any Soviet war plans. It could sustain movement along the transatlantic SLOC; it threatened the Soviet navy’s fleet of SSBNs, even in their bastions; its carrier groups threatened attacks against major naval bases; its SSBNs threatened the very survival of the USSR; and the amphibious-warfare groups threatened landings on the Soviet flanks. Finally, the US navy possessed two intangible assets in its prestige as one of the major victors in the Second World War and in its ability to deploy large and impressive ships anywhere in the world. The combination of these factors led the Soviet Union to undertake a major naval expansion and building programme, which proved not only to be extremely costly but also to be one of the key components in its eventual collapse.

The predominance of the United States navy in the Cold War was beyond anything that had gone before – except, perhaps, the British navy at the height of its influence in the late Victorian era. Between 1945 and 1990 the US navy produced ships of a size, complexity and sophistication far beyond the capability of any other navy, and in numbers which no other nation could match. To take just four examples: thirteen supercarriers were built, thirty-one Spruance-class destroyers, sixteen Ticonderoga-class cruisers and thirty-eight Los Angeles-class SSNs, all of them world-leaders in their types.

fn2

OTHER NATO NAVIES

All NATO nations except Luxembourg and Iceland contributed naval forces to the Alliance. These navies were of varying sizes and degrees of sophistication, and were developed and organized according to each nation’s perceptions of its requirements. A degree of standardization was achieved in areas

such

as station-keeping, weaponry, communications, data links, replenishment techniques and some equipment, although the basic ship designs and tactical deployments were a national responsibility. Standardization was also achieved as a consequence of international programmes, particularly those involving ships procured under US aid programmes.

Belgium

Belgium’s allotted NATO maritime roles included the defence, in conjunction with its allies, of the North Sea, the English Channel and the Western Approaches. The early post-war expansion programme was based on ex-US and ex-British warships, but four Belgian-designed frigates were constructed in the 1970s and ten ‘Tripartite’ (Belgium, France and the Netherlands) minehunters in the 1980s.

Canada

The Canadian navy expanded from very small beginnings in 1939 into a sizeable and efficient force by 1945, and it endeavoured to maintain a large-ship capability in the early post-war years, operating an aircraft carrier and two cruisers, all of British design. The financial and manpower costs were, however, too great, and the two cruisers were paid off in the 1960s and the aircraft carrier in 1970. Thereafter the navy concentrated on its NATO-assigned ASW mission in the North Atlantic, for which it built a series of escort vessels of unique design and pioneered the use of ASW helicopters from small warships. The Canadians also operated a small number of submarines and some minesweepers.

Denmark

Denmark had virtually no navy at the war’s end in 1945, but on joining NATO in 1949 it was allotted the role of Baltic defence, in which it was joined by West Germany when the latter became a NATO member in 1955. Denmark’s second naval task was the mining of the Kattegat and the Belts to deny the Soviet fleet an exit into the North Sea. The navy also had the national task of patrolling Greenland waters.

To fulfil these missions, the Danish navy maintained a small number of frigates, all designed and built in Denmark, together with three unusual corvettes (Nils Juel class), and also provided a small number of submarines and fast-attack craft. To meet its minelaying commitment the Danish navy was equipped with a number of dedicated minelayers.