The Cold War: A MILITARY History (50 page)

The Dutch also developed an 8 × 8-wheeled APC, the YP-408, a large vehicle which was based on a DAF truck and accommodated a crew of two

and

ten infantrymen. It served in the Dutch army from 1964 until being replaced by the US-designed tracked AIFV from 1977 onwards. The British also used a wheeled APC, the 6 × 6-wheeled Saracen, in the 1960s, but it was employed mainly by the support troops in reconnaissance units and only rarely by infantry battalions.

The French army used wheeled APCs for roles outside Europe, but for European warfare it used tracked APCs, all of French design. The first was the AMX VCI, which entered service in 1957 and was based on the AMX-13 light tank. It had a troop compartment accommodating ten infantrymen, with eight facing outwards and two to the rear, all of them with firing ports. The VCI was replaced from 1973 onwards by the AMX-10P, an all-aluminium vehicle, armed with a 20 mm cannon on an external mount. It carried eight infantrymen, but these did not have the ability to fight from inside the vehicle.

From 1963 onwards the British also used a tracked APC, the FV432, which was generally similar in design to the M113, but constructed of steel. In the 1970s, however, when the British army started to consider a replacement for the FV432, there was an intense internal debate over the future requirement, which centred upon whether a new vehicle should be a MICV, as exemplified by the German Marder, or simply a better APC. Various prototypes were designed and tested, including a very large MICV, but in the end the Mechanized Combat Vehicle-80 (MCV-80) was selected, mounting a 30 mm Rarden cannon, and carrying eight infantrymen (one of whom was also the vehicle commander), although they did not have firing ports and therefore could not use their weapons from inside the vehicle. The title, MCV-80, was intended to demonstrate that the vehicle would enter service in 1980, but, as so often happened when such dates were included in a weapon title (e.g. the German/US MBT-70 tank), this proved to be over-optimistic and the vehicle did not enter service until 1987.

THE INFANTRY REVOLUTION

Fielding APCs and MICVs represented a true revolution in the infantry, since the men were all mounted, together with their weapons, equipment and supplies, while the tracks gave them a mobility virtually identical with that of tanks; in addition, since every vehicle was fitted with a radio (and the radio was no longer limited in size by the need for it to be carried on a man’s back), commanders were able to achieve an unprecedented degree of control. Further, the vehicles were able to carry heavy machine-guns or cannon in turrets, as well as lighter machine-guns and anti-tank guided weapons, greatly increasing the firepower available.

Later it was also realized that, by creating a slight overpressure inside,

these

vehicles could provide collective protection against chemical and biological weapons. APCs/MICVs also proved remarkably adaptable, forming the basis for many specialist vehicles for use as command posts, ambulances, communications stations, recovery and repair vehicles, and minelayers. As a result they were produced in considerable numbers

There were, of course, some penalties. Each APC required a driver and a commander, which meant that every section was robbed of two men on the ground – a significant number of men when a battalion was equipped with some sixty or more APCs. In addition, the battalion’s logistic requirements increased dramatically, principally for fuel and spares, while the maintenance requirement also increased.

The change in capability can be gauged by a brief examination of the infantry battalion in the British army, whose experiences were typical of the changes in all armies. In the 1950s a British infantry battalion consisted of some 700 men, for the majority of whom the normal means of movement was on foot. There were three rifle companies, in which the vast majority of men were armed with a 7.70 mm bolt-action rifle, although each rifle platoon also had three 7.70 mm light machine-guns and three 51 mm mortars. The heavy-weapons company operated six 7.70 mm Vickers heavy machine-guns, six 120 mm WOMBAT recoilless anti-tank guns and six 76.2 mm mortars. Mobility was limited to approximately twenty Jeeps or Land Rovers, mainly for commanders and communicators, and twenty three-tonne trucks, whose primary purpose was logistic resupply.

In the late 1980s a British mechanized battalion was still approximately the same size – 725 men – but now every one of these had his own allotted place in a vehicle. All men carried an automatic weapon, the riflemen carrying the British standard 5.56 mm rifle. The battalion operated 157 vehicles, comprising 90 MCV-80 Warrior IFVs, 19 tracked reconnaissance vehicles, 16 Land Rovers, and 4 one-tonne, 17 four-tonne and 11 eight-tonne trucks. Heavy weapons included eight 81 mm mortars, twelve Milan anti-tank guided-missile launchers, and a large quantity of 30 mm Rarden cannon and 7.62 mm machine-guns mounted on the Warriors. Logistic resupply had, however, become a severe problem, especially for fuel, ammunition and spares, while the maintenance requirement was met a by a platoon of twenty-eight men. All IFVs had at least one radio, as did most Land Rovers. The greatest change, however, was in the infantry’s mobility, since it had become fully capable of moving cross-country in company with tanks or of moving at high speed along roads.

fn1

‘6 × 6’ indicates that it was a six-wheeled vehicle with all six wheels powered. A 4 × 2 vehicle has four wheels with only two powered (as in a standard civil automobile).

27

Artillery

FIELD ARTILLERY

The Guns

WHILE THE TANK

became the public and political symbol of an army’s military prowess, overshadowing other battlefield weapons systems, within armies the importance of the artillery arm remained undiminished and, despite the advent of missiles and rockets, the gun remained the weapon of choice in the tactical battle.

fn1

Provided targets were within range, guns were capable of producing extremely accurate and very destructive fire at virtually any spot selected by battlefield commanders. Further, artillery command-and-control systems enabled the guns to switch targets quickly and to increase the weight of fire by bringing additional batteries into action as required.

Artillery was of great importance in the Second World War, and this continued in the many smaller wars between 1945 and 1990, when the tactical value of artillery was demonstrated repeatedly, although never more convincingly than at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu during the First Indo-China War. During that prolonged siege, which lasted from December 1953 to May 1954, Viet Minh artillery occupied the hills overlooking the French base and from there they totally dominated the battlefield, closed the airfield, cut off supplies, and eventually bludgeoned the garrison into defeat.

In the early 1950s there were only a small number of self-propelled guns, all in open mounts on converted tank chassis, which supported armoured divisions in some armies (e.g. the British and US). The great majority of

guns

were wheeled pieces, towed either by a specially designed artillery tractor or, in some cases, by an ordinary general-purpose truck. At a US army conference held in Washington in January 1952 it was decided that the speed of modern warfare was increasing to such an extent, particularly with the infantry planning to be mounted entirely in armoured personnel carriers, that wheeled guns would no longer be able to keep up with the speed of movement. Also, the threat of nuclear weapons made it necessary to place the crews inside closed gun-houses (turrets) for protection. Furthermore, tracked vehicles were more capable of moving into temporary fire positions, getting into and out of action quickly, since there was no need to separate the gun from its tractor and set it on a base-plate. Then, after firing, they could move out rapidly – the so-called ‘shoot-and-scoot’ tactic – before enemy artillery could determine the source of the rounds and fire a counter-battery mission.

The US army initiative resulted in three outstanding designs – the M107 (175 mm), M109 (155 mm), and M110 (203 mm) – although the M109 was the only one to provide a gun-house to shelter the crew. These weapons came to dominate the NATO artillery arms, seeing service in virtually every NATO army except that of France. US army deployment, which was typical of other NATO armies was fifty-four M109 155 mm and twelve M110 203 mm in each armoured and mechanized infantry division, and twelve M107 175 mm in each corps.

The great majority of other NATO nations simply followed the US lead on artillery tactics and adopted US weapons, and only a few other guns were developed. The British produced the 105 mm Abbot tracked SP gun in the 1960s, but within NATO this served only with the British army, since it was by then clear that the future lay with the larger 155 mm calibre. The British did, however, collaborate with Germany and Italy in the successful 155 mm Field Howitzer 1970 (FH70) programme, producing a towed gun which was destined for use in ‘out-of-area’ roles by the UK and by territorial defence units in the FRG and Italy. The success of the FH70 led to a follow-on collaborative project with Germany, the ambitious SP70, a 155 mm self-propelled, tracked weapon, using the same ordnance as the FH70. Unfortunately it proved to be too ambitious, and after a great deal of expenditure it was eventually cancelled and the two countries went their separate ways.

The only other NATO nation to retain a significant domestic artillery industry was France, which produced a series of towed and self-propelled artillery pieces. The French retained towed guns for use by their front-line mechanized infantry divisions, even producing the new TR 155 mm towed gun in the 1970s, at a time when all other European armies had long since converted to self-propelled pieces.

Soviet artillery had established an awesome reputation during the Second World War, but for the next two decades it experienced a conservatism

unusual

in the Soviet armed forces, which not only adhered to towed artillery, but also invariably deployed it in rows of six guns in uncamouflaged fire positions. Well-established Second World War guns therefore remained in service throughout the 1950s, and their replacements in the 1960s were also towed. It was only in the 1970s that self-propelled guns came into service, in which existing tracked chassis were matched to modified versions of existing guns, producing systems of 122 mm, 152 mm and 203 mm calibre. Although long overdue, these proved to be of excellent quality, with the usual Soviet combination of practical design, simplicity and long range, and caused considerable alarm in the West.

Czechoslovakia made a notable contribution to artillery design with its DANA system, which entered service in 1981. This featured a 152 mm gun in a split turret mounted on a modified 8 × 8-wheeled truck chassis. Although the wheels reduced its cross-country capability in comparison with a tracked vehicle, its performance was more than adequate for service in central Europe with its excellent road systems, and any tactical disadvantages were offset by its high road speed, long road range, considerably reduced capital cost, and ease of maintenance.

Calibres

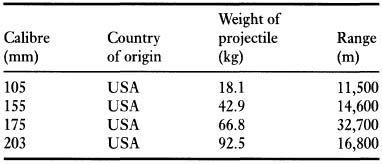

In the 1950s NATO armies were equipped with guns of a wide variety of calibres, and in one of its early efforts at standardization NATO decided on the 105 mm round. France, the UK and the USA all produced self-propelled guns of this calibre in the 1950s and 1960s, but the shells had limited carrying capacity, lethality and range compared to those of 155 mm (as shown in

Table 27.1

), and 155 mm subsequently became the NATO standard for field artillery.

Table 27.1

NATO Standard High-Explosive Ammunition

The varieties of payload also increased considerably during the Cold War. US army 155 mm rounds, for example, could carry high explosives (HE); chemical agents; direct-fire anti-tank; flares; smoke; anti-tank minelets; anti-personnel minelets; and self-forming, top attack, anti-tank munitions.

Warsaw

Pact countries produced similar payloads, and also developed a communications jammer housed in a 152 mm shell.

Great efforts were also made to extend the range. One method was by lengthening the barrel; virtually doubling the length of the 203 mm barrel in the US M110, for example, increased the range of the M106 HE projectile from 16,800 m to 21,300 m. Shell design was also progressively refined, with techniques such as base bleed and rocket assistance both being used to enhance the range. Somewhat to the frustration of Western designers, however, Soviet designers always seemed to be able to obtain greater range than their Western counterparts: for example, the Soviet 152 mm gun fired a 43.5 kg shell to 24,000 m, while the US 155 mm fired a 42.9 kg shell to 14,600 m.

Nothing is ever achieved without penalty, however, and the consequence of increasing the calibre was that individual rounds were heavier, meaning that fewer could be carried on the gun, while the increase in firing rate meant that more rounds were required from the logistics system, and the increase in range placed new requirements on the target-acquisition process.