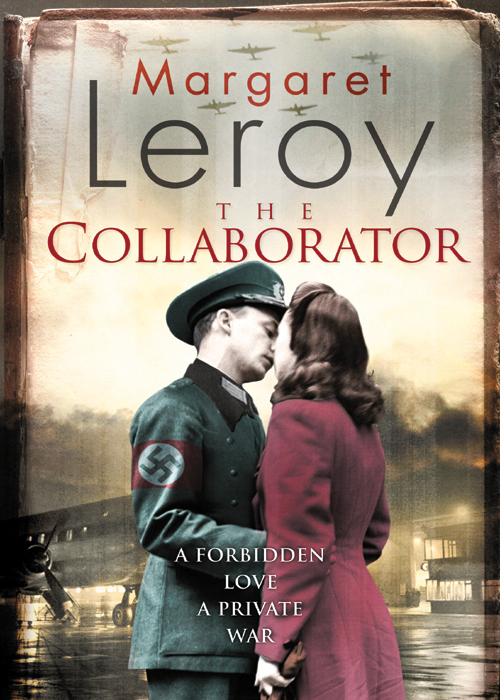

The Collaborator

Authors: Margaret Leroy

Acclaim for

MARGARET LEROY

“Margaret Leroy writes with candour and intelligence, capturing the menace of suddenly finding the world may not be at all as you’ve thought it.”

—Helen Dunmore “Leroy handles … domestic life with the same graceful, precise rueful style as [Richard Yates] the late novelist did, though with a warmer, more hopeful intelligence.”

—Washington Post

“Engrossing and affecting.”

—Eve

“Brilliant at portraying the slow, steady disintegration of a seemingly ordinary life when secrets are unearthed and dark suspicions spread.”

—Baltimore Sun

“Powerful and haunting.”

—Daily Mirror

“What a storyteller Leroy is, and what an eye she has for contemporary life.”

—Fay Weldon

“[Leroy’s] quiet, self-assured narrative voice delivers tremendous psychological depth and emotional resonance.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Leroy expertly draws a picture of a woman and a family in crisis and the moral questions one sometimes has to face.”

—Toronto Sun

Acclaim for

The Drowning Girl

“Margaret Leroy’s eerily lovely novel … is one of those rare books you’ll sit with till your bones ache.”

—Oprah Magazine

“This is a really special book. Sylvie’s vulnerability is so powerfully drawn, so flesh-and-blood real, that you want to reach into the pages and protect her yourself.”

—Louise Candlish

“Compelling from the first chapter … It is a book I will never forget … Read it—it is such a refreshing change from the ususal frothy stories.”

—Candis Magazine

“This book is perfect for anyone wanting an intriguing story which is also well-written and moving … Really enjoyable book and perfect holiday reading.”

—Adele Geras

Acclaim for Margaret Leroy’s

The Perfect Mother

A

New York Times

Notable Book of the Year

“Written with a wonderfully convincing authority … I was eager to find out what happened next. I dreaded the worst and I hoped for the best—and I won’t tell you which happens.”

—New York Times

“Reads like a thriller and is brilliant at portraying the slow, steady disintegration of a seemingly ordinary life when secrets are unearthed and dark suspicions spread.”

—Baltimore Sun

MARGARET LEROY

studied music at Oxford. She has written four novels, one of which was televised by Granada and reached an audience of eight million. Margaret has appeared on numerous radio and TV programmes, and her articles and short stories have been published in the

Observer,

the

Sunday Express

and the

Mail

on Sunday. Her books have been translated into ten languages. Margaret is married with two daughters and lives in Surrey.

ISBN: 9781742906102

TITLE: The Collaborator

First Australian Publication 2011

Copyright © 2011 Margaret Leroy All rights reserved. Except for use in any review, the reproduction or utilisation of this work in whole or in part in any form by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, is forbidden without the permission of the publisher, Harlequin Mills & Boon®, Locked Bag 7002, Chatswood D.C. N.S.W., Australia 2067.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

MIRA and the Star Colophon are trademarks used under license and registered in Australia, New Zealand, Philippines, United States Patent and Trademark Office in other countries.

For questions and comments about the quality of this book please contact us at [email protected].

My thanks are due to my wonderfully thoughtful and perceptive editor, Maddie West, and the whole talented team at Mira; I am especially grateful to Kim Young, Oliver Rhodes, and Sue Smith, my meticulous copyeditor. Thank you as well to Brenda Copeland and Elisabeth Dyssegard at Hyperion in New York. I am also deeply grateful to my agents, Kathleen Anderson, and Laura Longrigg in London, who are so committed to my writing and who have supported me in so many ways. And thank you as always to Mick and Izzie, who shared Guernsey with me, and Becky and Steve, for so much love and encouragement.

Among the books that I read while researching

The Collaborator,

two deserve special mention—Madeleine Bunting’s fascinating history,

The Model Occupation,

and Marie de Garis’s enchanting volume,

Folklore of Guernsey.

‘Qui veurt apprendre a priaïr, qu’il aouche en mdïr.’

He who wishes to learn to pray, let him go to sea.

—Guernsey proverb

PART I:

JUNE 1940

‘“O

nce upon a time there were twelve princesses …’” My voice surprises me. It’s perfectly steady, the voice of a normal mother on a normal day—as though everything is just the same as it always was.

‘“Every night their door was locked, yet in the morning their shoes were all worn through, and they were pale and very tired, as though they had been awake all night …”’

Millie is pressed up against me, sucking her thumb. I can feel the warmth of her body: it comforts me a little.

‘They’d been dancing, hadn’t they, Mummy?’

‘Yes, they’d been dancing,’ I say.

Blanche sprawls out on the sofa, pretending to read an old copy of

Vogue

, twisting her long blonde hair in her fingers to try and make it curl. I can tell that she’s listening. Ever since her father went to England with the army, she’s liked to listen to her sister’s bedtime story. Perhaps it gives her a sense of safety. Or perhaps there’s something in her that yearns to be a child again.

It’s so peaceful in my house tonight. The amber light of the setting sun falls on all the things in this room—all so friendly

and familiar: my piano and heaps of sheet music, the Staffordshire dogs and silver eggcups, the many books on their shelves, the flowered tea set in the glass-fronted cabinet. I look around and wonder if we will be here this time tomorrow—if after tomorrow I will ever see this room again. Millie’s cat Alphonse is asleep in a circle of sun on the sill, and through the open window that looks out over our back garden you can hear only the blackbird’s song and the many little voices of the streams: there is always a sound of water in these valleys. I’m so grateful for the quiet—you could almost imagine that this was the end of an ordinary sweet summer day. Last week, when the Germans were bombing Cherbourg, you could hear the sound of it even here in our hidden valley, like thunder out of a clear sky, and up at Angie le Brocq’s farm, at Les Ruettes on the hill, when you touched your hand to the window pane, you could feel the faint vibration of it, just a tremor, so you weren’t quite sure if it was the window shaking or your hand. But for the moment, it’s tranquil here.

I turn back to the story. I read how there was a soldier coming home from the wars, who owned a magic cloak that could make him completely invisible. How he sought to discover the princesses’ secret. How he was locked in their bedroom with them, and they gave him a cup of drugged wine, but he only pretended to drink.

‘He was really clever, wasn’t he? That’s what I’d have done, if I’d been him,’ says Millie.

I have a sudden vivid memory of myself as a child, when she says that. I loved fairytales just as she does—enthralled by the transformations, the impossible quests, the gorgeous significant

objects—the magic cloaks, the satin dancing shoes; and, just like Millie, I’d fret about the people in the stories, their losses and reversals and all the dilemmas they faced. So sure that if I’d been in the story, it would all have been clear to me: that I’d have been wise and brave and resolute. I’d have known what to do.

I read on:

‘“When the princesses thought he was safely asleep, they climbed through a trapdoor in the floor, and he pulled on his cloak and followed. They went down many winding stairways, and came at last to a grove of trees, with leaves of diamonds and gold …’”

Briefly, I’m distracted by the charm of the story. I love this part especially, where the princesses follow the pathway down to another world, a secret world of their own, a place of enchantment—loving that sense of going deep, of being enclosed. Like the way it feels when you follow the Guernsey lanes down here to our home, in this wet wooded valley of St Pierre du Bois—a valley that seems so safe and cloistered, like a womb. Then, if you walk on, you will go up, up and out suddenly into the sunlight, where there are cornfields, kestrels, the shine of the sea. Like a birth.

Millie leans into me, wanting to see the pictures—the girls in their big, bright glimmery skirts, the gold and diamond leaves. I smell her familiar, comforting scent—of biscuits, soap and sunlight.

The ceiling creaks above us as Evelyn gets ready for bed. I have filled her hot-water bottle for her—she can feel a chill even on warm summer evenings. She will sit in bed for a while and read

the Bible. She likes the Old Testament best—the stern injunctions, the battles: the Lord our God is a jealous God. Our Rector at St Peter’s is altogether too gentle for her. When we go—

if

we go—she will stay with Angie le Brocq at Les Ruettes. Evelyn is far too old to travel—she’s like an elderly plant, too frail to uproot.

‘Mum,’ says Blanche, out of nowhere, in a little shrill voice. ‘Celeste says all the soldiers have gone—the English soldiers in St Peter Port.’ She speaks rapidly, as though the words are rising in her like steam. ‘Celeste says that there’s no one left to fight here.’

I take a breath: it hurts my chest. I can’t pretend any more. ‘Yes,’ I say. ‘I heard that. Mrs le Brocq told me.’ Now, suddenly, my voice seems strange—shaky, serrated with fear. It sounds like someone else’s voice. I bite my lip. ‘They’re coming, aren’t they, Mum?’ says Blanche. ‘Yes, I think so,’ I say.

‘What will happen to us if we stay here?’ she says. There’s a thrum of panic in her voice. Her eyes, blue as hyacinths, are urgent, fixed on my face. She’s chewing the bits of skin at the sides of her nails. ‘What will happen?’

‘Sweetheart—it’s a big decision. I’ve got to think it through …’

‘I want to go,’ she says. ‘I want to go to London. I want to go on the boat.’

‘Shut

up,

Blanche,’ says Millie. ‘I want to hear the story.’

‘Blanche—London isn’t safe.’

‘It’s safer than here,’ she says.

‘No, sweetheart. People are sending their children away to the country. The Germans could bomb London. Everyone has gas masks …’

‘But we could stay in Auntie Iris’s house. She said we’d be more than welcome in her letter, Mum. You

told

us. She

said

we could. I really want to go, Mum.’

‘It could be a difficult journey,’ I say. I don’t mention the torpedoes.

Her hands are clenched into fists. The bright sun gilds all the little fair hairs on her arms.

‘I don’t care. I want to go.’

‘Blanche, I’m still thinking …’

‘Well, you need to get a move on, Mum. We haven’t got for ever.’

I don’t know what to say to her. In the quiet, I’m very aware of the tick of the clock, like a heartbeat, beating on to the moment when I have to decide. It sounds suddenly ominous to me.

I turn back to the story.

‘“The princesses came to an underground lake, where there were twelve little boats tied up, and each with a prince to row it …’” As I read on, my voice steadies, and my heart begins to slow. ‘“The soldier stepped into the boat with the youngest princess. ‘Oh, oh, there is something wrong,’ she said. ‘The boat rides too low in the water.’ The soldier thought he would be discovered, and he was very afraid …’”

Blanche watches me, chewing her hand.

But Millie grins.

‘He doesn’t need to be frightened, does he?’ she says, triumphantly. ‘It’s going to be all right, isn’t it? He’s going to find out the secret and marry the youngest princess.’

‘Honestly, Millie,’ says Blanche, forgetting her fear for a moment, troubled by her little sister’s naivety. ‘He doesn’t realise that, does he? Anything could happen. The people in the story can’t tell how it’s going to end. You’re four, you ought to know that.’