The Collected Short Stories (54 page)

Read The Collected Short Stories Online

Authors: Jeffrey Archer

“As I explained, I fainted soon after he left the room. I phoned the police the moment I came to.”

“How convenient,” said Sir Matthew. “Or perhaps the truth is that you made use of that time to set a trap for your husband, while allowing your lover to get clean away.” A murmur ran through the courtroom.

“Sir Matthew,” the judge said, jumping in once again. “You are going too far.”

“Not so, M'Lud, with respect. In fact, not far enough.” He swung back round and faced my wife again.

“I put it to you, Mrs. Cooper, that Jeremy Alexander was your lover, and still is, that you are perfectly aware he is alive and well, and that if you wished to, you could tell us exactly where he is now.”

Despite the judge's spluttering and the uproar in the court, Rosemary had her reply ready.

“I only wish he were,” she said, “so that he could stand in this court and confirm that I am telling the truth.” Her voice was soft and gentle.

“But

you

already know the truth, Mrs. Cooper,” said Sir Matthew, his voice gradually rising. “The truth is that your husband left the house on his own. He then drove to the Queen's Hotel, where he spent the rest of the night, while you and your lover used that time to leave clues across the city of Leedsâclues, I might add, that were intended to incriminate your husband. But the one thing you couldn't leave was a body, because, as you well know, Mr. Jeremy Alexander is still alive, and the two of you have together fabricated

this entire bogus story simply to further your own ends. Isn't that the truth, Mrs. Cooper?”

you

already know the truth, Mrs. Cooper,” said Sir Matthew, his voice gradually rising. “The truth is that your husband left the house on his own. He then drove to the Queen's Hotel, where he spent the rest of the night, while you and your lover used that time to leave clues across the city of Leedsâclues, I might add, that were intended to incriminate your husband. But the one thing you couldn't leave was a body, because, as you well know, Mr. Jeremy Alexander is still alive, and the two of you have together fabricated

this entire bogus story simply to further your own ends. Isn't that the truth, Mrs. Cooper?”

“No, no!” Rosemary shouted, her voice cracking before she finally burst into tears.

“Oh, come, come, Mrs. Cooper. Those are counterfeit tears, are they not?” said Sir Matthew quietly. “Now you've been found out, the jury will decide if your distress is genuine.”

I glanced across at the jury. Not only had they fallen for Rosemary's performance, but they now despised me for allowing my insensitive bully of a counsel to attack such a gentle, long-suffering woman. To every one of Sir Matthew's probing questions, Rosemary proved well capable of delivering a riposte that revealed to me all the hallmarks of Jeremy Alexander's expert tuition.

When it was my turn to enter the witness box, and Sir Matthew began questioning me, I felt that my story sounded far less convincing than Rosemary's, despite its being the truth.

The closing speech for the Crown was deadly dull, but nevertheless deadly. Sir Matthew's was subtle and dramatic, but I feared less convincing.

After another night in Armley Jail I returned to the dock for the judge's summing up. It was clear that he was in no doubt as to my guilt. His selection of the evidence he chose to review was unbalanced and unfair, and when he ended by reminding the jury that his opinion of the evidence should ultimately carry no weight, he only added hypocrisy to bias.

After their first full day's deliberations, the jury had to be put up overnight in a hotelâironically, the Queen'sâand when the jolly little fat man in the bow tie was finally asked: “Members of the jury, do you find the prisoner at the bar guilty or not guilty as charged?” I wasn't surprised when he said clearly for all to hear, “Guilty, My Lord.”

In fact I was amazed that the jury had failed to reach a unanimous decision. I have often wondered which two members felt convinced enough to declare my innocence. I would have liked to thank them.

The judge stared down at me. “Richard Wilfred Cooper, you have been found guilty of the murder of Jeremy Anatole Alexander ⦔

“I did not kill him, My Lord,” I interrupted in a calm voice. “In fact, he is not dead. I can only hope that you will live long enough to realize the truth.” Sir Matthew looked up anxiously as uproar broke out in the court.

The judge called for silence, and his voice became even more harsh as he pronounced, “You will go to prison for life. That is the sentence prescribed by law. Take him down.”

Two prison officers stepped forward, gripped me firmly by the arms, and led me down the steps at the back of the dock into the cell I had occupied every morning for the eighteen days of the trial.

“Sorry, old chum,” said the policeman who had been in charge of my welfare since the case had begun. “It was that bitch of a wife who tipped the scales against you.” He slammed the cell door closed and turned the key in the lock before I had a chance to agree with him. A few moments later the door was unlocked again, and Sir Matthew strode in.

He stared at me for some time before uttering a word. “A terrible injustice has been done, Mr. Cooper,” he eventually said, “and we shall immediately lodge an appeal against your conviction. Be assured, I will not rest until we have found Jeremy Alexander and he has been brought to justice.”

For the first time I realized Sir Matthew knew that I was innocent.

I was put in a cell with a petty criminal called Fingers Jenkins. Can you believe, as we approach the twenty-first century, that anyone could still be called “Fingers”? Even so, the name had been well earned. Within moments of my entering the cell, Fingers was wearing my watch. He returned it immediately I noticed it had disappeared. “Sorry,” he said. “Just put it down to 'abit.”

Prison might have turned out to be far worse if it hadn't been known by my fellow inmates that I was a millionaire,

and was quite happy to pay a little extra for certain privileges. Every morning the

Financial Times

was delivered to my bunk, which gave me the chance to keep up with what was happening in the City. I was nearly sick when I first read about the takeover bid for Cooper's. Sick not because of the offer of £12.50 a share, which made me even wealthier, but because it became painfully obvious what Jeremy and Rosemary had been up to. Jeremy's shares would now be worth several million poundsâmoney he could never have realized had I been around to prevent a takeover.

and was quite happy to pay a little extra for certain privileges. Every morning the

Financial Times

was delivered to my bunk, which gave me the chance to keep up with what was happening in the City. I was nearly sick when I first read about the takeover bid for Cooper's. Sick not because of the offer of £12.50 a share, which made me even wealthier, but because it became painfully obvious what Jeremy and Rosemary had been up to. Jeremy's shares would now be worth several million poundsâmoney he could never have realized had I been around to prevent a takeover.

I spent hours each day lying on my bunk and scouring every word of the

Financial Times

. Whenever there was a mention of Cooper's, I went over the paragraph so often that I ended up knowing it by heart. The company was eventually taken over, but not before the share price had reached £13.43. I continued to follow its activities with great interest, and I became more and more anxious about the quality of the new management when they began to fire some of my most experienced staff, including Joe Ramsbottom. A week later I wrote and instructed my stockbrokers to sell my shares as and when the opportunity arose.

Financial Times

. Whenever there was a mention of Cooper's, I went over the paragraph so often that I ended up knowing it by heart. The company was eventually taken over, but not before the share price had reached £13.43. I continued to follow its activities with great interest, and I became more and more anxious about the quality of the new management when they began to fire some of my most experienced staff, including Joe Ramsbottom. A week later I wrote and instructed my stockbrokers to sell my shares as and when the opportunity arose.

It was at the beginning of my fourth month in prison that I asked for some writing paper. I had decided the time had come to keep a record of everything that had happened to me since that night I had returned home unexpectedly. Every day the prison officer on my landing would bring me fresh sheets of blue-lined paper, and I would write out in longhand the chronicle you're now reading. An added bonus was that it helped me to plan my next move.

At my request, Fingers took a straw poll among the prisoners as to who they believed was the best detective they had ever come up against. Three days later he told me the result: Chief Superintendent Donald Hackett, known as the Don, came out top on more than half the lists. More reliable than a Gallup Poll, I told Fingers.

“What puts Hackett ahead of all the others?” I asked him.

“'e's honest, 'e's fair, you can't bribe 'im. And once the

bastard knows you're a villain, 'e doesn't care 'ow long it takes to get you be'ind bars.”

bastard knows you're a villain, 'e doesn't care 'ow long it takes to get you be'ind bars.”

Hackett, I was informed, hailed from Bradford. Rumor had it among the older cons that he had turned down the job of assistant chief constable for West Yorkshire. Like a barrister who doesn't want to become a judge, he preferred to remain at the coalface.

“Arrestin' criminals is 'ow 'e gets his kicks,” Fingers said, with some feeling.

“Sounds just the man I'm looking for,” I said. “How old is he?”

Fingers paused to consider. “Must be past fifty by now,” he replied. “After all, 'e 'ad me put in reform school for nickin' a tool set, and that was”âhe paused againâ“more than twenty years ago.”

When Sir Matthew came to visit me the following Monday, I told him what I had in mind, and asked his opinion of the Don. I wanted a professional's view.

“He's a hell of a witness to cross-examine, that's one thing I can tell you,” replied my barrister.

“Why's that?”

“He doesn't exaggerate, he won't prevaricate, and I've never known him to lie, which makes him awfully hard to trap. No, I've rarely got the better of the chief superintendent. I have to say, though, that I doubt if he'd agree to become involved with a convicted criminal, whatever you offered him.”

“But I'm not ⦔

“I know, Mr. Cooper,” said Sir Matthew, who still didn't seem able to call me by my first name. “But Hackett will have to be convinced of that before he even agrees to see you.”

“But how can I convince him of my innocence while I'm stuck in jail?”

“I'll try to influence him on your behalf,” Sir Matthew said after some thought. Then he added, “Come to think of it, he does owe me a favor.”

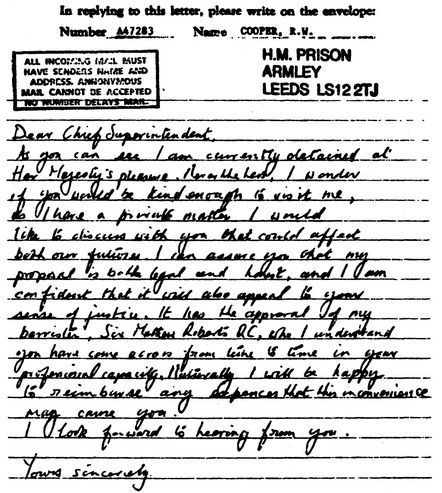

After Sir Matthew had left that night, I requested some more lined paper and began to compose a carefully worded

letter to Chief Superintendent Hackett, several versions of which ended crumpled up on the floor of my cell. My final effort read as follows:

letter to Chief Superintendent Hackett, several versions of which ended crumpled up on the floor of my cell. My final effort read as follows:

I reread the letter, corrected the spelling mistake, and scrawled my signature across the bottom.

At my request, Sir Matthew delivered the letter to Hackett by hand. The first thousand-pound-a-day postman in the history of the Royal Mail, I told him.

Sir Matthew reported back the following Monday that he had handed the letter to the chief superintendent in person. After Hackett had read it through a second time, his only comment was that he would have to speak to his superiors.

He had promised he would let Sir Matthew know his decision within a week.

He had promised he would let Sir Matthew know his decision within a week.

From the moment I had been sentenced, Sir Matthew had been preparing for my appeal, and although he had not at any time raised my hopes, he was unable to hide his delight at what he had discovered after paying a visit to the Probate Office.

It turned out that, in his will, Jeremy had left everything to Rosemary. This included over three million pounds' worth of Cooper's shares. But, Sir Matthew explained, the law did not allow her to dispose of them for seven years. “An English jury may have pronounced on your guilt,” he declared, “but the hard-headed taxmen are not so easily convinced. They won't hand over Jeremy Alexander's assets until either they have seen his body, or seven years have elapsed.”

“Do they think that Rosemary might have killed him for his money, and then disposed ⦔

“No, no,” said Sir Matthew, almost laughing at my suggestion. “It's simply that, as they're entitled to wait for seven years, they're going to sit on his assets and not take the risk that Alexander may still be alive. In any case, if your wife

had

killed him, she wouldn't have had a ready answer to every one of my questions when she was in the witness box, of that I'm sure.”

had

killed him, she wouldn't have had a ready answer to every one of my questions when she was in the witness box, of that I'm sure.”

I smiled. For the first time in my life I was delighted to learn that the tax man had his nose in my affairs.

Sir Matthew promised he would report back if anything new came up. “Goodnight, Richard,” he said as he left the interview room.

Another first.

It seemed that everyone else in the prison was aware that Chief Superintendent Hackett would be paying me a visit long before I was.

It was Dave Adams, an old jailbird from an adjoining cell, who explained why the inmates thought Hackett had

agreed to see me. “A good copper is never âappy about anyone doin' time for somethin' 'e didn't do. âackett phoned the governor last Tuesday, and 'ad a word with 'im on the Q.T., accordin' to Maurice,” Dave added mysteriously.

agreed to see me. “A good copper is never âappy about anyone doin' time for somethin' 'e didn't do. âackett phoned the governor last Tuesday, and 'ad a word with 'im on the Q.T., accordin' to Maurice,” Dave added mysteriously.

I would have been interested to learn how the governor's trusty had managed to hear both sides of the conversation, but decided this was not the time for irrelevant questions.

Other books

Button in the Fabric of Time by Dicksion, William Wayne

House of Holes by Nicholson Baker

Crimwife by Tanya Levin

Return From the Inferno by Mack Maloney

Snow Bound by Dani Wade

Babysitting the Billionaire by Nicky Penttila

Cherringham--The Vanishing Tourist by Neil Richards

Kentucky Sunrise by Fern Michaels

The Magnificent Showboats by Jack Vance

The Rogue's Princess by Eve Edwards