The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume 4 (55 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume 4 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

In the ordinary Buddhist tradition three is the nirmanakaya, sambhogakaya, and dharmakaya. Then if it is wished to emphasize the unity of the three and avoid any tendency to concretize them as separate, we speak of the whole as the svabhavikakaya. This is not a fourth kaya, but the unity of the three. The mahasukhakaya is a significant addition to this picture which came in with tantra.

Sukha

means “bliss”;

maha

means “than which there could be none greater.” So we have the peak experience again; and this is always felt as being, which gives kaya.

Kaya

is translated as “body,” but not in the sense of the purely physical abstraction which is often made in defining “body,” where we say that one thing is the mental aspect of us and the other thing is the physical aspect. This is a misconception. There is no such thing as a body without a mind. If we have a body without a mind, it is not a body, it is a corpse. It is a mere object to be disposed of. If we speak properly of a body, we mean something which is alive; and we cannot have a live body without a mind. So the two cannot be separated—they go together.

Thus the mahasukhakaya is an existential factor, which is of the highest value. This is not an arbitrary assignment of value that is made here. It is just felt that this is the only absolute value. This absolute value can be retrieved by reversing the process of error, of going astray; by reverting the energy that flows in one direction and becomes frozen, less active. It is this process of freezing which causes us to feel imprisoned and tied down. We are no longer free agents, as it were, but are in samsara.

So in answer to the question of whether or not there is some alternative to the continual frustration in which we live, the answer is yes. Let us find the initial, original, primordial, or whatever word you want to use—language is so limited—as a value. This is the mahasukhakaya.

The possibility of returning to the origin has been rendered manifest in the form of certain symbols of transformation, such as the mandala. Transformation from ordinary perception to primordial intrinsic awareness can take place when we try to see things differently, perhaps somewhat as an artist does. Every artist knows that he can see in two different ways. The ordinary way is characterized by the fact that perception is always related to accomplishing some end other than the perception itself. It is treated as a means rather than something in itself. But we can also look at things and enjoy their presence aesthetically.

If we look at a beautiful sunset, we can look at it as a physicist does and see it as a system of wavelengths. We lose the feeling of it completely. We can also look at it as a poignant symbol of the impermanence of all things and be moved to sadness. But this also is not just the sunset itself. There is a definite difference when we just look at it as it is and enjoy the vast play of colors that is there in tremendous vividness. When we look like this, we will immediately notice how free we become. The entire network of mental factors in which we usually labor just drops off. Everyone can do this but, of course, it requires work.

The art of the mandala has been developed to help us see things in their intrinsic vividness. Although all mandalas are fundamentally similar, each is also unique. The colors used in them, for instance, vary greatly according to the basic makeup of the practitioners. The character of a particular mandala is known as the dhatu-tathagatagarbha.

Dhatu

here refers to the factor of the particular individual makeup.

Tathagatagarbha

refers to the awakened state of mind or buddhahood. So a particular mandala could be seen as a specific index of the awakened state of mind. Care is taken to relate to individual characteristics because, although each person is capable of total buddhahood, he must start from the aspect of it that is most strongly present in him.

There is a Zen saying that even a blade of grass can become a Buddha. How are we to understand this? Usually we consider that a blade of grass simply belongs to the physical world; it is not even a sentient being, since it has no feelings, makes no judgments, has no perceptions. The explanation is that everything is of the nature of Buddha, so grass is also of this nature. It is not that it in some way contains buddha nature, that we can nibble away analytically at the various attributes of the blade of grass until there is nothing left but some vague leftover factor that we then pigeonhole as buddha nature. Rather, the blade of grass actually constitutes what we call buddhahood or an ultimate value.

It is in this sense that a blade of grass or any other object can be a symbol of transformation. The whole idea of symbols of transformation is made possible by the philosophical development of the Yogacharins, who saw that what comes to us in earthly vessels, as it were, the elements of our ordinary experience,

is

the fundamental mind, the ultimate value. The ultimate value comes in forms intelligible to us. Thus certain symbols such as mandalas, already partially intelligible to us, can be used as gateways to the peak experience.

So these symbols exist, differing according to the needs of individuals. We can slip into the world of running around in circles—that is what

samsara

literally means—or we can also, through such symbols, find our way out of it. But the way out is nowhere else but in the world where we are. There is no other world besides the world we live in. This is one of the main purports of Buddhist philosophy and one which Westerners often find hard to grasp. Buddhist philosophy does not make the distinction between the phenomenal and the noumenal. The phenomenon is the noumenon and the noumenon is the phenomenon; not in the sense of mathematical equation, but in the sense that you cannot have one without the other. The technical statement of this is that there is appearance and there is also shunyata; but shunyata is not somewhere else, it is in the appearance. It is its open dimension. The appearance never really implies any restriction or limitation. If there were such a limitation, we could never get out of it.

FOUR

The Mandala Principle and the Meditative Process

T

ANTRA CANNOT BE

understood apart from experience arising out of the practice of meditation. Tantra, as we have said, can be regarded as the golden roof of the house. Before we can put on a roof, we have first to have built a house, and before that even, to have laid a foundation. I have already mentioned the four foundation practices. But such practices by themselves are not enough; we have to do the basic work of relating to ourselves. The work we must do to have a complete understanding of the symbolism of tantra and of the mandala principle begins at a very rudimentary level.

A mandala consists of a center and the fringe area of a circle. On the basic level, it consists of the practitioner and his relationship to the phenomenal world. The study of the mandala principle is that of the student in his life situation.

In a sense spiritual practice in Buddhism in the beginning stages could be said to be very intellectual. It is intellectual in the sense of being precise. It could also be seen as intellectual because of the nature of the dialogue which has to take place between the student and the teacher, the student and the teaching. A certain questioning process has to take place. It is not a matter of memorizing texts or merely applying a variety of techniques. Rather it is necessary that situations be created in which the student can relate to himself as a potential Buddha, as a dharmabody—he relates his whole psyche or whole makeup to the dharma. He must begin with a precise study of himself and his situation.

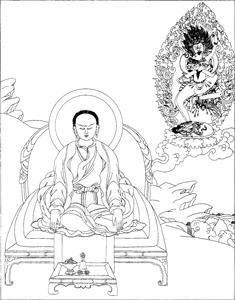

Marpa

(foreground)

and Two-Armed Hevajra

(background).

DRAWING BY TERRIS TEMPLE.

Traditionally there are twelve types of teaching styles proper to a Buddha. The sutras can be divided into twelve categories according to which of the twelve styles the Buddha has employed in it. One of the twelve styles is that of creating a situation in which the teaching can transpire. Take the example of the

Prajnaparamita-hridaya

or

Heart Sutra

. In the original Sanskrit version of this sutra, Buddha does not say a word; but it was Buddha who created the dialogue between Avalokiteshvara and Shariputra. Buddha created the situation in which Shariputra could act as the receiver or audience and Avalokiteshvara as the propounder of the analysis.

So creating the situation in which the student can relate to the teaching is the initial creation of the mandala principle. There is the hungry questioning, the thirsty mind which examines all possibilities. The questions are inspired by the basic suffering of the student’s situation, the basic chaos of it. It is uncertainty, dissatisfaction, which brings out the questions.

Seen in the tantric perspective, the first stages of the creation of the mandala principle are the basic Buddhist practices on the hinayana level. The starting point is samatha practice, which is the development of peace or dwelling on peace. This practice does not, however, involve dwelling or fixing one’s attention on a particular thing. Fixation or concentration tends to develop trancelike states. But from the Buddhist point of view, the point of meditation is not to develop trancelike states; rather it is to sharpen perceptions, to see things as they are. Meditation at this level is relating with the conflicts of our life situations, like using a stone to sharpen a knife, the situation being the stone. The samatha meditation, the beginning point of the practice, could be described as sharpening one’s knife. It is a way of relating to bodily sensations and thought processes of all kinds; just relating with them rather than dwelling on them or fixing on them in any way.

Dwelling or fixing comes from an attitude of trying to prove something, trying to maintain the “me” and “my” of ego’s territory. One needs to prove that ego’s thesis is secure. This is an attempt to ignore the samsaric circle, the samsaric whirlpool. This vicious circle is too painful a truth to accept, so one is seeking something else to replace it with. One seeks to replace the basic irritation or pain with the pleasure of a fixed belief in oneself by dwelling on something, a certain spiritual effort or just worldly things. It seems that, as something to be dwelled on, conceptualized ideas of religion or spiritual teachings or the domestic situations of life are extensions of the ego. One does not simply see tables and chairs as they are; one sees my manifestation of table, my manifestation of chair. One sees constantly the “me” or “my” in these things; they are seen constantly in relationship to me and my security.

It is in relation to this world of my projections that the precision of samatha is extremely powerful. It is a kind of scientific research, relating to the experiences of life as substances and putting them under the microscope of meditative practice. One does not dwell on them, one examines them, works with them. Here the curiosity of one’s mind acts as potential prajna, potential transcendental knowledge. The attitude of this practice is not one of seeking to attain nirvana, but rather of seeing the mechanism of samsara, how it works, how it relates to us. At the point of having seen the complete picture of samsara, of having completely understood its mechanism, nirvana becomes redundant. In what is called the enlightened state, both samsara and nirvana are freed.

In order to see thought processes (sensations and perceptions that occur during the practice of samatha) as they are, a certain sense of openness and precision has to be developed. This precise study of what we are, what our makeup is, is closely related with the practice of tantra. In the tantric tradition it is said that the discovery of the vajra body—that is, the innate nature of vajra (indestructible being)—within one’s physical system and within one’s psychological system is the ultimate experience. In the samatha practice of the hinayana tradition, there is also this element of looking for one’s basic innate nature as it is, simply and precisely, without being concerned over the absence of “me” and “my.”

From the basis of the samatha practice, the student next develops what is known as vipassana practice. This is the practice of insight, seeing clearly, seeing absolutely, precisely—transcendental insight. One begins to realize that spending one’s whole time on the details of life, as in the samatha practice, does not work. It is still somehow an adolescent approach. It is necessary to begin to have a sense of the totality. This is an expansion process. It is parallel with the tantric practice of the mandala. Having started with what is called the bija mantra, the seed syllable in the middle of the mandala, there is then the expanding process of discovering the four quarters of the mandala. Working with the seed syllable has the samatha quality of precision, looking at the definite qualities of things as they are. Having established the seed syllable, one puts other symbols around it in the four quarters, one expands one’s mandala. Similarly in the vipassana practice, having established the precision of details, one begins to experience the space around them. In other words, in making a pot, the importance is not so much on making the pot itself, but on shaping the space. Just so, in the vipassana practice the process is one of trying to feel the space around the pot. If one has a sense of the space one is going to create by producing a pot, one makes a good potter. But if one is purely concerned with making a shape out of clay without having a sense of the space, one does not make a good potter, or a good sculptor either, for that matter. In this way of beginning to relate with the space, vipassana is gradually letting go, a releasing and expanding.