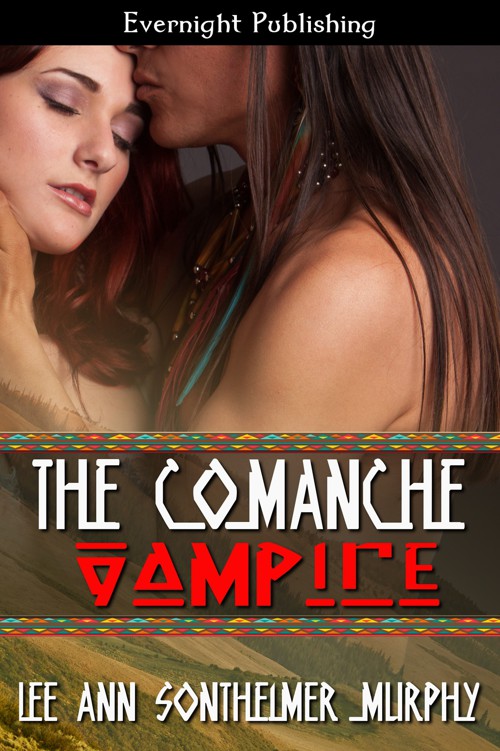

The Comanche Vampire

Read The Comanche Vampire Online

Authors: Lee Ann Sontheimer Murphy

Evernight

Publishing

Copyright© 2014 Lee Ann

Sontheimer

Murphy

ISBN: 978-1-77130-930-1

Cover

Artist: Sour Cherry Designs

Editor:

JC

Chute

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

WARNING:

The unauthorized reproduction or distribution of this copyrighted work is

illegal.

No part of this book may be

used or reproduced electronically or in print without written permission,

except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews.

This

is a work of fiction. All names, characters, and places are fictitious. Any

resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons, living or

dead, is entirely coincidental.

DEDICATION

For

my uncle, Raymond Neely, who once lived and dreamed in southwestern Oklahoma

and called Lawton home.

He shared his

appreciation for the Native American portion of our shared heritage with me and

he would enjoy this tale.

THE COMANCHE VAMPIRE

Lee Ann

Sontheimer

Murphy

Copyright © 2014

Prologue

June 2, 1875

Not

a breath of wind rippled the tall prairie grasses as the band of warriors rode

in silent defeat toward the fort.

Pea’hocso

stared toward the western horizon, at a blue sky

filled with thick white clouds.

They

would bring storms by evening and he wondered if the gods mourned with the

Quahadi

or raged at them.

Time would reveal which, he thought as his heart weighed heavier than

the oppressive summer heat.

Although

some of the others slumped,

Pea’hocso

sat straight and

tall, the way a Comanche warrior should.

He’d ride during these last moments of freedom with pride and

skill.

Saddle sore and heartsick, he

refused to yield anything to the Indian agent or

taibo

, the white man.

Often,

Pea’hocso

wished he’d died in battle. An honorable

death, and he would never have been forced to endure the coming bondage.

But although the

ta’siwoo

had all but vanished

from the earth,

Pea’hocso

would continue and outlive

the buffalo.

He just didn’t know why.

Quanah

Parker, son of Comanche Chief

Peta

Nocono

and a woman stolen from the whites long ago, led

their ragged band.

A year and a half ago,

Pea’hocso

counted a thousand warriors in the

Quahadi

, but less than four hundred rode behind their

leader now.

In their last war against

the

taibo

, the

final effort to expel the intruders from tribal lands and save their people,

they’d lost many: some to death. More to disease. And still more, who didn’t

wait.

Many

Comanche had trudged back, broken and bitter, to the reservation and tried to

learn the new ways.

Pea’hocso

rode among the final Comanche warriors, the last of the people to live free.

Their efforts had failed and so they returned, disgraced and broken, to Fort

Sill.

The 4

th

Cavalry had

driven them to this end, hounding them through the seasons under Colonel

McKenzie.

If Quanah hadn’t brought them

here, the blue coats had vowed to kill them.

Pea’hocso

thought it might’ve been better to

die as a warrior, but it hadn’t been his decision.

The

storm struck before they reached the Kiowa-Comanche Agency at the fort.

Winds howled with fury as rain descended from

the heavens and drenched everyone.

Accustomed to all weathers, none of the

Quahadi

flinched, but instead rode faster.

They

arrived on post in a wild tattoo of hoof beats and noise.

Lightning streaked the skies overhead with

vivid fire, and the voice of thunder boomed. The rain turned to hail, which pummeled

and punished

Pea’hocso

until he decided the gods were

angry.

It would’ve been better to die

free beneath the wide prairie sky than live confined by the white man, tied to

a post like their cur dogs.

He

had no woman, children or family left.

His brothers died as warriors, faces painted, their weapons in

hand.

Their mother died long ago and

their father ended his life an old man, sad to see the last of the once-great

buffalo herds.

Pea’hocso

might still have a sister somewhere, but he didn’t know if she lived or had

died.

His wife, Aiyana

,

died giving birth to his third son and

the child followed her in death.

Pea’hocso’s

boys had defended their village from blue coats

at McClellan Creek.

One died there, the

other of smallpox at Fort Concho far from home.

Two of his daughters died of some fever, one in his arms.

Other

Comanche had all yielded with the Medicine Lodge Treaty, after the war that

divided the white men against each other––but not the

Quohada

.

They’d fought the buffalo soldiers, the

white men with black skins, across the plains for two full seasons but were

ordered to go to the place called ‘reservation’.

While other Comanche donned the calico shirts

and heavy pants white settlers wore, took up the plows and learned to speak the

white tongue, the

Quohada

rebelled.

They returned to the open plains and lived

free, joined by other Cheyenne warriors and renegades.

Time defeated them, along with the ceaseless

trek of the white faces into the

Comancheria

.

If the

ta’siwoo

hadn’t been slaughtered

for their hides and tongues, the Comanche people might’ve survived.

But the buffalo provided all to the people:

food, shelter, clothing, tools, and life.

Without them, their existence would end.

Hearts like the one deep within

Pea’hocso’s

chest refused to accept the reality and

struggled, but now he knew the time of the Comanche was no more.

Their

horses were put into a corral with Army livestock.

Pea’hocso

watched,

silent.

He said nothing when they filed

into a barracks building to spend the night.

The taste of the beans, brought in the kettles, was strange upon his

tongue and he didn’t care for the hard baked rounds called biscuits.

Hunger forced him to eat, but the strange

food wasn’t what he’d choose.

Nor were

the close quarters where odors of sweat and stench rose into his nose with

force.

He preferred fresh air and

solitude, and so he wrapped his blanket around his shoulders and walked

outside.

No one stopped him.

Pea’hocso

wandered away from the barracks

and felt better.

He stared upward at the

clearing sky.

Clouds scudded away to

reveal the full moon: the one Texans called the Comanche moon, reminiscent of a

time when warriors had prowled and raided.

A

powerful longing rose up within

Pea’hocso’s

soul to

slip into the night and let his stallion gallop across the open country.

He ached to go into battle, to take horses or

plunder.

Pea’hocso’s

skin prickled with blood lust.

If he

could hunt buffalo, he wouldn’t want to kill … but with few

ta’siwoo

left, he desired revenge.

Pea’hocso

might’ve vanished into the humid

night.

He could’ve taken his mount from

the corrals and bolted.

And if not for

the woman, he would’ve done so.

His calf

muscles tensed, and his body stiffened in preparation to launch in flight, when

she spoke.

“Good

evening.” Her voice carried the same kind of deepness as the blooming

honeysuckle he smelled nearby.

Although

he understood a great deal of English,

Pea’hocso

preferred not to soil his tongue with it or use the translation of his name,

Big Eagle.

He turned to see who spoke,

expecting a white woman in bonnet and shawl.

Her skin gleamed pale in the darkness, but she wore neither hat nor

bonnet.

Hair black as midnight streamed

over her shoulders and down her back with abandon and he stared, struck by the

sight.

Comanche women often kept their

locks short for ease, unlike the men, who let their hair grow.

She gazed back at him, from eyes deep blue as

a lake beneath a summer sky. “This is a wild place, isn’t it? But then you’re

wild, too.”