The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (24 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

You learned a little bit about Roman governance in Chapter 5, “Seven Hills and One Big Sewer: Rome Becomes a City.” Let's put it together here. Before we do, however, remember that no matter what the structure was, the Romans still operated like Romans: They deferred to authority, preserved precedent, and operated within their family and patron-client bonds. Their leaders, no matter who they were, strove for similar values as well: They sought to increase their

auctoritas

and

dignitas

and to win

gloria

for themselves, their family, and Rome.

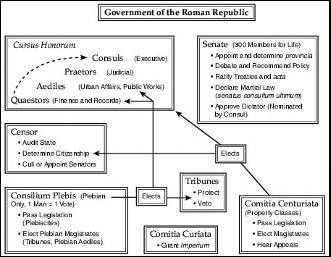

There were four Roman political bodies coming from different periods of Roman history and serving various functions:

- Comitia curiata

(ward assembly).

This was the oldest assembly of the Romans dating from the time of the kings. All citizens who could bear arms were members, but they were organized into

curiae

(wards), which seem to have originated in the early settlements of Rome. Each

curia

voted as a block. Its major duties included witnessing and approving the king and (later) other magistrates (such as consuls and praetors) who had

imperium

(the power of command). The assembly ceased to function for all practical purposes in the early Republic, though it continued to perform ceremonial functions and to grant

imperium

. - Comitia centuriata

(centuriate assembly).

This assembly was created by the kings, organized originally by fighting units of 100 men (hence, a “centuriate” organization). It developed into the general assembly in the Republic, electing magistrates and hearing appeals. The centuries were organized according to property classification, and the classes voted as a block. Unfortunately for the lower classes, the voting was such that if the two richest property classes voted in agreement (which they often did), the vote was decided. - Concilium plebis

(plebeian assembly).

This was the assembly that the plebs set up for themselves as a part of their succession in the “Conflict of the Orders.” Only plebeians participated although patricians often influenced it through its ties with the wealthy plebeians and the tribunes. Occasionally, a patrician had himself adopted by a pleb to become eligible. The

comitia plebis

operated on the principle of “one man, one vote.” It passed legislation, called

plebescita

(plebiscites), and elected officials (aediles) and their powerful representatives, the tribunes. The validity of plebiscites waxed and waned through the Republic depending on the strength of the senatorial party and the cohesion of the

nobiles. - Senatus

(Senate).

The Senate was originally made up of the

patres,

the aristocratic clan leaders who advised the king and from among whom the king was elected. By the time of the Republic, the number of senators was fixed at 300 at which it remained until Sulla (80

B

.

C

.

E

.) (see Chapter 7 for more about Sulla). The Senate was Rome's deliberated body: It formed policy, approved legislation passed in the assembly, passed decrees, ratified treaties, and appointed magistrates to provinces or to promagisterial duties. It could also, through the final decree of the senate (

senatus consultum ultimum

), impose a condition of martial law. During the last half of the Republic, a few powerful and influential families dominated the senate and the office of consul. This was, in part, what forced other nobles and aristocrats to turn to the popular assemblies and to violence in an attempt to advance their own ambitions.

Roman Magistrates

Â

Roamin' the Romans

Wherever you are in the Roman world, when you find a forum (public square and marketplace), you've found the heart of the political city. There were several fora in Rome, but the Forum Romanum was the most important. It was the political, commercial, religious, and social hub of the city. The

comitia tributa

joined the Forum in 145

B

.

C

.

E

., and the construction of basilicas to house public business and law courts began soon after. Other important public buildings included the

Curia

(Senate House) and

Rostra

(speaker's platform).

Most Roman magistrates were elected by the assemblies and served for a term of one year. Some officials, like dictator, pro-praetors, and pro-consuls, were appointed and could have flexible terms. Most, if not all, had age minimums after 180

B

.

C

.

E

. although in the later Republic such minimums were overlooked for young men such as Pompey the Great. Here's a list, beginning at the bottom of the political pecking order:

- Quaestors

were public finance and record officials (roughly a Purser or Treasurer). They had to be at least 25 years old. - Aediles

were in charge of urban affairs including weights and measurements, public works, public games, and public safety (a bit like a county Auditor). They had to be at least 36 years old. - Praetors

were second to consuls. They were primarily judicial officials (judges) and could have the power of

imperium.

They had to be at least 39 years old. - Consuls

were the chief executive officials of Rome. They commanded the army, handled national and foreign affairs, and possessed

imperium.

The American President is modeled on this office. Consuls were supposed to be at least 42 years old. Romans passed different laws on their ability to be reelected; at first there was a required 10-year span between elections and then, in 150

B

.

C

.

E

., a ban on reelection. As Marius, Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar all demonstrate, this ban didn't hold. - Censors

were elected every four or five years. They did not have

imperium

but had other powers that made them eventually one of the most influential officials. They possessed the power of enrolling citizens in the proper tax and military rolls and acted as auditors of public expenditures. They could also remove members of the senate for immoral behavior. - Dictators

(a supreme commander) were nominated by a consul and approved by the senate for a set period of time. The dictator was the chief official under a state of emergency and military law. He had complete control of all civil and military affairs. - Pro-praetors and pro-consuls

were

ad hoc

praetors and consuls who were appointed by the senate to act in the place of a praetor or consul for a specific assignment. These offices became a common way for Rome to meet the military and administrative needs of its growing empire.The basics of Roman Republican Government.

Cursus Honorum

Young aristocrats sought to follow a career path from quaestor to consul that was, in fact, called the “path of offices,” or the

cursus honorum.

After 180

B

.

C

.

E

., minimum ages and a two-year interval between offices were legalized. The final stages of this path became monopolized, as we've said, by an increasingly smaller number of families over time even as the rewardsâand costsâof achieving office grew. This led, in campaigning, to wildly competing expenditures and campaign practices. Romans passed a series of campaign laws (none of which worked) to cut back on them. It also

led ambitious Romans, when blocked, to exploit the tribal assemblies and to bring their clients, political gangs, and (finally) armies onto the political landscape (see Chapter 7).

Roman law,

ius,

and the handling of laws,

leges,

are one of the Romans' most enduring achievements. Important developments in Roman legal history took place during the Republic; these were refined during the Empire and finally codified and published under the emperor Justinian in

C

.

E

. 540. Justinian's

Corpus Iuris Civilis

(The Body of Civil Law) encompassed over a thousand years of Roman legal history and remains an integral part of western European law. The Romans divided their law into public and private. Public law applied to affairs of the state, private to the affairs of individuals. We'll concern ourselves with private law here.

Â

Veto!

Whereas western European and international law is indebted to the Romans, United States law is not; it depends more on the traditions of Anglo-Saxon law passed down from Britain.

Before the Twelve Tables (450

B

.

C

.

E

.), law was in the hands of the aristocratic patricians and priests (also patricians) who oversaw the rigid formulas that had to be precisely followed and witnessed before their authority. Legal questions concerning the rigid interpretation of what was said in the formulas was theirs as well. But after the publication of the Twelve Tables, affairs began to change. Roman interactions among themselves and with other people became more complex. Judges were required to gauge intent and to render decisions based on the case and measured against a partially recorded tradition. Over time, the judgments and proclamations of these judges became a body of tradition in and of itself.

The state did not bring either civil or criminal cases; there was no “

the state vs.

_______.” All prosecutions were brought by private individuals; plaintiffs personally brought defendants before presiding magistrates (sometimes defendants who were dodging court had to be physically dragged!) to prosecute their case. Plaintiffs were required to speak for themselves unless they were women or children. Prosecutors could, however, bring in secondary speakers. Defendants could defend themselves and/or have others speak in their defenseâhopefully people whose

dignitas

and

auctoritas

the jurors recognized. Having patrons or talented clients was an asset. Cicero came to prominence representing clients both Roman and foreign.

Court was a different affair back then. At first, criminal trials were held before the assembly under a praetor. Later, standing juries (

quaestiones perpetuae

) were set up under a praetor or an appointed judge (

iudex

). In civil cases, trials took place before a private judge (

unus iudex

) or, in major cases, before a jury of 100 (

centumviri

) presided over by a magistrate or learned jurist.

Plaintiffs brought their cases and defendants before the presiding magistrate. In civil cases, the magistrate would question the participants and might elicit a resolution to the case or determine that there was no grounds for trial. If there were grounds, he determined the exact nature of the charges and the legal question to be considered and sent his instructions to a judge (

iudex

) or a jury (in important cases) for consideration.

The rendering of opinions by the magistrates referring cases to trial, the proclamations of the praetors, and the decisions of the judges were law. But by the third century

B

.

C

.

E

., such decisions had begun to acquire a tradition of their own. Influential Romans, such as the first plebeian

pontifex maximus

(high priest of Rome), began giving legal advice to bolster their political support. Opinions of jurists became a part of the mix as well: In 204

B

.

C

.

E

., Aelius Catus published a legal commentary on the law of the Twelve Tables as it had developed. Romans, in keeping with their tendency to base the future upon the past, looked to precedent (literally, what “goes on before”) against which new decisions could be made, and from which decisions could be applied to new situations.

Â

Lend Me Your Ears

The poet Horace was saved from an unwanted tag-along in the Forum:“By chance we met someone who had a suit against him. âAnd where are you going, you wretch?' he cried and turned to me. âCan you be a witness for me?' he asked. I assented and he snatched him off to court, thank god.”

âHorace,

Satires

1.9

Â

Veto!

Romans may have valued precedent, but they were not legally bound by it. Neither civil nor criminal law was codified; decisions were at the sole discretion of judge and/or jury.