The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (60 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

It's good to keep in mind that the spectator culture of Rome was just thatâRomans watched but for the most part did not participate. There weren't permanent sites for entertainment, with the exception of the Circus Maximus, until the late Republic and early Empire. Festivals and the entertainment that went with them were transitory affairs, and Romans looked upon the performers, whether they were actors, dancers, and musicians, as carnies.

Being a charioteer or gladiator was the work of slaves. No good Roman would stoop to appear on stage or compete, like the Greeks, in competitions such as the Olympics. Such exhibition was not only silly, but it had no practical application to work, politics, and conquest that Romans engaged in. This is why Nero's appearances on the stage, Commodus's ambition to be Rome's main attraction, and the occasional appearances of noble Romans (including women) in the arena shocked the upper classes and titillated

the common folk. Those nobles and emperors might as well have played a saxophone on late night television, publicly enjoyed pork rinds at a Texas BBQ, or been a part of WWF wrestling matches.

The ancient world had a history of public entertainment and competition connected with holidays and festivals. The competitive performance of Greek tragedy and comedy in Athens is a famous example, the Olympic games are another. Sacred holidays or occasions also involved parades, dances, and both solemn and carnival-like public activities. Two of the most famous examples are the portrayal of the

Panathenaic

procession on the frieze of the Parthenon in Athens (the Elgin Marbles of the British Museum) and the reliefs of the

ara pacis

of Augustus in Rome.

Â

When in Rome

The

Panathenaic

festival was a yearly civic and religious festival held in Athens in honor of the city's patron goddess, Athena.

The major festivals of Rome were based in religious celebrations of the early Republic, but came (like in our own day) to be more “holidays” than “holy-days.” Not all holidays included

ludi

. By the time of Sulla, there were six major Roman religious festivals (57 days) that included

ludi;

other towns and cities would have had approximately the same schedule. Festivals that did have

ludi

usually had several days of performances culminating in a day of big-ticket games (races, hunts, or gladiatorial combat). Here are the major Roman state games:

- Ludi Megalenses

(April 4â10) celebrated the arrival in Rome of the cult and sacred stone of Cybele in 204

B

.

C

.

E

. - Ludi Cereales

(April 12â19) were celebrations of Ceres, the goddess of grain. - Ludi Florales

(April 28âMay 3) were festive celebrations of Flora, an ancient Roman goddess of flowers and fertility. - Ludi Apollinares

(July 6â13) were dedicated to Apollo from the time of the Second Punic War in thanks for his help. - Ludi Romani

(September 5â9) was an ancient celebration that occurred in thanks to Juno, Jupiter, and Minerva (Athena) at the end of the military campaigning season. This was one of the first festivals to which dramatic performances were added. - Ludi Plebii

(November 4â17) were apparently an early plebeian version of the patrician

Ludi Romani.

In the first century

B

.

C

.

E

., generals such as Sulla, Pompey, Caesar, and Octavian began to celebrate their own victories with holidays (like our modern V-E Day) and games

funded by their conquests. Special games, such as the

Ludi Saeculares

which gave thanks for the end of a long period (

saecula

), could also occur. Under the Empire, games were also instituted to commemorate emperors' birthdays (like our Presidents' Day). By the fourth century

C

.

E

., Romans could enjoy

ludi

177 days of the year.

During the Roman Republic, the aediles (officials in charge of urban affairs) oversaw public funding and production of

ludi.

Ambitious politicians, such as Julius Caesar, used their own revenues or borrowed heavily to win public favor by adding to the public funds to create spectacular games. Gladiators weren't a part of the publicly funded entertainment until late in the Republic (more on that later). Instead, public events included dramatic performances (such as comedies, tragedies, pantomimes, and rustic farces), staged hunts, animal exhibitions, and the biggest event: chariot races.

During the Empire, gladiatorial fights were added and shows of all kinds got bigger, bloodier, and more elaborate. These shows became a staple all over the Empire for urban populations that, in Juvenal's words, demanded their

panem et circenses

(bread and circuses).

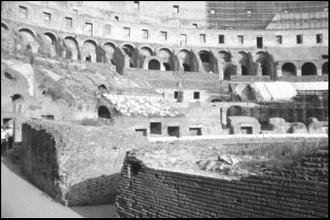

The interior of the Colosseum, with the vestal virgins' box seats (center).

Chariot racing was the big event of ancient spectator sports and went way back before the Romans: The Olympic and other Greek games featured wealthy aristocrats from all over the Hellenic world competing at the “sport of kings.”

By the time of the Romans, chariot racing was a for-profit operation. Four teams, the Reds, Blues, Whites, and Greens, competed all over the Empire, a bit like Team Porsche and Team Ford do in professional car racing. These teams were run by wealthy owners just as professional teams are today. It took a lot of money to breed, maintain, and train champion horses, and have a supply of chariots and drivers.

Before the

ludi,

the aedile or public official in charge of setting up the race entered into negotiations with the four teams to rent horses, drivers, and support teams for the period of the games. Officials tried to get top-notch teams of drivers and horses for their events. Teams received a negotiated fee for participating and then any purse money they won. Purses ranged in amounts, but big ones ranged between 40,000 and 60,000 sesterces.

On the day of the race, crowds crammed into bleacher-style seats. You know how some guy or family will hog bleacher space by spreading out their stuff on either side of them? No such thing allowed in Rome. The rule was that you had to be touching your neighbor; this allowed as many as possible to get in. The poet Ovid points out that this made for a great way to meet girls. Here is a quote from his

Art Amatoria

(1.134â162) in which he describes seduction strategy in the Circus:

Don't let the contest of the noble chariots escape your notice; a racetrack full of people offers many opportunities. You don't need to communicate secrets with finger-talk or make do with a nod and a glance, just sit right next to your heartthrob, no problem, touching and joined at the hip by the narrowness and regulation of the seats!

Start conversation in the usual friendly way, and let what's being said around you get you started. Ask the girl eagerly whose horses are running that day and don't hesitate, whoever it is, to be for the same as she is! Then, when the statues of the gods are brought in, be sure to clap loudest for Venus, the Goddess of Love.

Now, if by chance a little bit of dust falls into the girl's lapâOh! It simply

must

be bushed off with your fingers. And if there's no dust . . . brush it off anyway. Any excuse to get involved warrants your attention. . . . The Circus presents these openings to new love.

Races featured two-, four-, or sometimes even six-horse chariots, depending upon the event. Numbers of chariots in the race depended on the size of the venue; the Circus Maximus could run up to twelve four-horse chariots. In the Circus Maximus, races lasted for seven laps (about two and a half miles). A long low wall down the center kept chariots from cutting corners, and terminated in a turning post at each end. Chariots and horses lined up against a starting gate with grooms to help hold them in position. At the signal (a blast from a horn), the chariots flew down the stretch with the drivers leaning forward over the front of the chariots, whipping the horses, and bracing for turns.

Racing chariots were like skateboards hitched to horses: small, light frameworks with wheels about the size of a wheelchair and a platform just big enough for the driver to stand on. Racing was an all-out contact sport. Drivers jockeyed for position and rammed each other out of the way. Knowing how to navigate the turns was crucial to staying in the raceâand staying alive. Crashes were frequent, and frequently fatal.

Chariot drivers began as slaves or the children of drivers. Even though the owners won the purse money, some of it must have gone to the drivers because winning drivers were able to purchase their freedom (if they lived that long). Still, winning one race paid as much as a schoolmaster earned in a year, and winning drivers became celebrities. A big-name driver could scarcely go out in public without being mobbed by women and men. One of the most famous, a late first-century charioteer by the name of Scorpus, appears in several of the poet Martial's poems. Scorpus won an amazing 2,048 victories and died in a crash at the age of 26. Martial (in two other poems) and Scorpus's fans mourned him after his death just as modern fans mourned the loss of NASCAR racing legend Dale Earnhardt.

Supporters from all levels of society cheered the colors of their favorite teams. When the race began, crowds leapt to their feet and began cheering and waving banners and togas. If there was a false start, people shouted and waved their togas for the race to begin again. Can you imagine this with up to 250,000 fans at the Circus Maximus? It must have been wild. Groups of supporters were called

factiones

(gangs). Besides cheering on their team, chariot hooligans traded insults and fought before, during, and after the races. In Constantinople, the factions became so powerful and dangerous that they nearly toppled the emperor Justinian.

The other major attraction of the games were exhibitions that featured life and death struggles.

It's important to distinguish what kinds of people killed each other in the Roman games: They were either criminals or professional gladiators. Convicted criminals were fed to the beasts or were forced to kill each other by pitting an unarmed man against an armed one. After each death, the victor was disarmed and faced the next armed opponent. This kind of carnage was lunchtime fare (

meridianum spectaculum

) before the battles of the professionally trained fighters in the afternoonâthe gladiators.

The spectacle of gladiatorial combat originated in Etruria as a part of aristocratic funeral games and sacrifices. For this reason the matches were known as

munera

(obligations to the dead) rather than

ludi.

They were introduced into the Roman aristocracy in the mid third century

B

.

C

.

E

. They were privately funded events and became a way for aristocrats to develop popularity and prestige. By the first century

B

.

C

.

E

., Caesar's lavish use of gladiators and the revolt of Spartacus show that gladiatorial combat had become a popular and lucrative spectator event. Augustus and the emperors exploited the mass popularity of the games and gladiators by offering games in

their own names. These games were an important part of the emperors' public relations.

Arena spectacles and executions followed wherever Romans established themselves, and although they were protested by some, executions and gladiatorial fights became a successful popular export of Roman mass culture.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Athletic games and contests were a part of the aristocratic funeral celebrations in the ancient Mediterranean. If you've read the

Iliad

or the

Aeneid,

you know about this. The Olympic Games, in fact, were by tradition the funeral games of the hero Pelops. Julius Caesar put on games to honor the death of his daughter, Julia.

Gladiatorial contests were originally held, like the

ludi,

in temporary venues in the markets or forums with fights between only a few pairs of gladiators. In spectacles, however, bigger is better. Caesar featured many pairs of gladiators sparing off against each other at one time; in Augustus's games, 5,000 pairs of gladiators fought over the course of the games, and 5,000 fought in Trajan's games over the course of a month. Venues also became professional: the most famous, of course, is the Colosseum.

The entrance to the Roman arena in Nîmes, France.

The cost for these kinds of games was enormous and could be afforded only by the emperor. Smaller games outside of Rome might be put on by local magistrates or officials, but for anything of size, permission (and perhaps funding) had to come from Rome.

Gladiators came from slaves, war captives, and criminals. Men were sold to a gladiatorial school under the supervision of a trainer (

lanista

) and the owner. Yes, sometimes free men in desperate circumstances entered the schools on their own. If so, they had to swear an oath of complete submission to be enrolled in the

familia

of the school. Once they agreed “to be burned, to be bound, to be beaten and to be killed by the sword,” they were trained and hired out to games three or four times a year. Most gladiators died in the arena fighting beasts or members of their own

familia.

The talented, however, could hope to win their freedom and the honorific wooden training sword that gladiators were presented with at their retirement. Retired gladiators sometimes returned to the schools as trainers/coaches or hired out as private bodyguards.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

You'll find the remains of a gladiatorial school and barracks in Pompeii, where the first permanent amphitheater was built.

Top gladiators were, like top chariot drivers, objects of public adoration. Inscriptions in Pompeii record how certain fighters made girls swoon, and Juvenal (in

Satire 6: Against Women

) tells us about Eppia, the wife of a senator who ran off with a gladiator to Alexandria and joined his school (I'll bet you wouldn't want to get between those two in a spat!). Fighters in the Thracian style (see the following section, “Specialists”), who wore the least clothing, were apparently especially popular with women. From funerary monuments, it appears that many gladiators took a grim pride in their profession, combining a measure of fatalism with a sense of duty that often accompanies public figures whoâin one way or anotherâsacrifice themselves to the desires of “their” public.

Originally, gladiators were captive warriors and fought each other with the equipment they had. Since they came from different backgrounds, they fought with an exotic array of arms. As the sport became more professional, a variety of fighting styles and equipment emerged and gladiators specialized to match their bodies and abilities. Matches pitted different types of fighters against each other to make them more interesting by balancing strengths and weaknesses.

At the bottom of the food chain, so to speak, were the

bestiarii,

who fought for their lives against wild animals. These men were rarely armed with more than a whip or a spear and some leather protective clothing.

Venatores

were specialists in the hunts (

venationes

) that obliterated so many animals from around the Empire. It's not clear if trained gladiators or simply condemned captives fought in the staged naval battles (

naumachiae

) that occurred in the Colosseum or artificial lakes flooded for the games.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Gladiators lived in a highly regimented and disciplined hierarchy. Owners (or imperial managers) of gladiatorial schools took great pride in providing the best in facilities and specialist trainers. Besides living quarters, facilities featured places for fans to watch gladiators train (like spring training facilities). Owners also took good medical care of their valuable investments, retaining on staff both physicians and dieticians who were often first-rate professionals. The famous physician Galen (Marcus Aurelius's doctor) began in a gladiatorial school and was proud of his reduction of its mortality rate.

At the top of the ranks were the highly trained and specialized fighters. There were many kinds and tended to be named either for the country of their fighting style's origin or for the distinctive weapon they used. Generally, however, they can be broken down into two groups: fighters who relied on strength and armor, and those who relied on speed and mobility.

Heavily armed fighters included . . .

- Secutores

(pursuers in the Samnite Style). Secutores were armed with a large shield, a sword, a heavy simple helmet with eyeholes, one protective arm sleeve, and a protective greave for their forward leg. They were originally called Samnites, but after the Samnites became allies and Romans, this name was dropped (an early example of PC language change?) and the name “pursuers” was adopted, probably because they had to pursue the more lightly armed fighters who relied on mobility. - Thraeces

(Thracian-style). Thraeces had a helmet with a wide brim, crest, and protective visor. They were armed with a scimitar (curved sword) and small shield and wore greaves on both legs. - Myrmillones

(Gallic-Style). Myrmillones were heavily armed fighters who were named for an emblem of a fish on their helmets.

Lightly armed fighters relied on speed, mobility, and trickery to defeat their opponents. They included . . .

- Retiarii.

The Retiarii were armed with only a net and a tether to ensnare their opponents and a trident to strike from a distance. Their only defensive armor was a shoulder piece to protect their net arm. - Laquearii.

These fighters used a lasso. - Sagittarii.

The Sagittarii were armed with bow and arrows. - Essedarii.

Essedarii fought from Celtic war chariots (probably introduced by Caesar's conquest of Britain). - Dimachaeri.

These gladiators fought with two swords.

Some gladiators apparently fought with highly specialized weapons or armor. We don't know too much about them, but their names make you think as much of the movies featuring Mad Max or Luke Skywalker as they do of Romans. Three of them were . . .

- Scissores.

Scissores were gladiators whose name means “carvers” or perhaps “slicers and dicers.” - Provocatores.

Provocatores means “challengers” and refers to the calling of an enemy out to fight. No one knows what this means, but since gladiatorial pairs were drawn by lots, I've wondered if this might indicate some kind of challenge bouts where gladiators could challenge specific opponents (sort of like challenging the heavyweight for the title). - Andabatae.

These were gladiators whose helmets blocked their vision so that they had to fight opponents blindly. Can't you hear the

lanista

(trainer): “

Utere illa vi, Luce

” (Use the force, Lucus)?

As gladiatorial combat became more a spectator spectacle than a solemn funeral rite, the Roman spectators' desire to see the bizarre and strange, as well as the fans' fantasy of participation, affected the games. Both dwarf and female gladiators (Amazones) are mentioned as a part of the games of Nero, Domitian, and Commodus. Female gladiators were especially popular, and although there couldn't have been many, they appear to have been a fairly regular part of the top entertainment bills. The emperor Diocletian spoiled the fun in 200 and banned women from the arena. Dwarfs, however, apparently still continued to be a part of the games.