The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (66 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Conflicts between church and state took, in the words of the singer-songwriter Warren Zevon, “lawyers, guns, and money.” The popes and the Holy Roman Emperors had the medieval equivalent of the last two, but a few hundred years' lack of legal scholarship had left competent lawyers, amazingly, in short supply. This led to the resurrection of the study of both canon and Roman law codes among scholars in such centers as Bologna (eleventh century) and Naples (1212). The law schools in these cities grew into important medieval universities.

Onward Christian Soldier

Â

When in Rome

The

crusades

were holy wars (particularly of the eleventh through thirteenth centuries) in which Christians from Europe attempted to conquer territories (especially in the Middle East) that were held by Muslims or people holding beliefs that the crusaders considered heretical.

As we've seen, the conquest under the banner of one god or the other has a long tradition. The eleventh through fifteenth centuries saw a variety of

crusades

to recapture lands for Christendom. Although you're probably most familiar with those to reconquer the Holy Lands, crusades for other territories, such as Muslim Spain, were also launched. The crusades began with an appeal from the Byzantine emperor Alexius Comnenus (father of the historian Anna Comnena) to Pope Gregory VII and Urban II

for help against the Turks. What Alexius got was not what he, or probably the pope, expected. Here's a chronology of some of the crusades that followed in the next centuries:

- First Crusade

(1095). Pope Urban II called for this crusade and promised crusaders who died in battle the “immediate remission of sins.” - People's Crusade

(1096). While the nobles assembled an army, peasants and poor knights marched off fervently to take the Holy Land. They massacred Jews in Germany along the way and were massacred in turn by the Turks near Antioch.(1099). The better prepared army of nobles of the First Crusade reached the Holy Land, captured Jerusalem, and butchered its inhabitants. In 1144, a Muslim counter-crusade under Zengi retook the Crusader state of Edessa.

- Second Crusade

(1147). In response the to the capture of Edessa, Pope Eugene II called for a crusade. This crusade ended in dismal failure and emboldened the Moslem states in their resistance to the Latins. - Third Crusade

(1189). Under Richard the Lion Heart, King Philip II of France, and the Holy Roman Emperor Fredrick, Barbarossa recaptured most of the Crusader states except Jerusalem. - Fourth Crusade

(1204). This campaign captured Constantinople and did serious damage to the Byzantine Empire (and its relations with the west). - Children's Crusade

(1212). Rallied by youth preachers in France and Germany, thousands of boys as young as six years old joined the march to the Holy Land. Many died en route, and those who reached Marseilles found that the sea didn't part for them as promised. Undaunted, the remainder set sail. Some died in shipwrecks, and the rest landed in Egypt instead of Palestine and were sold as slaves. Few returned to their homes. - Fifth Crusade

(1219). Preached by Pope Honorius III, this crusade set off to capture Jerusalem, but with this city so strongly defended by the Muslims, decided to try and conquer Egypt instead. Their attempt almost succeeded but bogged down at the city of Damietta, where internal dissention and bad leadership cost the crusaders Jerusalem and the Muslim's offer to return the True Cross, which then disappeared from history. - Sixth Crusade

(1228). The Muslim capture of Jerusalem in 1189 ignited great passions in Europe. The Holy Roman emperor Fredrick II recaptured the city in 1229, but he alienated the other crusader leaders and the pope. - Seventh Crusade

(1249). This Crusade was led by King Louis IX (St. Louis) of France, who had vowed to undertake it against the Muslims if he recovered from a serious illness. This crusade became great literature (such as the romanticized and chivalrous memoirs published between 1304 and 1309 by Louis's close advisor, Jean sire de Joinville) but failed to achieve its objectives. St. Louis and his army were captured by the Moslims in Egypt. He was ransomed and eventually returned to France.

The Holy Roman Empire continued in one form or the other up through Napoleon. Despite the name, it wasn't holy, Roman, or (if you research it) much of an empire most of the time. Nevertheless, Rome's name and legacy continue to be invoked for either reclaiming or establishing empires or republics. The empires of France, Britain, Russia, Spain, the Ottomans, and America have elicited comparisons intended as both praise and blame. As you can imagine, the legacy of imperialism and colonialism has shifted most toward the latter. Nevertheless, even current discussions of the European Union have brought Rome's legacy back as a historical shadow, along with all the possibilities, baggage, and barnacles that have adhered to it along the way.

Recent empires could hardly help but compare themselves to their Roman ancestors one way or the other. The Spaniards, in their conquest of the Americas in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, had an ambivalent attitude toward their Roman past. On the one hand, the Spanish had contributed greatly to Rome: Both Roman poets and emperors had come from Spain. On the other, the Spanish wanted to distinguish themselves in their own terms against other Europeans who had claim to the Roman legacy. The Spanish liked to portray their ancestors as being brutally subjugated by the Romans, but as having escaped that yoke to become the rulers of an even greater empire. Some Spanish missionaries, however, turned this argument on its head and maintained that the Spanish were in fact replicating Roman actions and attitudes in their brutal conquests, and warned that these would lead, as they had with Rome, to a Spanish fall.

Even though Napoleon put an end to the Holy Roman Empire in the treaty of Luneville (1801), that didn't stop him from playing off France's links with the Roman past. Like many great commanders, he appears to have personally favored Alexander the Great. But in becoming emperor of France (1804), Napoleon attempted to have the pope crown him as he had crowned Charlemagne and the Holy Roman emperors. Napoleon, however, had to take the crown from the pope and crown himself at the last minute. (Perhaps the pope was waiting for him to stand up?)

Â

Roamin' the Romans

Napoleon, like many other European rulers, sought to emulate Roman grandeur and power in public architecture (French Empire style). The most famous example of this is the Arc de Triomphe through which he intended to march his army. He never got the chance, and it served as a bitter irony that Hitler was the first to use it.

Even the British played with comparisons to Romans, but like the Spanish, the British have had an ambivalent relationship with Rome. (Both are proud of having been a part of the Empire just as long as everyone bears in mind that they didn't become a part willingly and were hard to conquer.) Conquest from the continent was never something to validate. Closer to our own day, Hitler and Mussolini (Fascists, from

fasces,

the Roman symbol for authority) borrowed from Roman grandeur and promoted themselves and their conquests as new

Reichs

(reich means empire or kingdom) and Romes.

Americans have their own Roman past, which anyone can read about in the works of the founders of the “Republic.” Federalists like John Adams championed the idea of a state anchored by a strong executive and bicameral (having two legislative chambers) senate. Rome's legacy of tyranny was an uncomfortable subject, however, and so most of the references to Rome come from Rome's Republican past. Cicero, Livy, and Seneca feature heavily in the classical references penned during the lively correspondence leading to the formation of the United States Constitution. Democrats such as Jefferson championed more individualistic traditions, but in the end, the framers rested the American state solidly on a Roman foundation. That's why you'll find many statues of George Washington (who idealized Cato and Cincinnatus) and other framers wearing Roman togas, not Greek or Anglo-Saxon tunics.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

You probably have heard of the Third Reich of Nazi Germany under Adolph Hitler, but where did the other two Reichs go? The First Reich was the Holy Roman Empire, which came to Germany from Charlemagne through Otto I. This Reich lasted until Napoleon defeated the forces of the last Holy Roman emperor, Francis II (1768â1806). The Second Reich was founded by the first Imperial Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck (1815â1898) in 1871. WWI ended this Reich, and WWII ended the third.

You're a Roman, Too

I said at the beginning of this book that whether you love them or hate them, there's no getting around the Romans. A sizable part of contemporary culture is wrapped around a Roman core. It's true that what was originally Roman has often changed and mutated to such a degree that it would be as unrecognizable to them as Manhattan Man would be to Lucy

Australopithecus

. But this is the nature of western classicism in which each generation finds (or even mistakes) something anew in its tradition and reinvents the past in its own image.

Nevertheless, so much of our tradition has been invented by, funneled through, or made in reaction to the Romans that they are culturally genetic to the west. While it's been impossible to create a complete “Roman genome project” in this (or any) book, I hope this one has helped you to better understand and appreciate some of Rome's fascinating story. I also hope that you'll want to unravel more of the story of Rome's evolving impact upon history while realizing that complexity and ambiguity are a part of the fruits of investigation.

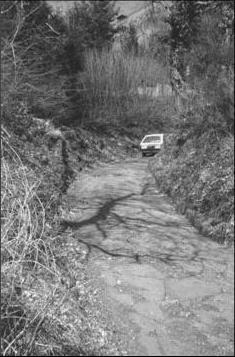

We may not always know where we're going, but, like this car, the modern world still often travels on ways laid down by the Romans.

It may be time, for example, to return to a consideration of Rome's legacy concerning the relationship between individual and community and the interrelation of communities to a larger structure. In an age of tensions between global “community” and fragmentation of communities into ever-smaller niches (sometimes only connected by electrons and emotion), the Romans are worth revisiting both for cautions and for inspiration.

Just as the Greeks have been used as a potent model for the pursuit of individual human achievement, the Romans are the west's communitarian models. They, more than any culture since their time, attempted to negotiate practical differences in class, ethnicity, religion, legal status, and culture under the aegis of a common view of human order. Their achievements over the centuries, as well as their deficiencies, bear investigation and consideration.

You already

comprehend

that many

intellectual concepts

and

traditions

were

created

or

survived

through

Rome.

But did you

realize

that you

communicate

in large

part

through dialects and

modes

of

Latin?

Although English is a Germanic

language,

it was heavily

influenced

by

French

(a

Latin derivative

) after the

invasions

of the Norman

Franks.

In

addition, Latin's influence

through

poetry, art, legal studies, sacred

and

secular literature

(

et cetera

) was so

profound

that

Latin

has both

inspired

and

infected

not only the

concepts,

but the very

terminology

that we use to

describe

and to

conceive

of our world. This

brief declaration provides

you a

minute picture

of how

pervasive Latin

is:

vocabulary

with

Latin origins

is

italicized.

The Romans were essentially optimistic. They generally operated as if they could control the future by the choices they made in the present.

Romans suffered from many of the deficiencies, as well as from the advantages, of such an outlook. Optimists are always disappointed (because if you would just make the right choice everything would be fine, wouldn't it?), and the Romans were prone to blaming or doomsaying when things were not going their way. They tended to feel overly responsible to the god or gods that put them in charge of history. They often suffered the arrogance of thinking that they knew what was best for everyone, that they had everything under control, and that they could always figure it all out. Generally adverse to theory, they preferred the practical, the tried, and the real world of real life in Roman terms.

The Romans were, on the other hand, willing to take on the largest of challenges, persevere to the end of endeavors, and to doggedly insist that there was indeed no no-win scenario if one would just figure out how to go about things properly. Their history and legacy give good evidence that there was, indeed, something to it.

Â

Veto!

Of course, you can't press an analogy between U.S. and Roman cultural attitudes to their historical role too far. Still, when you consider Jupiter's proclamation for Rome in Virgil's

Aeneid

(“For these people I place no boundaries of space or time: I have given them empire without end”) and John O'Sullivan's

Manifest Destiny

(“The far-reaching, the boundless future will be the era of American greatness. In its magnificent domain of space and time, the nation of many nations is destined to manifest to mankind the excellence of divine principles”), it gives you pause.

At the risk of making overly broad proclamations, people living in the United States can learn a lot about U.S. political history from a consideration of Rome. The United States has a remarkably Roman attitude toward its place in history, progress, and the possibilities of the future. (It's probably not an accident that the United States' major contribution to the philosophical tradition is pragmatism, with its emphasis on practical results rather than on theory.) In looking back over the long history of U.S. traditions, citizens of the United States (and other Romans) might come to a better understanding of where we are, how we got here, and where we can go.

- The legacy of Rome continued to influence empires and imperial ambitions from Charlemagne to the Third Reich.

- The growth of papal power was rooted in filling spiritual and physical needs of central Italy in the fifth and sixth centuries and grew through an alliance with the Franks.

- European and American languages, history, and thought have been indelibly marked by the legacy of Latin and Rome.

- The study of Roman history and culture still has a lot to offer a multicultural and global world.