The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler (14 page)

Read The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Reggie Oliver

I could see the fear in his eyes when he saw me. He knew that I had found him out, but he made a very adequate pretence of seeming unconcerned. After he had signed my book he handed me a card.

‘Here’s my number. Give me a call some time. Let’s have a drink.’

I have to admit, I had no idea what his game was. Perhaps he saw this as an opportunity to finish me off, drain the last ounce of energy and success out of me. How, I was not sure. That I discovered later. As far as I was concerned he had issued a challenge, and I must take it up. What he didn’t know, and what gave me the edge, was that I had been laying my plans for this meeting for weeks before. I rang him up the following day, said I would be passing Ebury Street on my way to the theatre round about a quarter to seven and could I take him up on his kind invitation?

Bentley was correct, of course, about all the superficial details, the mechanics if you like, of the killing. I respect Bentley as a professional; and I believe he respects me too, as a professional. But what he couldn’t know—or understand—was what happened between MacIver and me.

I arrived there at twenty to seven and he let me in. He was in a buoyant mood. He gave me a drink and started to ask me about my family. He seemed obsessed by the idea that our resemblance had some sort of genetic origin, but I knew this was just a blind. Well, we drew a blank on the ancestral front. We were not related, and we both knew that the explanation lay far deeper than that anyway. MacIver paused and smiled: the first skirmish was over.

‘I’m doing a Sunday Arts programme on self portraits,’ he said at last. ‘Perhaps we could use you. I can’t think how at the moment, but it’s an interesting idea.’ He led me towards the huge mirror he had over the fireplace. We stood side by side looking into it. I was marginally taller, I suppose, with perhaps a little more hair, but otherwise it was uncanny. Once or twice I found myself looking into my eyes and then realising that they were not my eyes but MacIver’s. That must have been a trick of his, to make me do that. He smiled, then he said: ‘Have you ever fantasised about having sex with yourself?’

I stayed calm, but it was a horrible moment. MacIver had planned to take the last drop of energy and spirit from me by means of the sexual act. My last vital fluids would be absorbed into him and he would be filled with my life. It was something finally to know his game. Swallowing my revulsion, I smiled at him.

‘It’s an intriguing idea,’ I said.

‘The charm of novelty,’ he replied. Our eyes locked in the mirror and again I had the odd sensation of looking at myself and then finding that it was him. He put his hand on my shoulder and with a friendly compelling movement pushed me through into the bedroom. When he took his jacket off I knew the moment which comes only once had arrived, so I took the knife out of my pocket and stabbed him to death.

Now they suspect me of murder. I don’t mind that because after all it’s true. Bentley is a smart man and I would have been disappointed if he hadn’t guessed. We both know that a jury cannot convict on an ingenious theory alone. I had been very careful not to leave fingerprints or other traces. I even took precautions at Harpo’s, though I must admit that that little trick of tapping the glass with my fingernail (which is my mannerism) was a mistake. The tricky thing will be the phone records. I still don’t know what the results of their enquiry have been. But if they’re bluffing, as I suspect, my position is still very strong, which means there will be a stalemate.

All the same, I am annoyed that they won’t believe me when I say I am being stalked. I

am

being stalked; it happens more and more; I can barely stir outside my flat without hearing the footsteps behind me, but they won’t believe me. I also know

who

is following me. I caught a glimpse of him in a shop window; and they

certainly

wouldn’t believe me if I told them who it is. I’m not afraid, though. He’s not a threat to me now that he’s dead, just a damned nuisance. The police should believe me and do something about it; that’s what they’re there for: to help the living, not the dead.

Aristotle said that one of the advantages of being thought a liar is that no-one believes you when you tell the truth. Of course, he was being ironic. (How the hell did I know that about Aristotle?)

**

Note by D.I. Bentley:

The above document was found on an encrypted computer file after a second, more extensive search of Soames’s flat. It was this which finally secured his conviction for the murder of MacIver. He received a life sentence because he refused to plead diminished responsibility. Oddly enough, though at the time I didn’t believe the story about his being followed, it did turn out to be true. I had put Soames under surveillance and D.S. Weyman, who is not given to imaginative flights, swears that he saw a man shadowing him on a number of occasions. What Weyman also swears is that Soames’s pursuer looked uncannily like Soames; and uncannily like MacIver for that matter. Weyman tried several times to apprehend the stalker, but failed. I leave readers of this file to draw their own conclusions.

During the trial some facts emerged about the origins of Soames and MacIver which could be of significance. They were twins and had been secretly adopted by two sets of parents. This had never been disclosed to them because the birth mother and father, as well as the surrogate parents, had all been members of a strange cultish commune called the House of the Moon which had broken up amid considerable scandal in the late 1960s. The true parents of Soames and MacIver could not be traced because they were only ever known by their cult names of Baphomet and Selene. Rumour had it that they were brother and sister.

The last word should go to Shelley’s

Prometheus Unbound

which was, in a way, what had turned my vague suspicion of Soames into a conviction, so to speak:

For know that there are two worlds of life and death:

One which thou beholdest; but the other

Is underneath the grave, where do inhabit

The shadows of all forms that think and live

Till death unite them and they part no more . . .

THE TIME OF BLOOD

The dream came again last night with greater intensity.

It was a warm night and so in my dream I got out of bed to open the window, but the view that met me was not the familiar one of the town square and the

mairie

. Instead, under the moonlight, a great sea stretched from a distant horizon right up my hotel’s façade against which it slapped and lapped. It was not a rough sea, but something stirred beneath its surface like a restless sleeper under a blanket. Then from the far distance a speck of white began to move towards me. The speck resolved itself into a young woman in a white shift streaked and splashed with blood and she was running over the sea towards me. I could see now that, as her bare feet struck the surface of the sea, it sent up little splashes onto the bottom of her shift, and the splashes were not of water but red blood. So, as she ran towards me over the sea of blood, she became bloodier and bloodier from the splashes. I could see that her eyes were bright and fixed on me with a dreadful purpose. By this time I had become aware that I was dreaming, and I knew that it was absolutely necessary that I should wake before she reached me. I began to struggle in the straitjacket of sleep which held me sluggish and half paralysed. At last I snapped the bonds and broke the surface into wakefulness, sweating and struggling for breath. The room was stifling, so I walked to the window, opened it and looked out. The

mairie

and the town square stood still under the moonlight. Far away on a road below the town, a solitary motorbike roared its way to an unknown destination, an oddly reassuring sound.

**

Montjouarre in Burgundy is one of those French provincial towns you pass through on the way to somewhere else. You might even have broken your journey there for a coffee or a beer, because it is a pleasant looking if unspectacular place. It is situated on the Petit Morin, a tributary of the Marne, in fertile arable land. It has a fine Romanesque church on its highest point and near to the war memorial in the municipal gardens can be seen the ruins of an Ursuline convent built in the sixteenth century, but they are neither extensive, nor particularly interesting. The former convent had been the headquarters of the local Gestapo and was razed to the ground when the Germans withdrew in 1944.

Two days ago I arrived there on a soft grey September afternoon when the whole town seemed to be so fast asleep that I wondered if it would ever wake up. I booked into the Hotel du Commerce in the main square, then walked across it to the

mairie

which stood opposite. There I managed to rouse a somnolent concièrge to make an appointment to see M. Le Maire the following morning.

It was three o’clock in the afternoon, and there was nothing else to do. I looked at the church and then walked into the municipal gardens. In a dusty open space flanked by two rows of heavily pollarded plane trees stood the war memorial. It was carved from a mottled grey stone and showed a stolid, bucolic looking

poilu

, in an aggressive pose, rifle clutched in his big, clumsy stone hands

.

Underneath the words MORT POUR LA PATRIE was a long list of those from Montjouarre who had been killed in the First World War. A shorter list of names from the 1939-1945 conflict were carved on the reverse of the monument. The stone

poilu,

turning his head, stared fixedly, and, as I thought, rather fearfully at the ruins of the convent which were situated in the shade of a grove of plane trees to his left. I walked in the direction of the

poilu’s

gaze towards the ruins, because, after all, it was they which had brought me to the little town of Montjouarre.

For the most part I could barely see the outline of the foundations. Here or there a wall was standing which showed an architectural feature of some sort, an arched entrance, or a traceried window. Where there had once been flagstones there was grass, criss-crossed by yellow trackways where countless feet and bicycle wheels had worn through the sward to the sandy clay beneath. I sat down on a stone bench, and stared at a bare archway at the base of which had been put a small notice.

ABBAYE DU SAINT ESPRIT, XVIième SIÈCLE

A sudden little wind whipped up a few newly fallen leaves and sent them eddying across the grass before they flattened themselves against one of the convent walls. I felt cold and damp. I would rather spend my time reading in my dreary hotel room than sitting here where the air seemed loaded with unspecified threat.

**

For some years I had been researching a book about Fénelon, Bossuet and the controversy over that extraordinary mystic Madame Guyon in late seventeenth century France. Researches led me first to the Bibliothèque Nationale, then to the cathedral archives at Meaux where Bossuet had been bishop for the last twenty-three years of his life. Much of his correspondence is easily accessible. The French revere this great preacher, theologian and controversialist so that almost everything he wrote has been published. But, like most scholars, I dream of finding that little cache of enormously significant documents which have somehow escaped the defiling hands of time and scholarship.

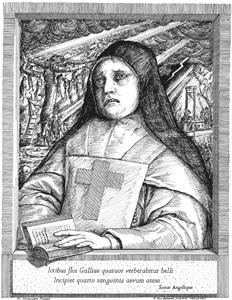

In the cathedral archives at Meaux are a number of documents relating to Bossuet’s time as bishop there. They are mostly routine stuff: charter renewals, ecclesiastical licenses, reports of legal disputes over church lands. Perhaps the most interesting papers—and even they are not that interesting—are those relating to the annual visitations which Bossuet made to the convents, abbeys and monasteries in his diocese. Being a strict and upright churchman he was capable of making very trenchant remarks wherever he found that discipline was lax, or the finances disordered. I was skimming through these, looking for any letters, indeed anything in Bossuet’s own hand when, among the papers relating to a foundation of Ursuline nuns at the Abbey of Montjouarre, some twelve miles southwest of Meaux, I discovered a note—not, however, in Bossuet’s own hand—which intrigued me. It was written in sepia ink, possibly by Bossuet’s secretary, Ledieu, on a single sheet of paper, and was dated May 5th 1704, a little under a month after the Bishop’s death. It read: ‘All papers relating to Madeleine Lapige, née Chanal (Sister Angélique) returned to Montjouarre at the request of the Lady Abbess, Mme de Lonchat.’

Though I looked everywhere I could find only the most cursory reference to the Abbey of Montjouarre and none whatsoever to Sister Angélique. I might have stopped there except that on my return to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris I decided to look up Montjouarre in the indexes and see what books they had on the subject. A rather dull-looking local history written in the 1950s yielded the information that the Abbey of Montjouarre had been almost completely destroyed in the Second World War. It had however not been an abbey for some time, the nuns having been expelled and the building turned into a military academy by Napoleon. A footnote informed me that at the time of the Abbey’s conversion from a spiritual to a warlike function all the papers relating to the Abbey on the command of the Emperor had been moved to the

mairie

. It was somehow a typically Napoleonic act: the attention to detail, the respect for the past combined with ruthless secularism. Now that I knew there was a possibility of these papers still existing I felt obliged to pursue my researches into them, even though they probably had only a marginal connection with my chosen subject. As it happened, I felt the need for a break, so the following day I left Paris for Montjouarre.

**

The next morning I was at the

mairie

sitting opposite a neat, bright-eyed, plump little man in a large, sombre office. My experience of French mayors is slight but on the whole very favourable. Their attitude is serious but relaxed and affable and they are often men of culture with a high regard for the arts. M. Georges Hubertin, Mayor of Montjouarre, was no exception. After a brief interview he told me that there was indeed a box of papers relating to the Abbey and invited me to dinner at his home that night to discuss the matter further.

The dinner was excellent: Cepes à la Bordelaise, followed by Chateaubriand; the wine was a superb Chambertin; Madame Hubertin and their two teenage daughters were charming. The French have a natural reverence for scholarship and intellect and I was an object of particular interest in being an English intellectual with an interest in French culture. After dinner Hubertin and I were left to discuss matters over coffee and cognac.

‘I have only heard of the Abbey papers mentioned once before,’ said M. Hubertin. ‘In about 1890, the local priest, a man with some intellectual pretensions, asked to see the papers, and, having done so, requested that he might take them away and destroy them, claiming the right as a priest of the Church to have jurisdiction over ecclesiastical documents. The then mayor, who happened to be my great-grandfather, also a proud bearer of the name of Hubertin, was most indignant that such ancient documents should be consigned to the flames. Besides, he was a good freethinker and had no great love for M. Le Curé. However, he was a politician and therefore always ready to compromise for the sake of peace, so he promised that these papers should be placed in a box and locked up. He assured M. Le Curé that the box would not be opened for a hundred years and that the key to the box should be passed from Mayor to Mayor with this explicit instruction. M. Le Curé was not happy with the arrangement, but he had to content himself in the face of my great-grandfather’s inflexible will. He was heard to mutter that he wished he had destroyed them while he had the chance. Not long after he died in what I believe were bizarre circumstances. I cannot remember what they were: I will try to find out for you. And now the one hundred years is up, Monsieur. More cognac?’

It was that night—the night before last—that I had the dream for the first time. The first time it merely puzzled me.

**

The following morning M. Hubertin and I met at the

mairie

and went down into the cellars where the papers were kept. He told me with great pride how for nearly six months towards the end of the war two Jewish families had been hidden by his father and uncle in these cellars, ‘right under the very noses of the Gestapo!’

After some rummaging around we discovered a very large japanned tin box with a label on it announcing that it contained papers relating to the Abbaye du Saint Esprit. As he did not want them to be moved from the

mairie

, Hubertin arranged that a small room in the building be allocated to me for their inspection. I could have access to it in normal office hours, and it would be locked at night. If, at the end of my examination, I required any copying to be done, this could be negotiated. It seems a very fair arrangement, though the prospect of spending a week or so in Montjouarre at the Hotel du Commerce is not altogether agreeable to me.

The papers relate to every part of the Abbey’s history from the foundation in 1583 until its dissolution. I soon discovered that the papers concerning Sister Angélique mentioned in the archives at Meaux consist mainly of a correspondence between Jacques-Benigne Bossuet, Bishop of Meaux, and Madame de Lonchat, Abbess of Montjouarre.

At this point let me insert a brief note about Madame de Lonchat. She had been the wife of the Viscomte de Lonchat and, like most of the aristocracy, had spent much of her life in the suffocating splendour of Versailles at the Court of the Sun King, Louis XIV. There she had enjoyed an unusual reputation for virtue and piety. On the death of her husband in 1692 she determined to leave the court immediately in order to lead a life of contemplative prayer. Within a very few years, thanks to the influence of her friend Madame de Maintenon (by then Louis’ morganatic wife), she had became Abbess of the Ursuline Convent of Montjouarre. Aristocratic Abbesses were a feature of seventeenth century France, and, while some were lax and dissolute, many, like Madame de Lonchat, were conscientious, even if they had obtained their positions through birth and influence.

The letters begin in February 1702 when Bossuet was seventy-five, two years away from his death. At that time he was a revered figure, but no longer the power in the land that he had once been. Only three years before the famous controversy with Fénelon had ended with an apparent victory for Bossuet, but many believed that his reputation had been tarnished by the scandal it had caused.

**

From Mme de Lonchat, Abbess of Montjouarre to M. de Meaux 16th February 1702.

Your grace’s last visitation was a precious encouragement to us all. My Sisters have well heeded your counsel regarding over-scrupulousness and excessive mortification. But I write to you because I have a concern regarding one of my charges, Sister Angélique, not long consecrated in our Sisterhood. You may remember this girl. The daughter of a prosperous grain merchant, M. Chanal, she came to our Abbey to be educated with her sisters at the age of nine. She proved herself most apt and obedient, not only in her schooling but in her devotions, and she endeared herself to all here by her sweetness and natural piety. When the time came for her to be removed from our care at the age of sixteen, she begged to be allowed to stay and become a postulant of our order. M. Chanal objected strongly for he had plans to marry her off advantageously as she was a girl of great beauty. Madeleine, as she was then called before she took the name of Sister Angélique at her clothing, resisted his wishes most vehemently and ran away from home several times to find refuge with us. At last we appealed to you on her behalf to arbitrate in this matter and you yourself were gracious enough to speak to the father and persuade him that God had indeed called his daughter to a life of prayer and renunciation.