The Complete Yes Minister (45 page)

Desmond was puzzled. He thought a decision was a decision. I explained that a decision is a decision

only

if it is the decision you wanted. Otherwise, of course, it is merely a temporary setback.

only

if it is the decision you wanted. Otherwise, of course, it is merely a temporary setback.

Ministers are like small children. They act on impulse. One day they want something desperately, the next day they’ve forgotten they ever asked for it. Like a tantrum over a rice pudding – won’t touch it today and asks for two helpings tomorrow. He understood this.

Desmond asked me if I intended to tell him that I refused to accept his decision. The man really is dense! I explained that, on the contrary, I shall start off by accepting Hacker’s decision enthusiastically. Then I shall tell him to leave the details to me. [

Appleby Papers 97

/

JZD

/

31f

]

Appleby Papers 97

/

JZD

/

31f

]

[

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

September 15th

We had the urgent meeting with Sir Desmond Glazebrook today. It went off most satisfactorily and presented no problems, largely because it was preceded by a meeting between me and Sir Humphrey in which I ensured his full co-operation and support.

When Humphrey popped in for a quick word before the meeting he outlined Glazebrook’s case for a tower block:

1) There are already several tower blocks in the area

2) Their International Division is expanding rapidly and needs space. And international work brings in valuable invisible exports

3) Banks need central locations. They can’t move some of it elsewhere

4) It will bring in extra rate revenue for the city

This is a not unreasonable case. But, as I pointed out to Humphrey, it’s a typical bank argument, money, money, money! What about the environment? What about the beauty?

Humphrey was impressed. ‘Indeed Minister,’ he agreed. ‘Beauty. Quite.’ He told Bernard to make a note of it.

I could see I was winning. ‘And what about our children? And our children’s children?’

Again he agreed, and told Bernard to be sure he make a note of ‘children’s children’.

‘Who are you serving, Humphrey?’ I asked. ‘God or Mammon?’

‘I’m serving you, Minister,’ he replied.

Quite right. I told Bernard to show Glazebrook in, and Sir Humphrey said to me: ‘Minister, it’s entirely your decision. Entirely your decision.’ I think he’s getting the idea at last! That I’m the boss!

Desmond Glazebrook arrived with an architect named Crawford, complete with plans. They began by explaining that they would be making a formal application later, but they’d be grateful for any guidance that I could give them at this stage.

That was easy. I told them that I had grave misgivings about these tower blocks.

‘Dash it, this is where we make our profits,’ said Sir Desmond. ‘Six extra storeys and we’ll really clean up. Without them we’ll only make a measly twenty-eight per cent on the whole project.’

I stared at him coldly. ‘It’s just profits, is it, Sir Desmond?’

He looked confused. ‘Not

just

profits,’ he said, ‘it’s profits!’

just

profits,’ he said, ‘it’s profits!’

‘Do you ever think of anything except money?’ I asked him.

Again he looked completely blank. ‘No. Why?’

‘You don’t think about beauty?’

‘Beauty?’ He had no idea what I was driving at. ‘This is an office block, not an oil-painting.’

I persevered. ‘What about the environment?’ I enquired.

‘Well . . .’ he said, looking at Humphrey for help. Sir Humphrey, to his credit, gave him none. ‘Well, I promise you we’ll make sure it’s part of the environment. I mean, it’s bound to be, once it’s there, isn’t it?’

I had reached my decision. ‘The answer’s no,’ I said firmly.

Crawford the architect intervened. ‘There is just one thing, Minister,’ he said timidly. ‘As you will remember from the papers, similar permission has already been given for the Chartered Bank of New York, so to refuse it to a British bank. . . .’

I hadn’t realised. Bernard or Humphrey should have briefed me more thoroughly.

I didn’t answer for a moment, and Sir Desmond chipped in:

‘So it’s all right after all, is it?’

‘No it’s not,’ I snapped.

‘Why not, dammit?’ he demanded.

I was stuck. I had to honour our manifesto commitment, and I couldn’t go back on my widely-reported speech yesterday. But if we’d given permission to an American bank . . .

Thank God, Humphrey came to the rescue!

‘The Minister,’ he said smoothly, ‘has expressed concern that a further tall building would clutter the Skyline.’

I seized on this point gratefully. ‘Clutter the skyline,’ I repeated, with considerable emphasis.

‘He is also worried,’ continued Sir Humphrey, ‘that more office workers in that area would mean excessive strain on the public transport system.’

He looked at me for support, and I indicated that I was indeed worried about public transport. Humphrey was really being most creative. Very impressive.

‘Furthermore,’ said Humphrey, by now unstoppable, ‘the Minister pointed out that it would overshadow the playground of St James’s Primary School here . . .’ (he pointed to the map) ‘and that it would overlook a number of private gardens, which would be an intrusion of privacy.’

‘Privacy,’ I agreed enthusiastically.

‘Finally,’ said Humphrey, lying through his teeth, ‘the Minister also pointed out, most astutely if I may say so, that your bank owns a vacant site a short way away, which would accommodate your expansion needs.’

Sir Desmond looked at me. ‘Where?’ he asked.

I stabbed wildly at the map with my finger. ‘Here,’ I said.

Desmond looked closely. ‘That’s the river, isn’t it?’

I shook my head with pretended impatience at his stupidity, and again Humphrey saved the day. ‘I think the Minister was referring to

this

site,’ he said, and pointed with precision.

this

site,’ he said, and pointed with precision.

Sir Desmond looked again.

‘Is that ours?’ he asked.

‘It is, actually, Sir Desmond,’ whispered Crawford.

‘What are we doing with it?’

‘It’s scheduled for Phase III.’

Sir Desmond turned to me and said, as if I hadn’t heard, ‘That’s scheduled for Phase III. Anyway,’ he went on, ‘that’s at least four hundred yards away. Difficult for the Board to walk four hundred yards for lunch. And impossible to walk four hundred yards back afterwards.’

I felt that I’d spent enough time on this pointless meeting. I brought it to a close.

‘Well, there it is,’ I said. ‘You can still put in your formal application, but that will be my decision, I’m sure.’

Bernard opened the door for Sir Desmond, who stood up very reluctantly.

‘Suppose we design a different rice pudding?’ he said.

I think he must be suffering from premature senility.

‘Rice pudding?’ I asked.

Humphrey stepped in, tactful as ever. ‘It’s er . . . it’s bankers’ jargon for high-rise buildings, Minister.’

‘Is it?’ asked Sir Desmond.

Poor old fellow.

After he’d gone I thanked Humphrey for all his help. He seemed genuinely pleased.

I made a point of thanking him

especially

because I know that he and Desmond Glazebrook were old chums.

especially

because I know that he and Desmond Glazebrook were old chums.

‘We’ve known each other a long time, Minister,’ he replied. ‘But even a lifelong friendship is as naught compared with a civil servant’s duty to support his Minister.’

Quite right too.

Then I had to rush off to my public appearance at the City Farm.

Before I left, Humphrey insisted that I sign some document. He said it was urgent. An administrative order formalising government powers for temporary utilisation of something-or-other. He gave me some gobbledegook explanation of why I had to sign it rather than its being put before the House. Just some piece of red tape.

But I wish he wouldn’t always try to explain these things to me when he can see I’m late for some other appointment.

Not that it matters much.

SIR BERNARD WOOLLEY RECALLS:

1

1

Hacker was being thoroughly bamboozled by Sir Humphrey and was completely unaware of it.

The Administrative Order in question was to formalise government powers for the temporary utilisation of unused local authority land until development commences, when of course it reverts to the authority.

In answer to Hacker’s question as to why it was not being laid before the House, Sir Humphrey gave the correct answer. He explained that if it were a statutory instrument it would indeed have to be laid on the table of the House, for forty days, assuming it were a negative order, since an affirmative order would, of course, necessitate a vote, but in fact it was not a statutory instrument nor indeed an Order in Council but simply an Administrative order made under Section 7, subsection 3 of the Environmental Administration Act, which was of course an enabling section empowering the Minister to make such regulations affecting small-scale land usage as might from time to time appear desirable within the general framework of the Act.

After he had explained all this, to Hacker’s evident incomprehension, he added humorously, ‘as I’m sure you recollect only too clearly, Minister.’ Appleby really was rather a cad!

I must say, though, that even I didn’t grasp the full significance of this move that afternoon. I didn’t even fully comprehend, in those days, why Humphrey had persuaded Hacker to sign the document on the pretext that it was urgent.

‘It was not urgent,’ he explained to me later, ‘but it was important. Any document that removes the power of decision from Ministers and gives it to us is important.’

I asked why. He rightly ticked me off for obtuseness. Giving powers of decision to the Service helps to take government out of politics. That was, in his view, Britain’s only hope of survival.

The urgency was true in one sense, of course, in that whenever you want a Minister to sign something without too many questions it is always better to wait until he is in a hurry. That is when their concentration is weakest. Ministers are always vulnerable when they are in a hurry.

That is why we always kept them on the go, of course.

[

Hacker’s diary for that day continues – Ed

.]

Hacker’s diary for that day continues – Ed

.]

It’s always hard to find something to make a speech about. We have to make a great many speeches, of course – local authority elections, by-elections, GLC elections, opening village fetes or the new old people’s home, every weekend in my constituency there’s something.

We must try to have

something

to say. Yet it can’t be particularly new or else we’d have to say it in the House first, and it can’t be particularly interesting or we’d already have said it on TV or radio. I’m always hoping that the Department will cook up something for me to talk about, something that we in the government would have to be talking about anyway.

something

to say. Yet it can’t be particularly new or else we’d have to say it in the House first, and it can’t be particularly interesting or we’d already have said it on TV or radio. I’m always hoping that the Department will cook up something for me to talk about, something that we in the government would have to be talking about anyway.

Equally, you have to be careful that, in their eagerness to find something, they don’t cook up anything too damn silly. After all, I’ve got to actually get up and say it.

Most civil servants can’t write speeches. But they can dig up a plum for me (occasionally) and, without fail, they should warn me of any possible banana skins.

Today I planned to make a sort of generalised speech on the environment, which I’m doing a lot of recently and which seems to go down well with everyone.

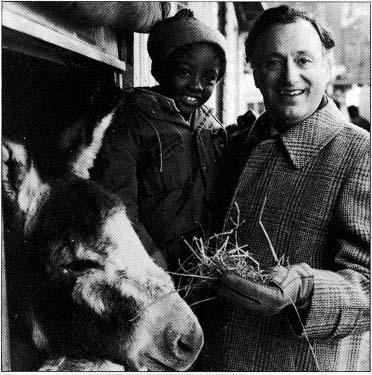

Hacker was persuaded to pose for the above photograph against his better jugement, because he was unwilling to appear ‘a bad sport’ in public. He subsequently had the photograph suppressed but it was released under the Thirty-year Rule (DAA Archives)

At the City Farm we were met by a brisk middle-class lady called Mrs Phillips. She was the Warden of the City Farm. My party simply consisted of me, Bill Pritchard of the press office, and Bernard.

We were asked to drive up to the place two or three times in succession, so that the television crew could film us arriving.

The third time seemed to satisfy them. Mrs Phillips welcomed me with a singularly tactless little speech: words to the effect of ‘I’m so grateful that you could come, we tried all sorts of other celebrities but nobody else could make it.’

I turned to the cameraman from the BBC and told him to cut. He kept filming, impertinent little man. I told him again, and then the director said cut so he finally did cut. I instructed the director to cut Mrs Phillips’ tactless little speech right out.

‘But . . .’ he began.

‘No buts,’ I told him. ‘Licence fee, remember.’ Of course I said it jokingly, but we both knew I wasn’t joking. The BBC is always much easier to handle when the licence fee is coming up for renewal.

I think he was rather impressed with my professionalism and my no-nonsense attitude.

We went in.

I realised that I didn’t know too much about City Farms. Furthermore, people always like to talk about themselves and their work, so I said to Mrs Phillips – who had a piglet in her arms by this time – ‘Tell me all about this.’

Other books

Carolyn Davidson by Runaway

Arkadian Skies: Fallen Empire, Book 6 by Lindsay Buroker

The Demon-Eater: Hunting Shadows (Book One, Part One by Devin Graham

Spy Games by Adam Brookes

Pamela Dean by Tam Lin (pdf)

Happy People Read and Drink Coffee by Agnes Martin-Lugand

Jules (Golden Streak Series Book 5) by Kathi S. Barton

The Means of Escape by Penelope Fitzgerald

Castles by Julie Garwood

His Canvas by Ava Lore