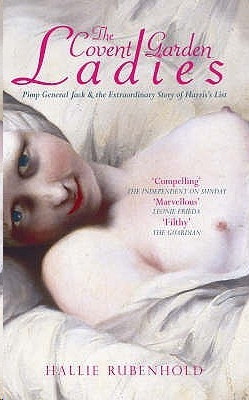

The Covent Garden Ladies

Read The Covent Garden Ladies Online

Authors: Hallie Rubenhold

Tags: #History, #Social History, #Social Science, #Pornography

ABOUT THE BOOK

In 1757, a down-and-out Irish poet, the head-waiter at Shakespear’s Head Tavern in Covent Garden, and a celebrated London courtesan became bound together by the publication of a little book:

Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies

. This salacious publication detaling the names and ‘specialities’ of the capital’s prostitutes eventually became one of the eighteenth century’s most successful and scandalous literary works, selling 250,000 copies. During its heyday (1757-95)

Harris’s List

was the essential accessory for any serious gentleman of pleasure. Yet beyond its titillating passages lay a glimpse into the sex lives of those who lived and died by the

List

’s profits during the Georgian era.

The Covent Garden Ladies

tells the story of three unusual characters: Samuel Derrick, John Harrison (aka Jack Harris) and Charlotte Hayes, whose complicated and colourful lives were brought together by this publication. The true history of the book is a tragicomic opera motivated by poverty, passionate love, aspiration and shame. Its story plunges the reader down the dark alleys of eighteenth-century London’s underworld, a realm populated by tavern owners, pimps, punters, card sharks and of course, a colourful range of prostitutes and brothel-keepers.

CONTENTS

Glossary of Eighteenth-Century Terms

5. The Rise of Pimp General Jack

9. An Introduction to Harris’s Ladies

14. Santa Charlotta of King’s Place

16. ‘Whore Raising, or Horse Racing; How to Brood a Mare or Make Sense of a Foal-ly’

Appendix: A List of Covent Garden Lovers

Extract from

Mistress of My Fate

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The researching and writing of this work has been a fascinating voyage of discovery, not only for me but for a number of others involved. First and foremost I would like to express my gratitude to Jonathan Reeve at Tempus for his insight, his assistance and for his unwavering faith in this book. An expression of thanks is also due to Frances Wilson for taking the time to read the manuscript in its early incarnation.

Similarly, the completion of my research would not have been possible without the contributions of several individuals. Elizabeth Denlinger’s generosity in sharing her unpublished research and engaging with me in lengthy ‘e-conversations’ about the

Harris’s List

has not gone unappreciated. Neither has the interest and assistance demonstrated by Susan Walker at the Lewis Walpole Library. Kieran Burns, Helen Roberts, Sarah Peacock, Paul Tankard, Robin Eagles, Matthew Symonds, James Mitchell, Declan Barriskill and Elen Curran have all been instrumental in helping to pull together the various strands of this history. I would also like to extend my gratitude to the staff at the British Library, the National Art Library, the London Metropolitan Archives and the Westminster City Archives, where the majority of my research was conducted.

Finally, but certainly not least on my roll of honours, my husband, Frank deserves a special commendation for agreeing to share his home and his life with Jack Harris, Samuel Derrick and the O’Kelly family for two long years. Without his support and that of my parents it is unlikely that their stories would have been given the airing they deserve.

GLOSSARY

Abbess: the female keeper of a high-class brothel.

Adventurer: a con man, usually well dressed and seemingly genteel.

Aretino’s

Postures:

a popular series of engravings illustrating the sexual positions featured in Pietro Aretino’s 1534 work,

Sonetti Lussuriosi

.

Bawd: a woman who procures prostitutes.

Bawdy House: a brothel.

Bagnio: a bath house, usually a location where sexual favours could be received.

Bilk: to cheat one out of their pay.

Black Legs: a gambler who bets on horse races and other outdoor sports. ‘Black legs’ refer to the tall black boots generally worn by such men.

Blood: ‘a riotous and disorderly fellow’.

Bow Street: the headquarters of the magistrate, John Fielding, and his flying squad, the ‘Bow Street runners’.

Bridewell: the Clerkenwell-based prison for prostitutes.

Buck: ‘a man of spirit’ or a debauchee.

Bulk Monger: a homeless prostitute who lives and plies her trade from the benches below shop fronts.

Bully: a man who acts as a protector to a prostitute, also the eighteenth-century equivalent of a bouncer.

Bunter: a destitute prostitute.

Cantharides: aphrodisiacs.

Chariot: a phaeton or two-wheeled carriage (could also be a reference to a coach).

Chair/Sedan Chair: a chair enclosed within a small cabin and carried on two poles by two bearers. Usually used for covering short distances.

Clap: ‘a venereal taint’, usually gonorrhoea.

Compter/Round House: a local lock-up or gaol.

Cull/Cully: a prostitute’s customer.

Cundum: a condom. In the eighteenth century these were generally made of animal intestine and fixed in place with a ribbon. Used as a prophylactic rather than a contraceptive device.

Disorderly House: the legal term used to describe a brothel.

The Fleet: London’s main debtor’s prison.

Gin: a cheap, frequently adulterated alcoholic drink favoured by the London poor.

High-keeping: the extravagant maintenance of a prostitute in expensive lodgings.

‘In keeping’: the state of being financially supported by one man as his mistress.

Jellies/Jelly Houses: a gelatine dessert favoured by both high and low society. Jelly houses, which were a mid-eighteenth-century fad, were outlets that specifically sold moulded jellies. They tended to be patronised by prostitutes.

The King’s Bench Prison: the Southwark-based prison generally used for holding debtors and those guilty of libel.

The Lock Hospital: a hospital for the cure of venereal disorders. Founded in 1746.

The Magdalen Hospital: a reformatory for repentant prostitutes.

The Marshalsea: a Southwark-based prison mainly used to house debtors in the eighteenth century.

Mercury: the primary ingredient in treatments for venereal disorders.

Newgate: London’s chief prison, where its most dangerous felons were held.

Night Constable: a parish constable on duty in the evenings.

Night Watch: the lowest ranking law-enforcers. Notorious for their dishonesty and their susceptibility to bribes.

Nunnery: a high-class brothel, usually based on or around King’s Place.

Panderer: a slightly higher-ranking pimp who worked within doors.

Pimp: a man who seeks ‘to bring in customers and to procure … wenches’.

‘Plead her belly’: when a woman claims she is pregnant in order to save herself from execution.

Pox: syphilis

Rake: ‘a lewd debauched man’. Other terms include ranger or roué.

Register office: an employment office where jobs were advertised.

Sal/Salivation/‘down in a sal’: someone in the midst of a mercury treatment for venereal disease. Among other symptoms, the ingestion of mercury brought on profuse salivation.

Serail: a high class, French-style brothel.

Sharper: a cheat, ‘one who lives by his wits’.

Spunging House: a bailiff’s lock-up ‘to which persons arrested are taken till they find bail, or have spent all of their money’.

Tyburn: the location where public hangings were conducted during the eighteenth century.

1

THE

CURTAIN Rises

ALTHOUGH YOU MAY

not recognise it, you are standing in Covent Garden. It may look strange to you without its glass and steel market arches and its swirl of tourists. The buskers are gone, as are the rickshaw bicycles and shops peddling plastic gadgetry. What is left behind is the Piazza in

puris naturalibus

, in its mid-eighteenth-century state, complete with cobblestones, dust and open drains.

It’s a colourful place, even by the first thrust of morning light. At this early hour, the market square is alive with London life. Fruit and vegetable sellers, carters, ballad singers, knife grinders and milkmaids circle one another in their daily dance of work. Under wide-brimmed straw bonnets, women with red elbows balance baskets of produce on their hips. Men in wool frock coats or leather aprons toil, with their tri-cornered hats pulled over their sleepy eyes. There are children running barefoot chasing dogs. There are old men hobbling on makeshift walking sticks as crooked as their backs. There are toothless, wrinkled women, who are much younger than they look. Many of those who have come to haggle, wrapped up against the dawn’s chill, belong to the metropolis’s army of domestic servants. They will scurry back to their employers’ homes with heavy baskets before their masters and mistresses have stirred from their beds.

Of course, this visual carnival is not without its scents and sounds. The market, stacked high with fresh and rotting produce, emits a sweet stench of cabbage and apple. The wet pungency of horse droppings is equally unavoidable, as is the constant presence of yellowy coal smoke and the incense of burning wood. It is, however, the murky puddles that give off some of the more unexpected odours. In the absence of an operational sewage system, London droops under its own stink. The wealthy have become quite adept at fending off the sudden olfactory assaults of decomposition and human waste, hiding their noses against perfumed handkerchiefs and nosegays. The poor, on the other hand, have just learned to live with the unpleasantness. Those of the labouring classes discovered long ago that many of their hardships could be smothered through song, and it is their melodies that take to the Piazza’s air. Many of the tunes whistled or hummed come from those heard at the two local theatres. Music is one of the mainstays of an evening’s entertainment at the Covent Garden theatre, sitting at the eastern edge of the Piazza, and its rival, the Theatre Royal on Drury Lane. This part of town has always been a spot for instruments and voices, day or night. When the stage lights are extinguished, the market provides a chorus of sound instead. Higglers cry their wares, their tones floating together discordantly. Between melodic solicitations to buy quinces and oranges, they flirt and banter, challenging one another boisterously. Above their declarations can be heard yet another type of music, the urban clatter of horses’ hooves, the squeak and bounce of wooden wheels, doors slamming, the roll of barrels, the cries of babies, the squeals and brays of animals. There are no silently ticking engines, no electricity or automation to do their work for them, only the grunts and sweat of men and beasts.

Despite the pulsing activity of the market place, there is much more to Covent Garden than this hustle of morning commerce. Not everyone comes here to purchase fruit for their pies and puddings. As morning matures into afternoon and the vendors have sold the last of their wares, the Piazza’s more lucrative trade begins to stir from its slumber. The centre of the action shifts from the ring-fenced vegetable exchange at the square’s heart to the stone-faced buildings at its periphery.

From our vantage point looking northwards, a number of the more infamous haunts are visible. In the most north-easterly corner, slightly

obscured behind the arcaded walk, lies one of the set pieces of our story. Beneath a magnificent swinging signboard, featuring the face of England’s best-loved bard, is the entrance to a tavern known as the Shakespear’s Head. The sordid details of what transpired in its dim rooms I will leave for later. Next door, to the south of the Shakespear’s Head, is the Bedford Coffee House, a slightly more respectable establishment, although only just. Its distinguished dramatic and literary clientele bestow on it a certain fashionable cachet, which barely saves it from sharing its neighbour’s dubious stigma. On the opposite side of the Shakespear, to the north, are the elegant premises of the bawd, Mrs Jane Douglas. As the tavern drunks ensure that Mother Douglas’s girls never go patron-less, business thrives well into the early 1760s. After that time, any woman of Jane Douglas’s profession will be turning her sights towards the more fashionable parts of town, first Soho and then St James’s, Mayfair and Piccadilly. For the moment, however, Jane Douglas and her sister Covent Garden procuresses are doing quite well, nestled in this nook of sin. The keepers of Haddock’s Bagnio, on the Piazza, just south of the corner of Russell Street, are also doing a booming trade. The aristocratic set finds the novelty of indulging in a Turkish bath, a meal and the company of a prostitute all under one roof quite pleasing. On any given night they can be seen bumbling between Haddock’s and the adjoining Bedford Arms Tavern (not to be confused with the Bedford Coffee House, or the Bedford Head Tavern on Maiden Lane). In fact, there is so much here in the way of carnal diversion that you might be forgiven for omitting to notice the parish church, St Paul’s Covent Garden, in all of its austere beauty, occupying the west side of the square. It has sat there, silently observing, for over a hundred years.