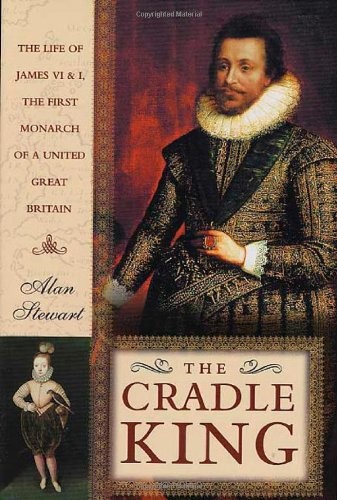

The Cradle King

Authors: Alan Stewart

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History, #Biography, #Christian

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Contents

12. Reformation and Combustion

13. Two Twins Bred in One Belly

Acknowledgements

Work on this book started at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC and finished at the British Library in London, and I am indebted to the librarians and staff of both these great institutions. I am immensely grateful to the Folger for giving me a Short-Term Fellowship in 2000, and to Tom Healy and my colleagues at Birkbeck for allowing me generous research leave. Maggie Pearlstine and John Oates at Maggie Pearlstine Associates encouraged me throughout. At Chatto & Windus, Rebecca Carter was a supportive and challenging editor.

I could not have written

The Cradle King

without the insights of those scholars who have broadened and deepened our knowledge of all things Jacobean since D.H. Willson’s 1956 biography of James. I learned particularly from the work of (in alphabetical order) G.P.V. Akrigg, Leeds Barroll, David Bergeron, Caroline Bingham, Antonia Fraser, Jonathan Goldberg, Maurice Lee Jr., Roger Lockyer, Maureen Meikle, Stephen Orgel, Curtis Perry, David Stevenson, Roy Strong and Jenny Wormald. For ideas, suggestions, comments and help of many kinds, I am grateful to Tom Betteridge, Warren Boutcher, Tricia Bracher, Jerry Brotton, Stephen Clucas, Erica Fudge, Donna Hamilton, James Knowles, Gordon McMullan, Steven May, David Norbrook, Alex Samson, James Shapiro, Bruce Smith, Sue Wiseman, Heather Wolfe and Elizabeth Wood.

Finally, my sincere thanks go to the friends who saw me through: Patricia Brewerton, James Daybell, Will Fisher, Eliane Glaser, Andrew Gordon, Lisa Jardine, Simon Lloyd-Owen, Lloyd Meiklejohn, Kirk Melnikoff, Chris Ross, Richard Schoch, Goran Stanivukovic, Garrett Sullivan and especially Tyler Smith.

Prologue

I

N

1603, J

AMES

I, King of England, made a visit to one of the most southerly of his new possessions, Beaulieu, in the New Forest. All the local nobility and gentry turned out to get their first glimpse of the King of Scots who had just become their own sovereign. Among them was the eighteen-year-old John Oglander, a son of the local landed gentry. Over fifty years later, Oglander jotted down his memories of that royal visit.

1

By then, his life was consumed by the fight to save James’s son, the embattled King Charles. But his image of James was far from complimentary. ‘King James I of England was the most cowardly man that ever I knew,’ he started. When James came to Beaulieu, he recalled, ‘he was much taken with seeing the little boys skirmish, whom he loved to see better and more willingly than men.’ The pantomime of juvenile combat suited the King far better than the real, very bloody thing. ‘He could not endure a soldier or to see men drilled, to hear of war was death to him, and how he tormented himself with fear of some sudden mischief may be proved by his great quilted doublets, pistol-proof, was also his strange eyeing of strangers with a continual fearful observation.’

Why would Oglander, a staunch royalist, write such a thing? His other notes on the King were positive enough. ‘Otherwise’, he wrote, James was ‘the best scholar and wisest prince for general knowledge that ever England had, very merciful and passionate, liberal and honest.’ He was ‘a great politician and very sound in the reformed religion’. He ‘spoke much and as well as any man, or rather better.’ And he was ‘the chastest prince for women that ever was, for he would often swear that he had never known any other woman than his wife.’ Although he was known to be ‘excessively taken with hunting’ – indeed, he was notorious for it – ‘he did not, or could not’, according to Oglander, use much ‘bodily action’, so that ‘his body for want of use’ grew ‘defective’. In Oglander’s eyes, this was a King for whom theory and rhetoric were never matched by practice. ‘If he had but the power, spirit and resolution to have acted that which he spoke, or done as well as he knew how to do, Solomon had been short of him.’

For Oglander, the answer to this paradox lay in the King’s ‘fearful nature’. Throughout his life, James was noted, and lampooned, for his fear of war, weapons, loud noises and unexplained strangers. He referred to them, in his usual grandiose style, as his ‘daily tempests of innumerable dangers’. Speaking to the English Parliament after he survived perhaps the greatest threat of all, the Gunpowder Plot of November 1605, he made his own diagnosis as to the cause of his ‘fearful nature’. They could be traced and dated, he told the Parliament, ‘not only ever since my birth, but even as I may justly say, before my birth: and while I was in my mother’s belly’.

2

CHAPTER ONE

Nourished in Fear

S

COTLAND LOOKED FORWARD

to a great marriage. Mary, although a widow, was still a young, captivating Queen, only twenty-three years old, a tall, auburn-haired woman. She came from ruling the sophisticated French court as the wife of King François II, and preferred to speak, read and write in French. The groom, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, by all accounts was an equally fine-looking man, taller than his bride, blond and elegant, and just nineteen. The French ambassador reported that ‘it is not possible to see a more beautiful Prince, and he is accomplished in all courtly exercises’.

1

On Sunday 29 July 1565, very early in the morning, they were married in the Chapel Royal in the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh.

2

But the ceremony almost didn’t happen. As one observer noted, less than a month before the wedding, Henry did not think himself sufficiently honoured by the prenuptial arrangements Mary proposed. He wanted to reign alongside her as King, to have the ‘Crown Matrimonial’; Mary insisted that he should wait until he came of age and had gained the consent of Parliament. But Henry’s ‘insolent temper’ prevailed,

3

and on the day after the wedding, Henry got his wish. At Edinburgh’s Mercat Cross Henry was formally proclaimed as King of Scots, and the official document dated the event as being ‘of our reigns the first and twenty-third years’, the ordering of the numbers giving Henry’s reign priority over Mary’s. But a proclamation could not change men’s opinions. As ‘King Henry’ was proclaimed, the nobility maintained silence, refusing to cheer their new sovereign. Only his father, the Earl of Lennox, chimed in with the usual ‘God save his Grace!’

4

It’s a mark of how little accepted Henry was as King that to this day historians routinely refer to him as ‘Lord Darnley’.

The new King Henry was competing with a wife who had been Queen of Scots for twenty-three years, since she was a week old. The only legitimate child left by James V at his early death in 1542, Mary had spent only the first six years of her life in Scotland, under a regency government headed by James Hamilton, second Earl of Arran. Through the intervention of her French mother, Marie de Guise, Mary had left for France in 1548 to receive an education: ten years later she married the heir to the French throne. In 1554, Arran stepped aside to allow Marie de Guise to take over as Regent, and Marie did her utmost to strengthen the bond between Scotland and France popularly known as ‘the auld alliance’.

But Marie’s control on the country was never total. Scotland in the 1550s was witnessing the rise of a new religious movement. Protestants, inspired by the ecclesiastical reformations in Germany and England, began to form themselves into a new Church. They were encouraged by the visit of the Calvinist preacher John Knox, who returned to his homeland in 1555 and preached and celebrated communion across the country. When the Scots Parliament met in December 1557 to approve the marriage of their absentee Queen Mary with the French Dauphin François, the Protestant Lords took the opportunity to draw up a formal ‘band’, or alliance, pledging to further the Reformist cause in Scotland against the regime of the Regent Marie. Two years later, the same Protestant Lords, known as the Lords of the Congregation, succeeded in persuading Knox to return to Scotland permanently. By now they were beginning to wage war against the Regent and her French-maintained army. Gradually, the Lords of the Congregation, headed by James V’s illegitimate son Lord James Stewart, pushed the Regent’s forces back to Edinburgh’s port town, Leith, which they fortified in preparation for battle. English forces were sent by Queen Elizabeth to support the Protestant Lords, but the looming war never materialised. In June 1560 Marie de Guise died, and the impetus of her campaign was lost. On 6 July of that year, a peace was declared at Edinburgh, whereby both the French and the English were to leave Scotland; the English used their involvement to broker an agreement that Mary and François would give up their claims to the English throne. Mary’s half-brother Lord James Stewart took control of the country, and imposed a new Reformation on Scotland, adopting a ‘Confession of Faith’ which founded a new Kirk (Church), broadly Calvinist in spirit, outlawing the saying of the Mass and rejecting the authority of the Pope.

5

1560 also saw the death of Mary’s husband King François from an abscess in his ear. As his brother Charles ascended the throne, Mary had no reason to remain in France and was forced back to Scotland. It was not a journey she wished to make. She had been brought up to believe that Scotland was a backward, ignorant, unsophisticated land. At the self-consciously civilised French court, Scotland’s social conventions – fierce loyalties to local magnates, peace kept through strong ‘bonds’ and justice meted out in feuds – were decried as outdatedly feudal at best, barbaric at worst. On reaching Scotland, Mary’s policy of government seems to have been to close her eyes and hope her troubles would melt away. Radical differences were ineptly smoothed over rather than forced into resolution. So while Mary steadfastly refused to ratify the Acts of Parliament that installed the new Confession of Faith, the split from the papacy and the forbidding of Mass, she manoeuvred strategically, deciding not to interfere with the new religious polity as long as she was allowed to worship freely in the Roman faith. She signed through a deal by which the new Kirk would receive one sixth of the wealth of the old Church. She crushed one of the leading Roman Catholic noblemen, the Earl of Huntly. And she took as her chief counsellor her half-brother Lord James Stewart, leader of the Lords of the Congregation, whom she created Earl of Moray in February 1562; it was through Moray and her Secretary of State, William Maitland of Lethington, that she ruled the country.

This compromise state of affairs was horribly precarious, and Mary’s plans for marriage would ultimately blow it down. After negotiations to marry Elizabeth of England’s dashing young favourite Robert Dudley foundered, Mary’s eyes turned to the young Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. It seemed a popular choice. Henry was a Scot, son of Matthew Stuart, Earl of Lennox, whom Mary had recalled from exile the previous year. For Mary, Henry’s personal charms were matched by his strategic importance in her political future, for the Lennoxes had a strong claim to the English throne. But Henry was suspected of being a Catholic; in April 1565, Moray left the court in protest, and a month later refused to give Mary a written promise that he would support the marriage, saying that he feared that Henry would not be ‘a favourer or setter forth of Christ’s true religion’; in reply, Mary gave him ‘many sore words’.

6

Soon Moray entered into a ‘band’ of mutual support with the ex-Regent Arran, head of the Hamiltons and the heir apparent to the throne if Mary failed to produce a child. At Moray’s suggestion, Arran declined a summons to court: Mary promptly proclaimed him a traitor, and only spared his life because he agreed to a five-year banishment.

7