The Crimean War (73 page)

Authors: Orlando Figes

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Other, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Crimean War; 1853-1856

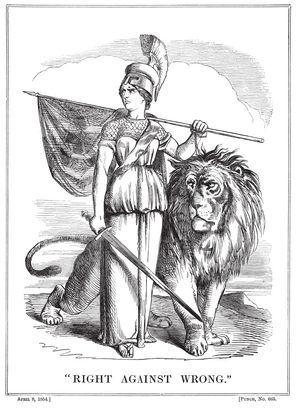

The Crimean War left a deep impression on the English national identity. To schoolchildren, it was an example of England standing up against the Russian Bear to defend liberty – a simple fight between Right and Might, as

Punch

portrayed it at the time. The idea of John Bull coming to the aid of the weak against tyrants and bullies became part of Britain’s essential narrative. Many of the same emotive forces that took Britain to the Crimean War were again at work when Britain went to war against the Germans in defence of ‘little Belgium’ in 1914 and Poland in 1939.

Punch

portrayed it at the time. The idea of John Bull coming to the aid of the weak against tyrants and bullies became part of Britain’s essential narrative. Many of the same emotive forces that took Britain to the Crimean War were again at work when Britain went to war against the Germans in defence of ‘little Belgium’ in 1914 and Poland in 1939.

Today, the names of Alma, Balaklava, Inkerman, Sebastopol, Cardigan and Raglan continue to inhabit the collective memory – mainly through the signs of streets and pubs. For decades after the Crimean War there was a fashion for naming girls Florence, Alma, Balaklava, and boys Inkerman. Veterans of the war took these names to every corner of the world: there is a town called Balaklava in South Australia and another in Queensland; there are Inkermans in West Virginia, South and West Australia, Queensland, Victoria and New South Wales in Australia, as well as Gloucester County, Canada; there are Sebastopols in California, Ontario, New South Wales and Victoria, and a Mount Sebastopol in New Zealand; there are four towns called Alma in Wisconsin, one in Colorado, two in Arkansas, and ten others in the United States; four Almas and a lake with the same name name in Canada; two towns called Alma in Australia, and a river by that name in New Zealand.

‘Right Against Wrong’ (

Punch

, 8 April 1854)

Punch

, 8 April 1854)

In France, too, the names of the Crimea are found everywhere, reminders of a war in which 310,000 Frenchmen were involved. One in three did not return home. Paris has an Alma Bridge, built in 1856 and rebuilt in the 1970s, which is now mainly famous for the scene of Princess Diana’s fatal car crash in 1997. Until then it was better known for its Zouave statue (the only one of four to be kept from the old bridge) by which water levels are still measured by Parisians (the river is declared unnavigable when the water passes the Zouave’s knees). Paris has a place de l’Alma, and a boulevard de Sébastopol, both with metro stations by those names. There is a whole suburb in the south of Paris, originally built as a separate town, with the name of Malakoff (Malakhov). Initially called ‘New California’, Malakoff was developed in the decade after the Crimean War on cheap quarry land in the Vanves valley by Alexandre Chauvelot, the most successful of the property developers in nineteenth-century France. Chauvelot cashed in on the brief French craze for commemorating the Crimean victory by building pleasure-gardens in the new suburb to increase its appeal to artisans and workers from the overcrowded centre of Paris. The main attraction of the gardens was the Malakoff Tower, a castle built in the image of the Russian bastion, set in a theme-park of ditches, hills, redoubts and grottoes, along with a bandstand and an outside theatre, where huge crowds gathered to watch the reenactments of Crimean battles or take in other entertainments in the summer months. It was with the imprimatur of Napoleon that New California was renamed Malakoff, in honour of his regime’s first great military victory, in 1858. Developed as private building plots, the suburb grew rapidly during the 1860s. But after the defeat of France by Prussia in 1870, the Malakoff Tower was destroyed on the orders of the Mayor of Vanves, who thought it was a cruel reminder of a more glorious past.

Malakoff towers were built in towns and villages throughout provincial France. Many of them survive to this day. There are Malakoff towers in Sivry-Courtry (Seine-et-Marne), Toury-Lurcy (Nièvre), Sermizelles (Yonne), Nantes and Saint-Arnaud-Montrond (Cher), as well as in Belgium (at Dison and Hasard-Cheratte near Liège), Luxembourg and Germany (Cologne, Bochum and Hanover), Algeria (Oran and Algiers) and Recife in Brazil, a city colonized by the French after the Crimean War. In France itself, nearly every town has its rue Malakoff. The French have given the name of Malakoff to public squares and parks, hotels, restaurants, cheeses, champagnes, roses and

chansons

.

chansons

.

But despite these allusions, the war left much less of a trace on the French national consciousness than it did on the British. The memory of the Crimean War in France was soon overshadowed by the war in Italy against the Austrians (1859), the French expedition to Mexico (1862–6) and, above all, the defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. Today the Crimean War is little known in France. It is a ‘forgotten war’.

In Italy and Turkey, as in France, the Crimean War was eclipsed by later wars and quickly dropped out of the nationalist myths and narratives that came to dominate the way these countries reconstructed their nineteenth-century history.

In Italy, there are very few landmarks to remind Italians of their country’s part in the Crimean War. Even in Piedmont, where one might expect to see the war remembered, there is very little to commemorate the 2,166 soldiers who were killed in the fighting or died from disease, according to official statistics, though the actual number was almost certainly higher. In Turin, there is a Corso Sebastopoli and a Via Cernaia, in memory of the only major battle in which the Italians took part. The nationalist painter Gerolamo Induno, who went with the Sardinian troops to the Crimea and made many sketches of the fighting there, painted several battle scenes on his return in 1855, including

The Battle of the Chernaia

, commissioned by Victor Emmanuel II, and

The Capture of the Malakoff Tower

, both of which excited patriotic sentiment for a few years in northern Italy. But the war of 1859 and everything that happened afterwards – the Garibaldi expedition to the south, the conquest of Naples, the annexation of Venetia from the Austrians during the war of 1866 and the final unification of Italy with the capture of Rome in 1870 – soon overshadowed the Crimean War. These were the defining events of the Risorgimento, the popular ‘resurrection’ of the nation, by which Italians would come to see the making of modern Italy. As a foreign war led by Piedmont and Cavour, a problematic figure for the populist interpretation of the Risorgimento, the campaign in the Crimea had no great claim for commemoration by Italian nationalists. There were no public demonstrations for the war, no volunteer movements, no great victories or glorious defeats in the Crimea.

The Battle of the Chernaia

, commissioned by Victor Emmanuel II, and

The Capture of the Malakoff Tower

, both of which excited patriotic sentiment for a few years in northern Italy. But the war of 1859 and everything that happened afterwards – the Garibaldi expedition to the south, the conquest of Naples, the annexation of Venetia from the Austrians during the war of 1866 and the final unification of Italy with the capture of Rome in 1870 – soon overshadowed the Crimean War. These were the defining events of the Risorgimento, the popular ‘resurrection’ of the nation, by which Italians would come to see the making of modern Italy. As a foreign war led by Piedmont and Cavour, a problematic figure for the populist interpretation of the Risorgimento, the campaign in the Crimea had no great claim for commemoration by Italian nationalists. There were no public demonstrations for the war, no volunteer movements, no great victories or glorious defeats in the Crimea.

In Turkey the Crimean War has been not so much forgotten as obliterated from the nation’s historical memory, even though it was there that the war began and Turkish casualties were as many as 120,000 soldiers, almost half the troops involved, according to official statistics. In Istanbul, there are monuments to the allied soldiers who fought in the war, but none to the Turks. Until very recently the war was almost totally ignored by Turkish historiography. It did not fit the nationalist version of Turkish history, and fell between the earlier ‘golden age’ of the Ottoman Empire and the later history of Atatürk and the birth of the modern Turkish state. Indeed, if anything, despite its victorious conclusion for the Turks, the war has come to be seen as a shameful period in Ottoman history, a turning point in the decline of the empire, when the state fell into massive debt and became dependent on the Western powers, who turned out to be false friends. History textbooks in most Turkish schools charge the decline of Islamic traditions to the growing intervention of the West in Turkey as a result of the Crimean War.

21

So do the official Turkish military histories, like this one, published by the General Staff in 1981, which contains this characteristic conclusion, reflecting many aspects of the deep resentments nationalists and Muslims in Turkey feel towards the West:

21

So do the official Turkish military histories, like this one, published by the General Staff in 1981, which contains this characteristic conclusion, reflecting many aspects of the deep resentments nationalists and Muslims in Turkey feel towards the West:

During the Crimean War Turkey had almost no real friends in the outside world. Those who appeared to be our friends were not real friends … In this war Turkey lost its treasury. For the first time it became indebted to Europe. Even worse, by participating in this war with Western allies, thousands of foreign soldiers and civilians were able to see closely the most secret places and shortcomings of Turkey … Another negative effect of the war was that some semi-intellectual circles of Turkish society came to admire Western fashions and values, losing their identity. The city of Istanbul, with its hospitals, schools and military buildings, was put at the disposal of the allied commanders, but the Western armies allowed historic buildings to catch fire through their carelessness … The Turkish people showed their traditional hospitality and opened their seaside villas to the allied commanders, but the Western soldiers did not show the same respect to the Turkish people or to Turkish graves. The allies prevented Turkish troops from landing on the shores of the Caucasus [to support Shamil’s war against the Russians] because this was against their national interests. In sum, Turkish soldiers showed every sign of selflessness and shed their blood on all the fronts of the Crimean War, but our Western allies took all the glory for themselves.

22

The effect of the war in Britain was matched only by its impact in Russia, where the events played a significant role in shaping the national identity. But that role was contradictory. The war was of course experienced as a terrible humiliation, inflaming profound feelings of resentment against the West for siding with the Turks. But it also fuelled a sense of national pride in the defenders of Sevastopol, a feeling that the sacrifices they made and the Christian motives for which they had fought had turned their defeat into a moral victory. The idea was articulated by the Tsar in his Manifesto to the Russians on learning of the fall of Sevastopol:

The defence of Sevastopol is unprecedented in the annals of military history, and it has won the admiration not just of Russia but of all Europe. The defenders are worthy of their place among those heroes who have brought glory to our Fatherland. For eleven months the Sevastopol garrison withstood the attacks of a stronger enemy against our native land, and in every act it distinguished itself through its extraordinary bravery … Its courageous deeds will always be an inspiration to our troops, who share its belief in Providence and in the holiness of Russia’s cause. The name of Sevastopol, which has given so much blood, will be eternal, and the memory of its defenders will remain always in our hearts together with the memory of those Russian heroes who fought on the battlefields of Poltava and Borodino.

23

The heroic status of Sevastopol owed much to the influence of Tolstoy’s

Sevastopol Sketches

, which were read by almost the entire Russian literate public in 1855–6.

Sevastopol Sketches

fixed in the national imagination the idea of the city as a microcosm of that special ‘Russian’ spirit of resilience and courage which had always saved the country when it was invaded by a foreign enemy. As Tolstoy wrote in the closing passage of ‘Sevastopol in December’, composed in April 1855, at the height of the siege:

Sevastopol Sketches

, which were read by almost the entire Russian literate public in 1855–6.

Sevastopol Sketches

fixed in the national imagination the idea of the city as a microcosm of that special ‘Russian’ spirit of resilience and courage which had always saved the country when it was invaded by a foreign enemy. As Tolstoy wrote in the closing passage of ‘Sevastopol in December’, composed in April 1855, at the height of the siege:

So now you have seen the defenders of Sevastopol on the lines of defence themselves, and you retrace your steps, for some reason paying no attention now to the cannonballs and bullets that continue to whistle across your route all the way back to the demolished theatre [i.e. the city of Sevastopol], and you walk in a state of calm exaltation. The one central, reassuring conviction you have come away with is that it is quite impossible for Sevastopol ever to be taken by the enemy. Not only that: you are convinced that the strength of the Russian people cannot possibly ever falter, no matter in what part of the world it may be put to the test. This impossibility you have observed, not in that proliferation of traverses, parapets, ingeniously interwoven trenches, mines and artillery pieces of which you have understood nothing, but in the eyes, words and behaviour – that which is called the spirit – of the defenders of Sevastopol. What they do, they do so straightforwardly, with so little strain or effort, that you are convinced they must be capable of a hundred times as much … they could do anything. You realize now that the feeling which drives them has nothing in common with the vain, petty and mindless emotions you yourself have experienced, but is of an altogether different and more powerful nature; it has turned them into men capable of living with as much calm beneath a hail of cannonballs, faced with a hundred chances of death, as people who, like most of us, are faced with only one such chance, and of living in those conditions while putting up with sleeplessness, dirt and ceaseless hard labour. Men will not put up with terrible conditions like these for the sake of a cross or an honour, or because they have been threatened: there must be another, higher motivation. This motivation is a feeling that surfaces only rarely in the Russian, but lies deeply embedded in his soul – a love of his native land. Only now do the stories of the early days of the siege of Sevastopol, when there were no fortifications, no troops, when there was no physical possibility of holding the town and there was nevertheless not the slightest doubt that it would be kept from the enemy – of the days when Kornilov, that hero worthy of ancient Greece, would say as he inspected his troops: ‘We will die, men, rather than surrender Sevastopol,’ and when our Russian soldiers, unversed in phrase-mongering, would answer: ‘We will die! Hurrah!’ – only now do the stories of those days cease to be a beautiful historic legend and become a reality, a fact. You will suddenly have a clear and vivid awareness that those men you have just seen are the very same heroes who in those difficult days did not allow their spirits to sink but rather felt them rise as they joyfully prepared to die, not for the town but for their native land. Long will Russia bear the imposing traces of this epic of Sevastopol, the hero of which was the Russian people.

24

24

Other books

Unleashed (Mr. Black Series Book 1) by Penelope Marshall

Cuentos frágiles by Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera

The Primal Blueprint by Mark Sisson

Suzanne Robinson by The Legend

Damaged by Pamela Callow

Mine by Coe, Maddie

Arabella by Herries, Anne

A Murder in Thebes (Alexander the Great 2) by Paul Doherty

One Thousand Nights by Christine Pope