The CV (4 page)

Authors: Alan Sugar

‘I’m very sorry,’ I answered. ‘What would you like me to do? All I can do is apologise. I’ll write him a note; I’ll do anything you want me to do.’

‘Well, if you write him a note, we’ll call the matter closed. But I don’t want to hear any more complaints about you.’

The other guys in the office were eager to know what had happened. When I told them about the plant joke, they all put their heads in their hands. ‘You didn’t! You didn’t say that, did you? You’re a bloody nutter!’

1963 – 1967: Early career

Finally, I popped the question. It wasn’t really a blunt ‘Will you marry me?’ It was more of a discussion between us along the lines of ‘I suppose we should get married then.’ Both of us were completely committed to each other and I guess getting married and spending the rest of our lives together was something we both felt was inevitable.

We were both quite shy at the time and there was a kind of embarrassment and difficulty between us in getting it out in the open. There was certainly no going down on one knee, with a rose, in a restaurant. In fact we were going over the Stratford flyover in the minivan at the time – can you imagine? Now you must

really

be asking what the hell she saw in me.

I don’t recall Ann’s response being one of great enthusiasm. I think she said, ‘Well, I suppose so.’ Maybe my character was already starting to rub off on her!

1963 – 1967: Early career

One Friday night, I came home and I said to the family, ‘I’m going to start working for myself. I told Henson today that I’m leaving.’

Henson wasn’t actually upset. He said, ‘Fair enough, if you want to go, it’s up to you. What are you going to do?’

I said, ‘I might work for myself.’

‘Fine,’ he said. ‘But let me tell you, you haven’t got very good contacts.’ Always full of encouragement.

My father looked at me as if I were mad. ‘What do you mean,

you’re going to work for yourself?

Who is going to pay you on Friday?’

That was an expression I’ll never forget, and it really sums up his whole outlook on work and life: ‘Who is going to pay you on Friday?’

I told him that I was going to pay myself on Friday.

Fortunately, Daphne, Shirley and the two Harolds were there at the time. Being of a different generation from my mum and dad, they were smiling enthusiastically, really encouraging me. I tried to reassure my dad that the profitability of my sidelines

proved

I had nothing to lose by going it alone – and I think it sunk in.

‘So what are you going to do?’

‘Well, I’m going to get down to the Post Office and take out a hundred pounds. I’ve seen a second-hand minivan in the garage over the road for fifty quid. I’ve already made enquiries and found out that it’s eight pounds for third party, fire and theft insurance. And with the rest of the money, I’m going to buy a bit of gear to sell and get on my way.’

Shirley’s Harold pointed out to me that I needed to get a National Insurance card and buy a National Insurance stamp once a week. That was another item on my list of chores.

The following day, I sprang into action. I withdrew £100 from my Post Office account, bought the van and took out the insurance.

And then, a really nice thought from Shirley. I received a telegram on Monday, which was unusual. Normally people sent them if they were

congratulating someone on a wedding or needed to relay important news, such as a death. Shirley’s telegram said, ‘GOOD LUCK ALAN IN YOUR NEW BUSINESS.’ It’s a pity I didn’t keep it.

I set off in the minivan to Percy Street, just off Tottenham Court Road, and walked into the premises of the first supplier to A M S Trading Company, my new company. Many of the big importers in the marketplace used to name their companies after themselves, but I thought Sugar Trading wouldn’t have gone down too well, so I decided upon A M S Trading, which stood for Alan Michael Sugar.

1967 – 1980:

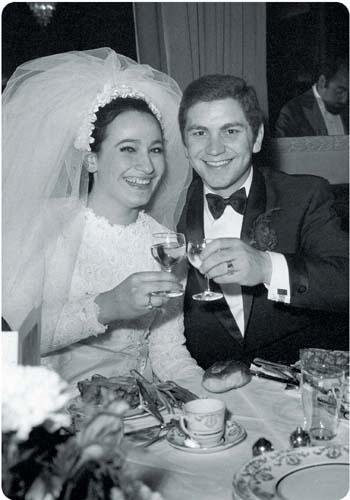

My wedding day. A memorable and wonderful occasion, but I couldn’t wait for it to be over!

1979 – 1990:

‘So, what do you want, Stanley? What have you schlapped me over here for? I’m busy. I’ve got no time for tea.’

‘Calm down, Alan. I just thought it would be nice for us to touch base.’

‘Yeah, okay, Stanley, forget all that touching base stuff and tell me what you want.’

‘Oh, you are terrible, you really are terrible, Alan. All right, well, look, let me tell you this – this Clive Sinclair fellow is going bust.’

I was shocked, but seconds after digesting the statement I remembered hearing rumours that he was running out of money fast and I’d seen a frontpage story in the

Mirror

about how the mogul Robert Maxwell was going to rescue Sinclair.

‘Right, okay . . .’ I said cautiously.

‘Well, we sell hundreds of thousands of his products and we’ve been approached by Price Waterhouse to see whether we would take over his company to get him out of trouble. Now as you know, Alan, we are retailers. We’re not interested in this, so I’m giving you the heads-up. You need to jump in quickly and see if you can sort a deal out.’

Wow! Now that

was

interesting. It actually took the wind out of my sails.

First of all, I couldn’t help feeling some satisfaction that my arch-competitor was going down the pan. I know it’s not a nice thing to say, but I’m being honest. Secondly, the acquisition of the Sinclair brand would be a massive coup for Amstrad.

After further discussion with Mark and Stanley, the story became clearer. The truth of the matter was that the man at Price Waterhouse had

not

suggested that Dixons buy the company, but had actually asked for an introduction to me, knowing that I was also a supplier to Dixons.

Dixons quite selfishly realised that if Sinclair went bust, they would be stuffed in two ways. One, they would lose a lot of business because they were selling hundreds of thousands of Sinclair Spectrums; and two, they would

have no after-sales service path for the millions of Sinclair units they’d put into the marketplace.

From Stanley’s suite in the Mandarin Hotel, we called London to speak to the guy at Price Waterhouse. From what I could gather, Sinclair was in dire financial straits. Barclays Bank had a debenture over the company and by 31 March 1986 either Sinclair had to cough up the money they owed them or they were going to force them into administration.

Clive Sinclair at that time was a national treasure and the guy at Price Waterhouse explained to me that there were deep political connotations here. They could not allow Sinclair to go into bankruptcy – it would be deemed a disaster for the flag-bearer of the British computer industry to go under. So many songs had been sung about his enterprises and Barclays Bank would be seen to be the people that shot Bambi’s mum. It’s true to say that if Clive Sinclair, who by then had been knighted, wasn’t as famous or popular as he was, the company would have simply been slung into liquidation and no one would have heard any more about it.

I agreed to call the guy from Price Waterhouse back in a couple of hours as I didn’t want to discuss my business affairs in front of Stanley and Mark. On my second call with the chap, it became clear to me there was a deal to be done. I discussed this with Bob Watkins, who was very excited at the prospect and understood what a blockbusting event this would be.

Now, here is where I defied all business logic. With no deal done, I decided there and then – before meeting Clive Sinclair or discussing numbers with banks – that I was going to buy the Sinclair business one way or another.

1979 – 1990:

‘Who on Earth Is Rupert Murdoch?’

When You See a Satellite Dish, Think of Sugar

1988–90

‘Alan, I’ve got Rupert Murdoch on the phone,’ my secretary Frances said. ‘Can I put him through?’

‘Nah, not really. Tell him I’m not in – do the usual,’ I said.

About five minutes later, she walked into my office and asked, ‘Do you know who Rupert Murdoch is?’

‘No, who is he?’

‘He’s the man who owns the

Sun

and

The Times.

He’s the man who had that trouble down in Wapping with the strikes and all that.’

It suddenly dawned on me that I hadn’t bothered to pick up the phone to speak to one of the world’s biggest media moguls. I was totally cocooned in my own little world – I knew everybody’s names in the electronics business, but I couldn’t tell you the names of any government ministers, pop stars or other celebrities.

‘Okay, Frances, get him on the phone straightaway.’

Rupert told me that my company had been recommended to him and he wanted to come and talk to me about the possibility of launching a satellite TV service in England. He’d heard that at one stage Amstrad had joined Granada and Virgin in a consortium to bid for the right to put up a satellite TV service known as BSB. He was right – we

had

done that. However, when I got the measure of some of the people in this consortium, and their lack of ideas, I decided I was no longer going to play. Richard Branson followed shortly afterwards.

Murdoch’s idea was to broadcast sixteen additional TV channels in the UK via a satellite launched by the company Astra. In those days, only four television channels existed: BBC1, BBC2, ITV and Channel 4. When I heard

his idea, I knew immediately it would be a great consumer product – the punters would go bananas for an extra sixteen channels if it could be done cheaply.

We agreed to meet and Rupert was driven from Wapping all the way to my headquarters in Brentwood. To be fair, he told me straightaway that he had done the rounds – he’d gone to the likes of Sony, Philips and even GEC, but no one was prepared to make any decisions unless he was willing to lay out a lot of money for development.

Lord Weinstock, the chairman of GEC, told him, ‘Go and see Sugar, he’s the man who can bring a consumer electronics product to the market faster than anyone else. In fact, while Sony and Philips are still thinking about it, he will have them in the market for you.’ Those are the very words Rupert told me he’d heard from Lord Weinstock.

The proposition I put to him was this: ‘If you, Mr Murdoch, provide sixteen channels of additional television, including movie channels, news and sports, I will find a way of making satellite receiving equipment so that it can be sold in places like Dixons for a hundred and ninety-nine quid.’ It was my opinion that if we could achieve this, the whole thing would work. In fact, I told Rupert I was so confident about this that he didn’t need to underwrite any orders. If he would agree to press the button on renting the space on the satellite and putting up the sixteen channels, I would be prepared to start development and production at my own risk. There was no official agreement, just a handshake. His transmission date was February 1989 –

my

job was to make sure that we had equipment in the marketplace by then.

It was now June 1988, so we had eight months to do it. Rupert called a press conference and asked me to attend. It was a massive bash held in the BAFTA auditorium in Piccadilly. After promising to launch Sky Television by February 1989, he turned to the audience and said, ‘And this man here is going to make the equipment to receive the broadcasts – and it’s going to be available for a hundred and ninety-nine quid! The proposition is, ladies and gentlemen, sixteen more channels of television for a hundred and ninety-nine quid.’

I started to feel a bit nervous, sitting there in front of the world’s media, smiling as if to say, ‘Yes, that’s right.’ Little did Rupert know that we didn’t have a bleedin’ clue how to make them yet – it was just my gut instinct that we could do it. I didn’t realise what I’d let myself in for.

1990 – 1999: