The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography (41 page)

Read The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography Online

Authors: Alejandro Jodorowsky

Tags: #Autobiography/Arts

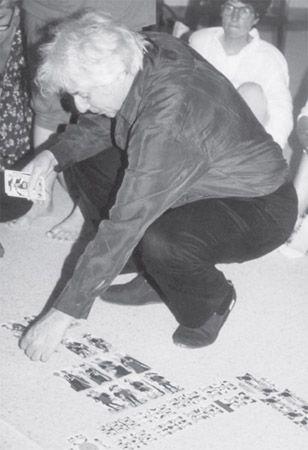

In a seminar in France, working with the minor arcana of the Tarot.

The patient must make peace with her subconscious, not becoming independent of it but making it an ally. If we learn its language, we can put it to work for us. If the family within us, rooted in childhood memory, is the basis of our subconscious, then we must develop each relative as an archetype. We must ascribe our level of consciousness to it, exalt it, imagine it reaching its highest potential. Everything we give it, we are giving to ourselves. When we deny it, we deny ourselves. As for toxic people, we should transform them by saying, “This is what they did to me, this is what I felt, this is what the abuse causes in me today, this is the reparation I desire.” Then, still within ourselves, we must bring all the relatives and ancestors to their fulfillment. A Zen master once said, “Buddha nature is also in a dog.” This means that we must imagine the perfection of every person in our family. Does someone have a heart full of bitterness, a brain clouded by prejudice, deviant sexuality due to moral abuses? Like a shepherd with his sheep we must guide them to the good path, cleansing them of their poisonous needs, desires, emotions, and thoughts. A tree is judged by its fruits, so if the fruit is bitter the tree it came from, even if it is majestic, is considered bad. If the fruit is sweet, the crooked tree it comes from is considered good. Our family—past, present, and future—is the tree. We are the fruit that gives it its value.

As my clients increased in number, on some weekends I had to receive them in groups. To heal a family, I organized a dramatization of it. The person whose family was being studied would choose from among the participants, picking those who would represent her parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts, brothers, and sisters. Then she would situate them, standing, seated on chairs, or lying down (for the chronically ill or dead), at various distances from each other, according to the logic of her family tree. Who was the hero of the family, the most powerful person? Which people were absent or despised? Which people were joined together and by what sort of ties? And so forth. Then the patient would situate herself. Where? At the center, on the edge, or removed from all of them? How did she feel there? Then, she had to confront each “actor.” Representing the family in this way, as a living sculpture, the seeker discovers that the people she has “randomly” chosen correspond in many aspects to the real people in her family and have important things to say to her. This produces a conversation that generally ends in intense embraces and tears.

These exercises leave us convinced that, having become conscious of these unhealthy relationships, we are now cured. However, once we return from the therapeutic situation into the real world, the painful symptoms are still there as always. Merely identifying a difficulty is not enough to overcome it! A gain in awareness, a theatrical confrontation, and an imagined forgiving end up being fruitless when not followed up by action in daily life. I concluded that I should induce people to act in the midst of what they conceived as their reality. But I was reluctant to do so. What right did I have to intrude in the lives of others, exerting an influence that could easily degenerate into a power grab, establishing dependencies? I was in a difficult position, considering that the people who came to see me were, in a way, asking me to become their father, mother, son, husband, wife . . . I decided to induce them to act in order for the gaining of consciousness to be effective. I did not call these people my patients, but my clients. I prescribed very specific actions, without assuming responsibility or taking on the role of their guide over their entire lives. Thus was born the psychomagical act, combining all the influences I had assimilated during the years described in the preceding chapters.

First, the person would agree to carry out the act exactly as I prescribed it, without one iota of change. To prevent distortions due to failures of memory, the client had to immediately write down the procedure to follow. Once the act was carried out they were to send me a letter that first described the instructions received, then related in full detail the way in which the act was carried out as well as the circumstances and incidents that occurred in the process. Lastly, the results should be described. Some people waited a year to send me the letter. Others argued, not wanting to do exactly what I recommended, bargaining and finding all manner of excuses to avoid following the instructions precisely.

As I observed with Pachita, when you change something, however minimally, and do not respect the indispensable conditions for the achievement of the act, the effects will be null or negative. Indeed, most of the problems we have, we want to have. We are attached to our problems. They form our identity. We define ourselves through them. It is no wonder, then, that some people try to distort the act and try to devise ways to sabotage it: getting free of problems involves radically changing our relationship with ourselves and with the past. People want to stop suffering, but are not willing to pay the price—namely, to change, to not keep living as a function of their beloved problems. For all these reasons, the responsibility of prescribing an act that must be carried out to the letter was immense. In the moment of prescribing it I had to cease identifying with myself so that I could go into a kind of trance, stop talking with my subconscious, and connect directly with the subconscious of my client. I concentrated on the mere act of giving, alleviating pain, prescribing actions that were similar to lucid dreams, without worrying about the personal benefit that would accrue to me. In order to be in a condition to heal someone, you must not expect anything from that person; you must enter all the aspects of his or her inner self without becoming involved or destabilized.

In

The Book of Five Rings

the swordsman Miyamoto Musashi recommends going to the ring early, before a fight, and acquiring a perfect knowledge of it. Likewise, familiarity with the client’s psychoaffective terrain seemed to me a fundamental requirement for the recommendation of any act, so before anything else I would ask them to tell me about their problem in as much detail as possible. Rather than trying to guess what the Tarot might be hiding from me, I would put the person through an intense interrogation. I would ask about his or her birth, parents, uncles and aunts, grandparents, siblings, sex life, relationship with money, social complexes, beliefs, love life, health, guilty feelings. (Often enough, this resembles a church confession.) Terrible secrets would emerge. One man confessed to me that as a child, at the end of the school year, he had waited on top of a wall for a hated teacher to pass and had thrown a large stone at his head. He thought that the teacher had died, but fled without checking. For thirty years, he felt like a murderer. Another time I met with a Belgian father. I perceived that he was gay. “Yes,” he confessed, “and I do it with ten men a day, in the saunas, every time I come to Paris. Do you know what my problem is? I’d like to do it with fourteen of them, like a friend of mine does!” From people who seemed normal, I heard the darkest and most outlandish secrets. One woman confessed to me that the father of her daughter was none other than her own father; a Swiss teenager, seduced by his mother, told me all the details. What most disturbed him was her jealousy, because she would not let him have any girlfriends. Because they did not perceive any criticism in me, people vented with confidence. If the therapist judges in the name of some morality, he does not cure. The attitude of the confessor must be amoral. Otherwise, the secrets never come to light. I am reminded of a Buddhist story.

Two monks are meditating in the midst of nature; several rabbits surround one monk, but none come near the other. The latter asks, “If we both meditate with equal intensity the same number of hours each day, why do the rabbits surround you and not me?”

“Very simple,” replies the other, “Because I do not eat rabbit, and you do.”

A participant in one of my courses could not bear for her chest to be touched. As soon as a man, even one with whom she wanted to have sexual relations, made a move to touch her breasts, she would start screaming. This situation caused her much suffering, and she longed to be free from this senseless panic. I suggested that she bare her chest. She did so, revealing a nice pair of breasts. I asked, “Do you trust me?”

“Yes,” she replied.

“I would like to touch you in a particular way, not like the caress of a desiring man eager to enjoy your body, nor like the touch of a doctor who examines you coldly. I would like to touch you with my spirit. Do you think my spirit could establish an intimate contact with your breasts that does not have anything sexual about it?”

“Maybe . . .”

I raised my hands, three meters away, and said gently, “Look at my hands. I’m going to approach slowly, millimeter by millimeter. As soon as you feel assaulted or uncomfortable, tell me to stop and I will stop approaching.”

I then brought my hands closer, extremely slowly. When I was ten centimeters from her breasts, she asked me to stop. I obeyed, and after a long while, slowly, very slowly, I started moving closer, watching for her reaction. Reassured by the quality of the attention I was paying to her and perceiving that I acted with delicacy and detachment, she did not protest. Finally my hands rested on her breasts without her feeling any discomfort, which caused her great amazement. Applying what I had learned from the man who fed the sparrows, I took another participant by the shoulder and, without letting go of him, had him touch her breasts as well. This caused her no suffering. But when I let go of the man, she started screaming . . . This story is an example of the detachment that, in my view, is indispensable for those who really want to help others. I was able to touch and feel the breasts of a woman standing before me while situating myself far away from my sexual center, without thinking of getting pleasure. In that moment I was not a man, but a being. The important thing is to place oneself in an inner state that excludes any temptation to take advantage of the other person, any temptation to abuse the fascination one exerts over the other in order to assert one’s power to dominate his or her will. If these things happen, the helping relationship loses its essence and becomes a masquerade.

For a magical act to have good results the popular charlatan must, by obligation, present himself as a superior being who knows all mysteries. The patient, in a superstitious manner, accepts his advice without understanding how or why it affects his or her subconscious. By contrast, the psychomagician presents himself only as a technical expert, as an instructor, and devotes himself to explaining to the patient the symbolic meaning and purpose of every act. The client knows what he or she is doing. All superstition has been eliminated. However, as soon as one begins to perform the prescribed acts, reality begins dancing in a new way. Unexpected things happen that aid in the accomplishment of something that seems impossible. For example, with an elementary school teacher who had been badly abused in childhood and was afflicted by chronic sadness I advised, among other things, learning to balance on a tightrope as circus performers do. “Impossible!” he said. “I live in a small village in the south of France. Where will I find someone to teach me that?” I insisted that he do what I proposed. Upon returning to school, one of his students told him that he was learning to balance on a tightrope from a retired circus performer who lived just a few kilometers away!

On another occasion, with a patient who had suicidal tendencies and felt that his blood was impure because he was the product of incest, I advised that he go to a slaughterhouse with two large thermoses, buy cow’s blood to fill them with, go home, and shower in the blood until all his skin was entirely covered in order to make his subconscious think that his blood had been replaced. Then, without washing off the blood, he should get dressed and go walking in the streets, proudly facing the stares of passersby. He also said, “Impossible.” However, when he went to the dentist, he found a copy of

The Incal

in the waiting room. He asked the dentist if he had read it. The dentist said no, one of his patients had left it there, a man who owned a slaughterhouse and admired my work. My client got the man’s address, went to him with some autographed copies of my works, and the slaughterhouse owner, very pleased, gave him all the liters of cow’s blood he needed.

One day I received a visit from a Swiss woman whose father had died in Peru when she was eight years old. Her mother had made all traces of the man disappear, burning letters and photos, so that my client remained an eight-year-old child on the emotional plane. I prescribed an act: she should go to Peru and visit the places where her father had lived, until she found tangible proof of his existence. When she returned to Europe she should bury the mementos in her garden and plant a fruit tree there, then go to her mother’s house and slap her. It should be explained here that her mother was an angry and virile woman who had mistreated and insulted her. The woman went to Peru, found the rooming house where her father had lived, and through that synchronicity that I call the dance of reality, found letters and photos. The father had entrusted them to the landlady, confident that one day his daughter would go to look for them. When she read those letters and saw those pictures, she no longer saw her father as a faceless ghost and finally knew that he had been a being of flesh and blood. By burying the documents in her garden, she also buried the eight-year-old child. Then she went to see her mother with the intention of giving her the prescribed slap. But she was surprised to find that for the first time her mother was waiting for her at the train station and, also, for the first time, had prepared a meal for her. Seeing her so kind, she felt very disturbed at having to slap her because, for once, her mother had given her no pretext for doing so. But she knew that the act was an inescapable psychomagical contract that must be respected. Over dessert, my client slapped her mother for no apparent reason, taking her by surprise, and feared a brutal reaction from her. But her mother only asked, “Why did you do that?” Faced with such equanimity, the daughter finally found words to express every complaint she had of her. The mother replied, “You’ve given me one slap . . . well, you should give me many more!”