The Dangerous Book of Heroes (40 page)

Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

In August 1791 the

Pandora

ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef and sank. Thirty-one crew and four of the mutineers drowned. Captain Edwards and ninety-eight survivors sailed four boats eleven hundred miles to Coupang, the second open-boat voyage to Timor for Hayward and Hallett. From there, they were repatriated via Batavia and Cape Town.

Meanwhile, the Admiralty had appointed Bligh captain to the frigate

Providence,

and with the brig

Assistant,

he was sent to Otaheite to complete his original task of transplanting breadfruit to the West Indies. On that occasion, the Admiralty appointed commissioned officers and marines. Interestingly, four

Bounty

crewâPeckover, Lebogue, Smith, and Samuelâvolunteered to sail with Bligh. He took all except Peckover. Bligh stated he didn't want to sail with any

Bounty

warrant officer ever again.

In April 1792 they arrived at Otaheite, where Bligh was welcomed by King Tynah. He met Heywood's Tahitian wife and the children of other mutineers. Disagreeable changes in Tahitian life were noted by Bligh and othersâparticularly swearingâthe effects of the mutineers having lived there for more than a year.

At Portsmouth the surviving ten of the

Bounty

's recaptured crew were court-martialed for mutiny in September 1792. The four loyal menâColeman, Norman, McIntosh, and Byrneâwere honorably acquitted. Bligh, as he had promised, had registered their innocence with the Admiralty.

Peter Heywood, Morrison, Burkitt, Muspratt, Millward, and Ellison were all found guilty and sentenced to death. Muspratt was discharged on a legal technicality and pardoned. Heywood was given a royal pardon, possibly because he was young, but probably because of his family's naval connections. Morrison was pardoned because he had not actively supported the mutiny. Three were hanged.

Â

Far away, on Pitcairn Island, the murders began. Williams's wife died, and he demanded one of the Tahitians' wives instead. The Tahitian men were furious. They rebelled and in one day murdered Williams, Christian, Mills, Martin, and Brown. They then fought one

another, and the survivors of those murders were murdered in turn by the four surviving mutineers and their Tahitian wives. McCoy committed suicide. In 1799, Quintal was murdered by Young and Adams, and Young died of asthma in 1800, leaving Adams the sole survivor.

Â

Fletcher Christian was identified by both loyal and mutinous crew as leader of the mutiny. Peter Heywood had been tried and found guilty of mutiny. Despite his later pardon, not one loyal man or mutineer had said Heywood was not part of the mutiny. As a result, the only avenue for the Christian and Heywood families to salvage their reputations was to find an acceptable reason for the mutiny. The only way to do that was to blame the

Bounty

's captain. So began the slander of William Bligh.

In a letter dated November 5, 1792, the pardoned Peter Heywood wrote to the Christians and offered to provide evidence of “false reports of slander” against Christian by one whose “ill report is his greatest praise” (Bligh). The vilification of Bligh began, with inventions of floggings, gagging, maltreatment, and sadistic cruelty.

Morrison's journal was rewritten to include accounts of cruelty, though Sir Joseph Banks stopped its publication. The Christians arranged a private “inquiry” into the mutiny by their friends, then published its “verdict” as well as a fictional appendix to the courts-martial, containing inventions of cruelty by Bligh. They altered dates, names, sequences, and facts to support the lies. When Bligh returned home, he rebutted the “appendix” but ignored most of the libelous stories about him. Some of his shipmates would not.

One, who had been with Bligh and Christian on the

Britannia,

wrote: “When we got to sea and I saw your partiality for the young man, I gave him every advice and information in my power. Though he went about every point of duty with a degree of indifference that to me was truly unpleasant; but you were blind to his faultsâ¦. In the Appendix it is said that Mr. Fletcher Christian had no attachment among the women of Otaheite; if that was the case he must have been much altered since he was with you in

Britannia,

he was

then one of the most foolish young men I ever knew in regard to the sex.”

If Christian had no attachment with the women of Otaheite, how did he contract venereal disease? Before Otaheite, Bligh had his surgeons inspect the men of the

Bounty

for VD and found none. Before the mutiny, Bligh reported that Christian's hands were sweating badly and affected everything he touched. Heywood's family admitted that Christian “was a man of violent temper,” and Rosalind Young, mutineer descendant, wrote in her 1890 history that on Pitcairn, Christian was “a violent man.”

In all the accounts written before, during, and immediately after the mutiny, in all the evidence given at all the courts-martial, there is not

one

accusation of ill treatment by Bligh and not one allegation that the mutiny was caused by cruelty. All those came later, via the Christian and Heywood families. If a reason for the mutiny must be found, it lies in the simple words of the last survivor, Adams, who said: “We only wanted to return to our loved ones on Otaheite.”

Â

William Bligh died as Vice Admiral of the Blue in 1817, having served with distinction at the battles of Camperdown (1797) and Copenhagen (1801), where he was personally commended by Admiral Nelson. In 1805 he was appointed governor of the colony of New South Wales, with specific instructions to stop the illegal rum trade in Sydney. Unfortunately, it was the New South Wales Corps under his command that organized most of the trade. The corps refused Bligh's orders, and he was faced with another rebellion. He was completely exonerated, and the officers and colonists concerned were punished.

In 1825, after both Bligh and Sir Joseph Banks had died, Peter Heywood published

Biography of Peter Heywood, Esq

. It was based upon Morrison's rewritten journal, bought from Morrison by Heywood's family. It's this biography and Morrison's doctored journal that is the source of the films, stage shows, and books portraying Bligh as an evil sadist. Some fifty films have been made about Bligh's “cruelty” causing the mutiny.

The tragedy of the Christian-Heywood slander is that it destroyed

the recognition and fame due to Admiral Bligh for his command of the 3,670-mile voyage in the

Bounty

's launch. Like his mentor, Captain Cook, he was a brilliant navigator, a brilliant seaman, a brilliant surveyor, and a humane man. The honor owed him for that voyage is long overdue. Simply, it is the greatest open-boat voyage of all time.

Recommended

A Voyage to the South Seas

by William Bligh

Mutiny of the

Bounty

and Story of Pitcairn Island 1790â1894

by Rosalind Amelia Young

The Voyage of the

Bounty'

s Launch as Related in William Bligh's Despatch to the Admiralty with the Journal of John Fryer

by William Bligh and John Fryer

The

Bounty by Caroline Alexander

Bounty

replica, Hong Kong

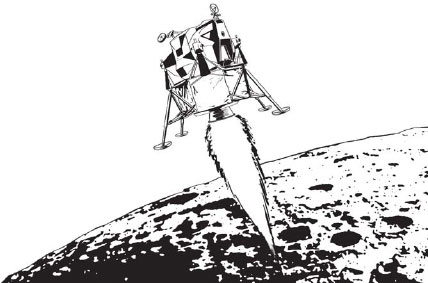

Landing on the Moon

T

he conquest of space began in October 1957, with the launch of the Soviet satellite

Sputnik 1

. It completed an orbit in ninety-six minutes at a speed of around seventeen miles per hour. In addition, it sent back information on the earth's upper atmosphere. It was a stunning achievement, and for a time the USSR threatened to have a man in space before America had launched its first satellite.

Sputnik 2

launched barely a month later, carrying the first living creature in space, a dog named Laika. There was no capacity for returning Laika to earth, and temperature and humidity increased steadily as the satellite completed its orbits. By the fourth orbit, Laika was dead; the craft burned up in the atmosphere five months later.

America's first response was a U.S. Navy satellite. In front of an audience of millions, it flamed out on the launching pad. The army took over and successfully launched a small satellite named

Explorer 1

in January 1958. It discovered the Van Allen belts, bands of radiation that surround the earth. The “space race” had begun, and

Sputnik 3

launched as early as May 1958. It was a hundred times heavier than

Explorer 1,

and the Soviets were clearly ahead.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was created as a single-purpose organization in 1958. There would be no more interservice rivalry. NASA's mission was to take on the Soviet programs and beat them. By early 1959, one-man capsules were being designed and seven astronauts were chosen. At the same time satellite launches continued, so that by 1960 America had launched eighteen and all three

Sputnik

s had been destroyed as their orbits degraded and they reentered atmosphere. For a short window of time, space was solely American. But the Soviet launches had stopped for a reason. They had set their sights on the moon.

The moon travels in an ellipse around the earth, and the distance between them varies from around 225,000 miles to over 250,000. America's first attempts to reach it showed the magnitude of the task. In August 1958,

Able 1

blew up while still in earth's atmosphere. In October,

Pioneer 1

reached a third of the way to the moon before falling back and burning up. The sheer pace of these launches seems incredible even today. The Sputnik program had rocked America. National pride was at stake, and it took another dent when the Russians successfully launched

Lunik 1

in January 1959. It reached within 5,000 miles of the moon.

The U.S.

Pioneer 4

was more successful, but then the stakes were raised again. In September 1959 the Soviet

Lunik 2

sent back photographs of the hidden side of the moon. Only a month later,

Lunik 3

successfully crash-landed on the surface, another astonishing first.

In 1960 the Apollo program was conceived with the intention of landing a man on the moon and successfully returning to earth. At the same time, the Soviet Union was training twelve cosmonauts in the race to be first. President Kennedy in America and President Khrushchev in the USSR were both committed to the task. There were no constraints on budget, only on time.

Both countries had shown that they could physically reach the moon. The two main problems remaining were engineering a “soft landing” on the surface and the even more dangerous reentry to the earth's atmosphere. Depending on where you're standing, the earth spins at around a thousand miles per hour. The friction involved in reentering that atmosphere is immense and leads to temperatures of 2,700° F, just under the melting temperature of iron. It was an era of startlingly new and astonishing challenges for mankind.

Yury Gagarin was a Russian air force pilot who had retrained as a cosmonaut. On April 12, 1961, he reached space in a Vostok three-stage launch rocket. With parachutes, he and his capsule landed separately but safely in Russian farmland. As he walked across the fields in his orange jumpsuit, a little girl asked him if he had come from space. “I certainly have,” he replied, smiling.

When he heard, the delighted Soviet premier Khrushchev said publicly: “Let the capitalist countries

try

to catch up.”

Less than a month later, Alan Shepard was the first American in space, reaching a height of 116 miles before returning. He too landed safely, and on May 25, President Kennedy gave what may be his most famous speech, saying: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth.” Never before or since has a president staked his nation's pride on so clear an objective. The Soviet Union had put the first man in space. Now it was the moon or bust.

Â

In February 1962, American John Glenn completed successful orbits in his

Friendship 7

capsule. In the same year Soviet cosmonauts spent four days in space before returning. The Apollo program kicked into high gear with a two-module spacecraft system, consisting of a command/service model that could orbit around the moon and a lunar module that could land on the surface. A three-man crew was necessary, as two men would descend to the surface and one man remain behind in the command module.

America launched a series of Gemini test flights, so named because it held two astronauts. The Soviet Union responded in 1963 by putting the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova. It was another propaganda triumph for the Soviet regime.

Space was there for the taking, and both countries launched probes to other planets as well as weather and observation satellites. In 1963, America announced a new three-man team of astronauts: Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Michael Collins. They would become the most famous men on earth. In 1964, America sent back television pictures of the hard landing of

Ranger 7

on the moon and the first television pictures of Mars. A year later a cosmonaut completed the first space walk, leaving his launch vehicle in orbit. The space age had truly begun.

In 1967 disasters struck both the American and Soviet programs.

Three astronauts died in a fire as they rehearsed an Apollo mission at Cape Kennedy. A Russian cosmonaut was killed when his capsule parachute failed, and in early 1968, Yury Gagarin died when his plane crashed.

Copyright © 2009 by Matt Haley

The Apollo tests went on, sending back television pictures of the maneuvers in earth orbit. The

Apollo 7

mission proved that the command-capsule sequence with three men could work. On Christmas Day 1968, the

Apollo 8

crew of Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders flew around the moon and returned to earth. They were the first men to see the moon up close. Frank Borman said that it was beautiful but hostile. The end of the decade was looming, and President Kennedy's promise had not yet been fulfilled. But reentry had been conquered. Only the soft landing on the moon remained.

The

Apollo 9

mission tested the docking and separation of the lunar lander in orbit, and

Apollo 10

reached the moon once more, testing the entire system in lunar orbit and looking for suitable landing sites. The team of Thomas Stafford, Eugene Cernan, and John Young had prepared the way for the final assault on the moon.

In just

twelve years,

humankind had gone from a successful satellite launch to a manned attempt at a moon landing. To put it another

way, in barely sixty years, we had gone from the first crude airplanes to the moon.

Apollo 11

was ready to launch.

Â

At sunrise on July 16, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins took their seats in

Apollo 11,

above the immense

Saturn V

rocket that would blast them out of the atmosphere. Buzz Aldrin was the last to board, but he had trained endlessly for the task ahead and was quietly confident.

To reach “escape velocity” and leave the gravity well of earth, the Â

Saturn V

rocket had to accelerate up to 24,200 miles per hour, around 7 miles per second. It is of course possible to leave earth more slowly, but only at the expense of vast amounts of fuel.

In the case of

Apollo 11,

it was similar to sitting on top of an enormous bomb. Even so, Aldrin later described the initial acceleration as so gentle that he had to check the instruments to know they were moving. They had all been in space before, on Gemini missions, but it is difficult to imagine the excitement they must have felt.

Apollo 11

reached earth's orbit in just twelve minutes. It completed one and a half orbits before a secondary engine fired and catapulted them toward the moon.

All three men looked out of the window as they left, watching the blue-green planet shrink to the size of a coin. The journey to the moon would take four days, so they ate and slept and checked the instruments, waiting for the chance to make history.

After traveling 238,587 miles, they established an orbit around the moon on July 19. Thirty orbits followed before

Apollo 11

separated into two parts:

Columbia,

which would remain in orbit with Michael Collins, and

Eagle,

the four-legged lunar lander that would take Armstrong and Al

drin to the surface. It was an incredibly light, fragile vehicle. Aldrin said he could have pushed a pencil through its walls.

Copyright © 2009 by Matt Haley

The computer had selected a landing site, but as the two men approached the surface, they realized it was too rocky. Neil Armstrong took manual control of

Eagle,

guiding it with small puffs of propellant. Aldrin called out the height from the ground as they came down as gently as possible. By the time they landed, they had only fifty seconds of fuel to spare, but they were down safely. The two men grinned at each other.

The first words spoken on the moon were actually by Buzz Aldrin, while still in the lander. He was confirming technical data with Armstrong and said: “Contact light! Okayâengine stop. ACAâout of detent.” After that Armstrong said the more famous words: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The

Eagle

has landed.” They rested and ate a meal, then began to put on their space suits to go outside.

Copyright © 2009 by Matt Haley

One lesser-known fact is that Aldrin was an elder of the Webster Presbyterian Church, and he also took communion, the first ever religious service off-planet. The chalice he used is still used to commemorate the event each year.

Neil Armstrong climbed out first, activating the cameras as he did so. He clambered down the ladder and landed gently in the one-sixth gravity of the moon. Famously, he said: “That's one small step forâ¦man, one giant leap for mankind.” Aldrin then climbed down to join him on the surface.

There is no color on the moon. Aldrin described it as “magnificent desolation.” The landscape is gray and white, and without an atmosphere, the sky is as black as the darkest night on earth. In the

distance, they could see earth hanging in the sky. For the first time in  human existence, a man standing on another world could look at the home of Einstein, Galileo, Newton, and every other man and woman who had ever lived.