The Daughter of Odren

Read The Daughter of Odren Online

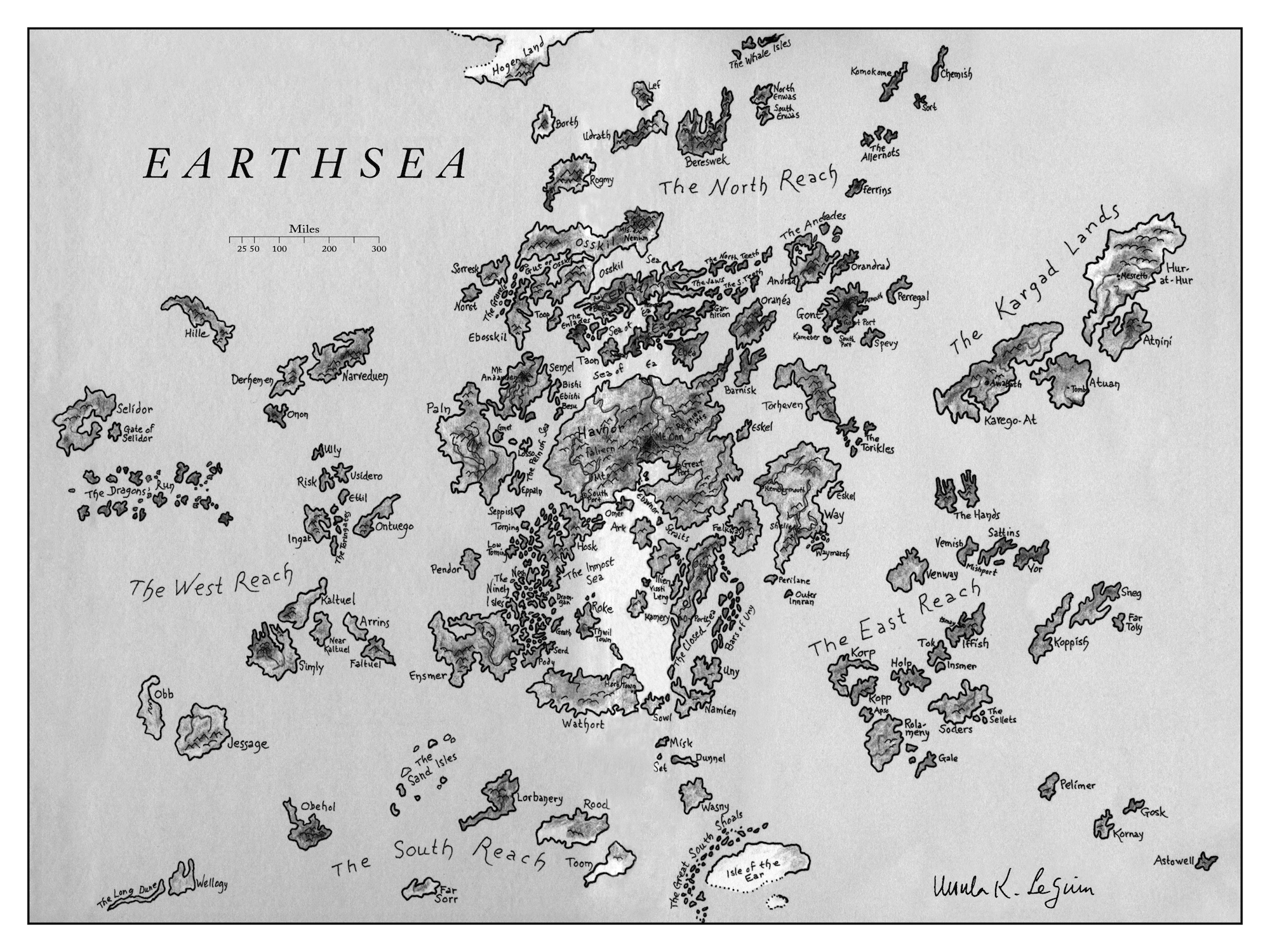

Authors: Ursula K. Le Guin

Read More from Ursula K. Le Guin

Copyright © 2014 by Ursula K. Le Guin

Cover image copyright © 2014 David Henderson/Corbis

Earthsea logo copyright © 2014 Craig Howell

Â

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Â

Â

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file.

Â

eISBN 978-0-544-35838-6

v1.1014

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

B

EFORE DAYBREAK IN LATE SUMMER

and early autumn, fog gathers on the waters of the Closed Sea, drifting up over the steep eastern coast of the Island of O, blurring away the upland fields and pastures that run out to the cliffs. Every blade of grass and frond of fern bows to a burden of waterbeads. The fog smells of salt and seaweed and smoke from the early fires of farmhouse hearths.

In the darkness before dawn, a bobbing, glowing, pallid sphere moved through the fields: the light of a candle-lantern on the fog immediately around it. Beside it was a dark blur, the skirt of the woman who carried the lantern. She moved on steadily through the fog and dark, following a path deeply foot-worn and as deeply worn into her as into the earth. She did not hesitate and did not pause until the path brought her down into a shallow valley. There, something loomed ahead of her, a bulk that caught the lantern light, a dim mass taller than herself. She came up to it: a standing stone, its rough, pitted surface pale where the lantern-light shone on it, the rest of it dark in darkness. She set down the lantern near it and the shadows changed, running up the stone. She put down the basket she carried. She went to the standing stone, bowed to it, and embraced it. She stood for some time holding it stiffly in her arms, her forehead bowed against it.

After a while she drew back from it and spoke. “Remember me,” she said in a low voice. “Remember your life. Remember your children. Think of me. I'm here. I'll never leave you. Think of yourself, what you were. You will be avenged. Be patient. Don't sleep. Never sleep. Wait.” Then she embraced it in a harder, briefer hold, and turned away.

From the basket she took a jug and reached up to pour water over the uneven top of the stone. A clay bowl lay in the weedy grass at its base, with a trace of coarse meal in it. She emptied it, rinsed it from the jug, dried it on her apron, and refilled it with a handful of meal from her basket. She set it down and laid across it a spray of flowers, blue autumn daisies, short-stemmed, half dried-up though wet with fog and dew.

Laying her hand on the stone, she whispered: “Here's food, food for your soul, for your strength. Eat, drink. Be strong. Wait. Don't sleep, Father. Wake, and wait. You will be avenged. Then you can sleep.”

Looking around and seeing the mist pale with the first daylight, she stooped and blew out the candle in the lantern. She took up the lantern and basket and turned back the way she had come. The fog whitened and seemed to thicken as it imperceptibly filled with light. She could not see more than a few steps ahead on the foot-worn, narrow track up the slope out of the shallow valley and across rough pastures, but she walked with the same unhesitating stride. The steady sound of the sea at the foot of the cliffs was loud in the valley of the standing stone but died away soon in the inland pastures, muffled by fog and earth. Sheep a little darker than the fog stared at her from close to the path, heavy with wet, their wool all full of round fog-drops. She heard their movements, the clink of bells. A ewe made a hoarse roaring blat and a half-grown lamb bleated in reply.

It was a half mile or so across the pastures to Hill Farm. The farmer was leaving for the hayfield as his wife came into the farmyard. He greeted her, his voice subdued. “Good morning, mistress.”

“Good morning, master,” she said, also speaking low. “I'll bring your lunch to the Low Meadow.”

Farmer Bay nodded. “Thanks,” he said, and trudged off into the thinning mist, a short man going grey, gnarled with muscle, shouldering his scythe. It had been a good summer for haygrass and they were cutting the Low Meadow for the second time.

After Bay's wife had seen to the house and kitchen garden

she took the smaller scythe and a basket of bread, cheese, and pickled onion and went to join her husband in the hay-meadow. The sun was hot and high in the eastern sky by then. The fog had burned off the land and withdrawn to lie in a low, dark-silver line along the east edge of the sea, hiding the islands.

As she topped the rise before she went down to the meadow the farmer's wife turned to look back at the rise and fall of the land between her and the high sea-horizon. Bay's farmhouse stood sheltered on a mild slope among old willow trees a quarter mile away. To the west of it were other farms, and south of it she could see the tallest chimney and some treetops of the village. Northward, on higher land, the groves and high slate roofs of the house of the Lords of Odren stood out clear. To her east, a fold of the hills hid the vale of the standing stone where she had been that morning and every morning for fourteen years. Her eyes knew that fold of land and what it hid, and all the lands and fields and the roads around it, and the half circle of the eastern sea beyond it all. It was a great, still scene, and she saw it all with a still heart. She was just turning to go down to the hay-meadow when her gaze became alert and fixed.

Two people were on the road that came north from the village, a whitish track meandering along among the pastures some way inland from the cliffs. At this distance the two figures were as small and black as insects. They stopped where a footpath crossed the road from inland and led out to the edge of the cliff. She watched them intently while they stood. They were apparently talking. She could see one of them making gestures, like the waving of an ant's feelers. When they went on past the footpath up the road, she watched them a moment more, then turned away and went on down to the haying.

Â

“No,” the young man said, stopping suddenly. “No, you're wrong, Hovy. It was that path. The next path off this road would be to the orchards. It has to be that one.” He set off walking much faster back down the road to the barely marked track that crossed it. A shuffle of footprints where they had stood discussing their way was clear in the white dust there. He headed resolutely inland. His companion followed him silently.

The footpath, not much used and barely visible in places, wound about through hilly pastureland and ended in a long, dry vale under dry slopes. Bay trees, willows, and a single tall cedar stood among a scatter of old gravemounds and fallen, broken marker stones. An ancient cairn of boulders piled higher than a man and half overgrown with shrubs and weeds stood in the center of the burial ground. The young man walked toward it. He stopped and stood as if bewildered, staring at the red-orange flowers of a creeper growing among the stones of the cairn. He looked at the older man who followed him.

The older man shook his head.

“This is Evro's Cairn,” the young man said, as if regaining the name, the memory. “But then where . . .”

The other man gestured northwestward, a short, small movement of his hand, as if inviting the other to precede him. He stood patiently waiting for the young man to go first, or to speak. The young man still looked bewildered and did not move, and after a minute the other set off. There was no path, but he walked as if he knew where he was going, starting up one of the slopes of short dry grass at a steady pace and crossing over it. The young man followed him, hurrying to catch up.

Both of them wore travel-dirty clothes and mended sandals. The younger man walked empty-handed; the older man had a stick in his hand, a pouch slung over his shoulder. He was in his fifties, or older, and had a worn, worried look. When they came through the fold of the hills into a narrow valley he stopped as soon as he saw the standing stone. He turned his anxious face to his companion. The young man hurried on past him, going straight to the stone.

A field mouse skittered out of the bowl of meal, scared from its daily breakfast, and vanished into the weeds at the base of the stone.

The young man stopped a few feet from the stone and straightened up to face its pale grey, blunt bulk. It stood about his own height and maybe twice his girth, a little wider than it was deep. A cleft ran up the lower part, dividing it in two, and the top of it narrowed in enough to give a faint suggestion of a head.

“The Standing Man,” Hovy whispered.

The young man nodded impatiently. He moved a little closer, reached out his right hand, and touched the stone. He drew in his breath.

“What's this?” he said, looking down at the bowl of meal and the withering branch of flowers.

“I don't know,” the other man said.

“Somebody's made an offering here, Hovy.”

In the flood of sunlight in the silent valley they stood silent, the three of them, the young man, the older man, the stone.

Â

“It's kind of you to let me rest here,” said the stranger to the innkeeper. “âIf you want dried fish, go on down to the port,' I said to 'em, âbut I'm not taking an extra step today.'” She stuck out her worn shoes with patched soles.

“On your way north, eh?”

“Our nephew that's been living with us is going back to his folk there. Might be we'll settle there too if there's work. There's none where we're from.” She gestured vaguely to the south.

“And where would they live then?” the innkeeper asked, looking up from the beans she was shelling, ready to chat. “In Riro, would it be?”

“Oh, let me give you a hand with those. I can't sit and see work done and not lend a hand. No, it's not Riro. The name of the village has just gone out of my head, but it's a great long way up the coast, I believe. I'll find out how long it is with my own feet, won't I? Paro, would that be the name of the place?”

The innkeeper shook her head, indifferent. Riro was the north end of her world.

“It's a long road is all I know! Now, these are lovely beans. Fat and sweet as little quail.”

“They'll be supper. With a bit of rabbit, or a hen if you'd rather.”

“Oh, rabbit by all means. I love a bit of stewed rabbit with raily beans. D'you call 'em railies?”

“I've heard it. Mostly we call 'em trailers.”

The guest nodded, thumbing the plump pink beans from their mottled shells into a bowl and tossing the shells into a wide basket in rhythmic alternation with her hostess.

“Now it seems I once was told a story about the great house here,” she said. “Or is it about Riro, the story I'm thinking of?”

“No,” the innkeeper said with perfect certainty. “It's about Odren.” She screwed up her long face, suppressing satisfaction. “A terrible story,” she said.

“Is it? It was to do with a sorcerer, I think? An uncanny man? Eh, I don't know if I want to hear it if it's about uncanny things. I do lie awake nights fearing things! Though what there is to fear I don't know. My man and I can hardly get poorer than we are, and what's to fear worse than starving?” She laughed her cheerful laugh, but her eyes had an anxious look in them.

The innkeeper was not diverted from her course. “Terrible it is, the story,” she said. “Uncanny, and worse than that. It was when I first came here from Endway Farm. Fourteen, fifteen years ago. The lords of Odren, they're the great folk here; they own land here and all north of here for a long way. The master of Odren, he's the master of many among us. And so. That was the time when pirates had gathered in the isles, out there.”