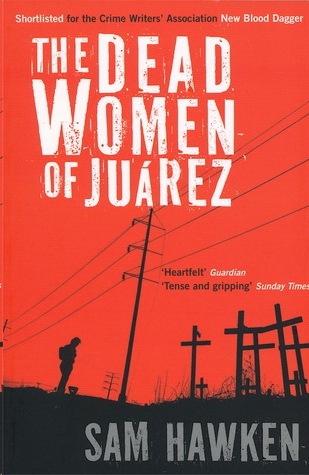

The Dead Women of Juarez

Read The Dead Women of Juarez Online

Authors: Sam Hawken

The Dead Women of Juarez (2011)

A novel by Sam Hawken

Synopsis:

In the last twenty years, over 3000 women have disappeared from Ciudad Juarez, on the border between Mexico and the USA. Sam Hawken takes this story of mass murder and abduction and weaves around it the story of Kelly Courter, a washed up boxer from Texas, who is past playing the stooge in the ring, as long as he gets paid.

A visceral crime novel based on the true story of mass murder in a Mexican border town

Sam Hawken

is a native of Texas now living on the east coast of the United States. A graduate of the University of Maryland, he pursued a career as an historian before turning to writing.

The Dead Women of Juárez

is his first novel.

Sam Hawken

For

las mujeres muertas de Juárez

Bolillo

ONE

R

OGER

K

AHN WROTE

, “B

OXING IS

smoky halls and kidneys battered until they bleed,” but in Mexico everything bled in the ring. And there was also pain.

When Kelly Courter fought in the States he was a welterweight, but he didn’t fight Stateside anymore and he was heavier. No amount of sweating and starving would take him out of the middleweight class now. This mattered little to the man who paid the purse. If pressed he would call these catchweight fights, but they were really just demolition without a weigh-in or any formality beyond money changing hands.

The Mexican kid was leaner and harder than Kelly, and that was the point; Kelly was here to be the kid’s punching bag. Mexicans liked to see La Raza get one over on a white guy. It was twice as good if the white guy came from Texas like Kelly did.

They circled. Kelly’s blood was on the canvas because he was gashed over the right eye and his nose was dripping. Vidal, the cut man working Kelly’s corner, wasn’t much for adrenaline and pressure alone couldn’t stop the leaking. The crowd wanted to see the

bolillo

bleed anyway.

Kelly worked the jab to keep the kid at a distance. He connected, but he wasn’t putting enough hurt behind the punches to make a difference to the outcome. His shoulders burned and his calves threatened to cramp. He started the match dancing, but now he was shuffling.

They traded punches. Kelly soaked up the kid’s straight right

with his cheekbone and when his head rocked he heard and felt his neck bones crackle. He hooked a punch into the kid’s ribs, but his follow-up left windmilled. And then they were apart again, circling. If Kelly could keep the action in the center of the ring, he might manage to stay on his feet through six rounds.

The bell rang. The crowd was happy. Under the ring lights a layer of tobacco smoke was as thick and gray as a veil.

Vidal wiped the blood off Kelly’s face and pressed an icy-cold enswell where it would do the most good. In the other corner, the Mexican kid’s trainer talked the boy up while he got all the best stuff, from ice packs to adrenaline hydrochloride. Kelly didn’t have a trainer with him because he wasn’t that high-class; he was just the designated sacrifice. Vidal came with a ten-year-old boy who worked the bucket and iced down Kelly’s mouthpiece. Kelly paid them both ten bucks a round.

“Can you do something about my nose?” Kelly asked Vidal after his gum shield came out. “I can’t breathe right.”

“Don’t get punched in the face no more,” Vidal replied, but he stuffed a soaking Q-tip up Kelly’s left nostril and swabbed it around. “Here, suck it up.”

Kelly snorted and his sinuses flushed with the stink of alcohol and blood. Kelly felt nauseated. The boy held up his plastic bucket. Kelly spat into it instead of throwing up.

“You going to make it?” Vidal asked.

“What round are we in?”

“You can fall down any time now. Fall down or get knocked down.”

“He can knock me down.”

“Then you’re stupid.”

The bell rang. Vidal yanked the Q-tip out of Kelly’s nose too roughly, but the bleeding didn’t start again.

As far as smokers went this one wasn’t too big: about forty men surrounded the ring and the walls were close. Everybody had something to drink and there were lots of cigars. Old Mexican faces

heavy with wrinkles and extra chins and dark eyes grew darker in the shadows of a fight so that looking out beyond the ropes a fighter saw only dozens of dead, unblinking holes.

“

¡Délo a la madre!

”

Give him to the Mother

. Roughly it meant

kick his ass to death

.

The Mexican kid came straight at Kelly and so did the first hard jab. Maybe Kelly was distracted, or maybe he was slower than he thought, but the punch came through his hands and cracked him right between the eyes. It shouldn’t have rocked him, but it did.

Kelly took a step back. A left hook took him flush and the combo right to the body made his guts shake. He had his hands up, but they weren’t where they needed to be, so the kid battered him left-right, left-right, and he fell while all the old men cheered the blood.

Back in the States the ref would step in once Kelly’s head bounced off the canvas, but this wasn’t the States. Kelly’s nose was gushing again. The Mexican kid was over him. Another punch slugged down from the heavens and blocked out the ring lights. Only then was the bell rung. The ref raised the Mexican kid’s hand and Kelly Courter disappeared for everyone in the room.

I

F THE PLACE HAD DRESSING ROOMS

,

they weren’t for

bolillos

. They set Kelly and Vidal up at the back of the men’s room. While drunken

viejos

wandered in and out to use the piss trough, Vidal helped Kelly get the tape off his fists and get changed. He cleaned up Kelly’s face the best he could, but he worked corners and wasn’t a doctor.

Green and white paint on the walls peeled from neglect and humidity. The men laughed at Kelly and insulted him in Spanish because they didn’t think he understood them, but he did. “His face looks like a bowl of

frijoles refritos

,” one of the old men said to another. Kelly might have argued, but he saw himself in a mirror coming in and knew they weren’t far wrong; the Mexican kid did a dance on his face.

Vidal put his thumbs on either side of Kelly’s nose and pressed until cartilage crunched. Needles of pain stabbed through Kelly’s forehead then and when Vidal put tape across the bridge of his nose to keep things stable. Kelly would have two black eyes for a while.

Ortíz came in. The room reeked of urine and shit. There wasn’t a breath of fresh air inside four walls. Ortíz didn’t look like the kind of man who’d wash his hands in a place like this even if the sink worked. He took a wad of American bills out of his jacket and counted out $200.

“What did you think of Federico?” Ortíz asked Kelly.

Kelly gave Vidal two twenties. The old cut man put the money away and packed up. “I think he punches hard,” Kelly said.

“Oh, yeah,” Ortíz agreed. “Without gloves on, he could kill you.”

“Then I guess I’m lucky he had gloves on.”

Outside the bathroom the crowd revved up again. Kelly’s match wasn’t the only fight on the card, but the rest of the fights were all brown on brown. Now that the spectators had their appetites whetted, good matches would go down smooth.

“You want I should call a taxi for you?” Ortíz asked.

“I don’t want to waste the money.”

“Hey, it’s on me, Kelly.”

Vidal was already out the door. Kelly got up. His bag and jacket were inside a stall with a broken toilet. Ortíz’s money went in Kelly’s pocket. “You already paid me. And I’m not fuckin’ crippled,” Kelly said. “I’ll take myself out.”

“Hey,

amigo

,” Ortíz said, “I might have something for you next month, you heal up okay. You want I should let you know?”

A month would give the cuts time to close and the bruises to fade. Every dollar in Kelly’s pocket would be gone, too. The only constant was the demand for gringo blood.

“Yeah, okay,” Kelly said, and he left.

It was hot and still light on the street. Kelly could have gone right to bed. People outside the fights — too proper to care, or too sophisticated to admit it — didn’t understand what a fighter gave up in the ring. Every drop of sweat had a cost and every punch thrown or taken did, too. Kelly was tired because he was all paid out.

He left the smoker behind. Old cars crowded the broken curb on both sides of the street. Rows of fight notices were pasted up beside the entrance. Even out here Kelly still heard the spectators hollering.

Kelly didn’t have a car, old or not. He drove a slate-gray Buick down from El Paso five years before and sold it for a hundred bucks and some Mexican mud. He was already so bent that the

culero

paid him half what he promised and Kelly didn’t notice until it was too late. So he walked, bag over his shoulder, and kept his swollen face pointed toward the pavement. Juárez had plenty of buses.

He stopped two blocks down to spend some of his money. A little bar with a jukebox playing

norteño

beckoned Kelly inside. He had six bottles of Tecate, one after the other, and that took the hurt off some. The alcohol stung a cut in his mouth. He was the only white man in the place; the rest were rough brown men who worked with their hands under the sun or with machines in the

maquiladoras

. They ignored Kelly and that was fine.

“

Oye

,” Kelly asked the bartender. “You know where I can find some

motivosa? ¿Entiende?

”

The bartender pointed. The bar was long and narrow and lit mostly with strings of big-bulb Christmas lights. Posters for the corridas, the bullfights, were on the walls beside pictures and license plates and any other junk they could put up with a nail. Booths with high backs marched all the way back to the

baños

.

Kelly checked each booth until somebody made eye contact. He put his bag in first and sat down next to it. “

Motivosa

,” he said to the woman.

“How much you looking for?” the woman asked. She was flabby and braless and wore an unflattering shell-pink top that showed too much arm and neckline.

Kelly put a couple of Ortíz’s twenties on the table between them. “Keep me busy.”

The woman took Kelly’s money and stuffed it into her shirt. From somewhere under the table she produced a shallow plastic baggie of grass. Kelly put the baggie away. “You that white boy they like to knock around at

el boxeo

, eh?” the woman asked.

“What of it?” Kelly asked.

“Next time you around, come see me.”

“What for?”

The woman smiled. She had even, white teeth. Kelly realized they were dentures. “I like

boxeadores

,” she said. “Next time you come around, I get you relaxed.”

Kelly got up. “That’s what I get the herb for.”