Read The Design of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Don Norman

The Design of Everyday Things (50 page)

Why is this? Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee quote the world-champion human chess player Gary Kasparov, explaining why “the overall winner in a recent freestyle tournament had neither the best human players nor the most powerful computers.” Kasparov described a team consisting of:

Â

a pair of amateur American chess players using three computers at the same time. Their skill at manipulating and “coaching” their computers to look very deeply into positions effectively counteracted the superior chess understanding of their grandmaster opponents and the greater computational power of other participants. Weak human + machine + better process was superior to a strong computer alone and, more remarkably, superior to a strong human + machine + inferior process

. (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2011.)

Moreover, Brynjolfsson and McAfee argue that the same pattern is found in many activities, including both business and science: “The key to winning the race is not to compete against machines but to compete with machines. Fortunately, humans are strongest exactly where computers are weak, creating a potentially beautiful partnership.”

The cognitive scientist (and anthropologist) Edwin Hutchins of the University of California, San Diego, has championed the power of distributed cognition, whereby some components are done by people (who may be distributed across time and space); other components, by our technologies. It was he who taught me how powerful this combination makes us. This provides the answer to the question: Does the new technology make us stupid? No, on the contrary, it changes the tasks we do. Just as the best chess player is a combination of human and technology, we, in combination

with technology, are smarter than ever before. As I put it in my book

Things That Make Us Smart

, the power of the unaided mind is highly overrated. It is things that make us smart.

Â

The power of the unaided mind is highly overrated. Without external aids, deep, sustained reasoning is difficult. Unaided memory, thought, and reasoning are all limited in power. Human intelligence is highly flexible and adaptive, superb at inventing procedures and objects that overcome its own limits. The real powers come from devising external aids that enhance cognitive abilities. How have we increased memory, thought and reasoning? By the invention of external aids: it is things that make us smart. Some assistance comes through cooperative, social behavior: some arises through exploitation of the information present in the environment; and some comes through the development of tools of thoughtâcognitive artifactsâthat complement abilities and strengthen mental powers

. (The opening paragraph of

Chapter 3

,

Things That Make Us Smart

, 1993.)

It is one thing to have tools that aid in writing conventional books, but quite another when we have tools that dramatically transform the book.

Why should a book comprise words and some illustrations meant to be read linearly from front to back? Why shouldn't it be composed of small sections, readable in whatever order is desired? Why shouldn't it be dynamic, with video and audio segments, perhaps changing according to who is reading it, including notes made by other readers or viewers, or incorporating the author's latest thoughts, perhaps changing even as it is being read, where the word

text

could mean anything: voice, video, images, diagrams, and words?

Some authors, especially of fiction, might still prefer the linear telling of tales, for authors are storytellers, and in stories, the order in which characters and events are introduced is important to build the suspense, keep the reader enthralled, and manage the emotional highs and lows that characterize great storytelling. But

for nonfiction, for books like this one, order is not as important. This book does not attempt to manipulate your emotions, to keep you in suspense, or to have dramatic peaks. You should be able to experience it in the order you prefer, reading items out of sequence and skipping whatever is not relevant to your needs.

Suppose this book were

interactive? If you have trouble understanding something, suppose you could click on the page and I would pop up and explain something. I tried that many years ago with three of my books, all combined into one interactive electronic book. But the attempt fell prey to the demons of product design: good ideas that appear too early will fail.

It took a lot of effort to produce that book. I worked with a large team of people from Voyager Books, flying to Santa Monica, California, for roughly a year of visits to film the excerpts and record my part. Robert Stein, the head of Voyager, assembled a talented team of editors, producers, videographers, interactive designers, and illustrators. Alas, the result was produced in a computer system called HyperCard, a clever tool developed by Apple but never really given full support. Eventually, Apple stopped supporting it and today, even though I still have copies of the original disks, they will not run on any existing machine. (And even if they could, the video resolution is very poor by today's standards.)

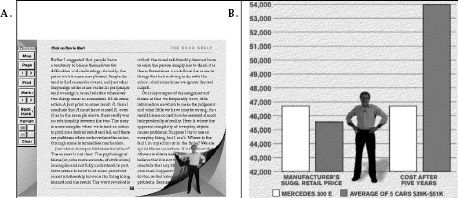

FIGURE 7.5.

Â

The Voyager Interactive Electronic Book.

Figure A

, on the left, is me stepping on to a page of

The Design of Everyday Things

.

Figure B

, on the right, shows me explaining a point about graph design in my book

Things That Make Us Smart

.

Notice the phrase “it took a lot of effort to produce that book.” I don't even remember how many people were involved, but the credits include the following: editor-producer, art directorâgraphic designer, programmer, interface designers (four people, including me), the production team (twenty-seven people), and then special thanks to seventeen people.

Yes, today anybody can record a voice or video essay. Anyone can shoot a video and do simple editing. But to produce a professional-level multimedia book of roughly three hundred pages or two hours of video (or some combination) that will be read and enjoyed by people across the world requires an immense amount of talent and a variety of skills. Amateurs can do a five-or ten-minute video, but anything beyond that requires superb editing skills. Moreover, there has to be a writer, a cameraperson, a recording person, and a lighting person. There has to be a director to coordinate these activities and to select the best approach to each scene (chapter). A skilled editor is required to piece the segments together. An electronic book on the environment, Al Gore's interactive media book

Our Choice

(2011), lists a large number of job titles for the people responsible for this one book: publishers (two people), editor, production director, production editor, and production supervisor, software architect, user interface engineer, engineer, interactive graphics, animations, graphics design, photo editor, video editors (two), videographer, music, and cover designer. What is the future of the book? Very expensive.

The advent of new technologies is making books, interactive media, and all sorts of educational and recreational material more effective and pleasurable. Each of the many tools makes creation easier. As a result, we will see a proliferation of materials. Most will be amateurish, incomplete, and somewhat incoherent. But even amateur productions can serve valuable functions in our lives, as the immense proliferation of homemade videos available on the Internet demonstrate, teaching us everything from how to cook Korean

pajeon

, repair a faucet, or understand Maxwell's equations of electromagnetic waves. But for high-quality professional material that tells a coherent story in a way that is reliable, where the

facts have been checked and the message authoritative, where the material will flow, experts are needed. The mix of technologies and tools makes quick and rough creation easier, but polished and professional level material much more difficult. The society of the future: something to look forward to with pleasure, contemplation, and dread.

The Moral Obligations of Design

That design affects society is hardly news to designers. Many take the implications of their work seriously. But the conscious manipulation of society has severe drawbacks, not the least of which is the fact that not everyone agrees on the appropriate goals. Design, therefore, takes on political significance; indeed, design philosophies vary in important ways across political systems. In Western cultures, design has reflected the capitalistic importance of the marketplace, with an emphasis on exterior features deemed to be attractive to the purchaser. In the consumer economy, taste is not the criterion in the marketing of expensive foods or drinks, usability is not the primary criterion in the marketing of home and office appliances. We are surrounded with objects of desire, not objects of use.

NEEDLESS FEATURES, NEEDLESS MODELS: GOOD FOR BUSINESS, BAD FOR THE ENVIRONMENT

In the world of consumable products, such as food and news, there is always a need for more food and news. When the product is consumed, then the customers are consumers. A never-ending cycle. In the world of services, the same applies. Someone has to cook and serve the food in a restaurant, take care of us when we are sick, do the daily transactions we all need. Services can be self-sustaining because the need is always there.

But a business that makes and sells durable goods faces a problem: As soon as everyone who wants the product has it, then there is no need for more. Sales will cease. The company will go out of business.

In the 1920s, manufacturers deliberately planned ways of making their products become obsolete (although the practice had existed

long before then). Products were built with a limited life span. Automobiles were designed to fall apart. A story tells of Henry Ford's buying scrapped Ford cars and having his engineers disassemble them to see which parts failed and which were still in good shape. Engineers assumed this was done to find the weak parts and make them stronger. Nope. Ford explained that he wanted to find the parts that were still in good shape. The company could save money if they redesigned these parts to fail at the same time as the others.

Making things fail is not the only way to sustain sales. The women's clothing industry is an example: what is fashionable this year is not next year, so women are encouraged to replace their wardrobe every season, every year. The same philosophy was soon extended to the automobile industry, where dramatic style changes on a regular basis made it obvious which people were up to date; which people were laggards, driving old-fashioned vehicles. The same is true for our smart screens, cameras, and TV sets. Even the kitchen and laundry, where appliances used to last for decades, have seen the impact of fashion. Now, out-of-date features, out-of-date styling, and even out-of-date colors entice homeowners to change. There are some gender differences. Men are not as sensitive as women to fashion in clothes, but they more than make up for the difference by their interest in the latest fashions in automobiles and other technologies.

But why purchase a new computer when the old one is functioning perfectly well? Why buy a new cooktop or refrigerator, a new phone or camera? Do we really need the ice cube dispenser in the door of the refrigerator, the display screen on the oven door, the navigation system that uses three-dimensional images? What is the cost to the environment for all the materials and energy used to manufacture the new products, to say nothing of the problems of disposing safely of the old?

Another model for sustainability is the subscription model. Do you have an electronic reading device, or music or video player? Subscribe to the service that provides articles and news, music and entertainment, video and movies. These are all consumables, so

even though the smart screen is a fixed, durable good, the subscription guarantees a steady stream of money in return for services. Of course this only works if the manufacturer of the durable good is also the provider of services. If not, what alternatives are there?

Ah, the model year: each year a new model can be introduced, just as good as the previous year's model, only claiming to be better. It always increases in power and features. Look at all the new features. How did you ever exist without them? Meanwhile, scientists, engineers, and inventors are busy developing yet newer technologies. Do you like your television? What if it were in three dimensions? With multiple channels of surround sound? With virtual goggles so you are surrounded by the images, 360 degrees' worth? Turn your head or body and see what is happening behind you. When you watch sports, you can be inside the team, experiencing the game the way the team does. Cars not only will drive themselves to make you safer, but provide lots of entertainment along the way. Video games will keep adding layers and chapters, new story lines and characters, and of course, 3-D virtual environments. Household appliances will talk to one another, telling remote households the secrets of our usage patterns.