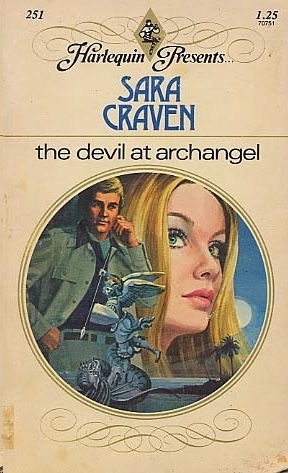

The Devil at Archangel

Read The Devil at Archangel Online

Authors: Sara Craven

THE DEVIL AT

ARCHANGEL

Sara Craven

"You must beware, mademoiselle ...." The fortune-teller's ominously

harsh voice had sent shivers down Christina's spine. "Beware of the

devil at Archangel."

The prediction seemed silly when Christina first arrived at the

Brandon's beautiful Caribbean plantation. Left without means and a

home by her godmother's death, the job at Archangel seemed like a

gift from heaven.

But everything changed when she met Devlin Brandon. He disturbed

her to the core of her being. She must indeed beware of this manor did

another devil await to torment her?

'LOT thirty-four—this fine pair of Staffordshire figures, ladies and

gentlemen. Now what am I bid for ...?'

The penetrating tones of the auctioneer were suddenly reduced to a

subdued murmur as Christina quietly closed the dining room door

behind her and began to walk slowly down the flagged passage to the

rear of the cottage.

It had been a mistake to stay on for the sale. She realised , that now.

Mr Frith had warned her that she might find it an upsetting

experience, seeing the place she had thought of as home for the past

six years being literally sold up around her ears. She should have

believed him and moved —not merely out, but away. It was only

sentiment that had caused her to remain, she thought. A longing to

buy just ; something, however small, from among her godmother's

treasures to provide her with a reminder of past happiness. As it was,

the prices that the china, furniture and other antiques were fetching

had only served as a poignant and , disturbing reminder of her own

comparative pennilessness. She must have been mad even to think of

joining in the bidding, knowing that she would be up against dealers

and collectors.

One thing was certain—the Websters would be only too delighted

with the results of the sale. She had seen them sitting together at the

back of the room, exchanging smiles of triumph as the bidding

proceeded. Everything, as far as they were concerned, was going

entirely to plan. It was no good telling herself that they had every

right to do as they

had done. They had made that more than clear already in every

interview she'd had with them. Legally, she had no rights at all, she

knew, and morality didn't enter into it.

She walked despondently into the back kitchen. Like everywhere else

in the cottage, it had been stripped bare of everything saleable, and

the big fitted dresser looked oddly forlorn without its usual

complement of bright willow pattern and copperware.

Christina went over to the sink and ran the cold tap, cupping her hand

beneath it, so that she could drink. She pressed the few remaining

drops of moisture in her palm against her forehead and throbbing

temples.

She still could not fully comprehend the suddenness of the change in

her life and circumstances. She knew, because Mr Frith had endlessly

told her so, that she must think about the future and make some kind

of a plan for herself. But what? It seemed for the past six years she

had been living in some kind of fool's paradise. And for that she had

to thank Aunt Grace, so kind and affectionate in her autocratic way,

and so thoroughly well-meaning towards her orphaned goddaughter,

but when it came to it, so disastrously vague.

After all, as Vivien Webster had patronisingly pointed out to her,

what more could she expect, when she was not even a blood relation?

It was a phrase Mrs Webster was fond of using, often with a delicate

handkerchief pressed to her eyes, or the corner of her mouth, and if

Christina thought it sounded odd coming from someone who had

almost studiously held aloof from Aunt Grace when she was alive,

she kept that strictly to herself.'

Aunt Grace, after all, had been no fool. She had been well aware that

she was regarded as a future meal ticket by her niece and her husband,

yet it had made no difference, apparently. Her brief will had left

everything unconditionally to Vivien Webster, while Christina who

had been het constant companion, run the cottage for her with the

spasmodic help of Mrs Treseder from the village, and done all her

godmother's secretarial work for the various charities with which she

was connected, had not even warranted a mention.

Not that she had ever expected or wanted anything, she reminded

herself. It had always been Aunt Grace who had ' insisted that she had

seen to it that Christina would be well looked after in the event of

anything happening to herself, although she had never specified what

form this care would take. She had said so over and over again,

especially when Christina had tried to gain some measure of

independence by suggesting that she took a training course, , or

acquired some other type of qualification.

'There's no need for that, my dear,' Miss Grantham would remark

bracingly. 'You'll never want, I promise you. I shall see to that, don't

worry.' >

And yet, Christina thought wryly, here she was without

a job, a home or any kind of security—not even allowed so much as a

breathing space in her old home to gather her wits and formulate

some kind of plan for the future. She gave a little painful sigh and

stared out of the window at the small vegetable garden where she and

Aunt Grace had spent so many back-aching hours up to the time of

that last but fatal illness.

Not for the first time she wondered if Aunt Grace had really known

just how ill she had been. Certainly she had robustly rejected all

suggestions that she looked tired, and all urgings to rest more and

conserve her energy in the months preceding her death. In fact she

had seemed to drive herself twice as hard, as if she guessed that she

might not have very much time left, and she had driven Christina hard

too.

Christina gave a slight grimace. She had a whole range of

accomplishments to put in an advertisement—'Capable girl, nineteen,

can cook a little, garden a little, type a little, nurse a little ...' The list

seemed endless. Yet she had to acknowledge that she was a Jill of all

trades and actually mistress of none. Had she anything to offer an

employer more stringent than Aunt Grace had been? This was her

chief worry.

Up to now, of course, her not always expert services had been

accepted, if not always with entire good humour, but she could not

expect that a stranger would be prepared to make the same

allowances for her.

She had been whisked off to live with her godmother when her own

mother, widowed while Christina was still a baby, had herself

succumbed to a massive and totally unexpected heart attack.

Christina had stayed on at the same school, aware for the first time

that the fees were being paid, as they had always been, by Aunt

Grace. When she was sixteen, her godmother had commanded her to

leave school to 'keep her company' and she had perforce to abandon

any idea of further study and obey. Not that it had been such a bad

life, Christina thought, sudden nostalgia tightening her throat. She

had liked the small rather cosy village community of which Aunt

Grace had been so active a member. She had learned to appreciate the

changing seasons with a new and heightened awareness, and had

come to enjoy the pattern of her year and its traditional festivities

without any particular yearning for the discos and parties being

enjoyed by her contemporaries.

Keeping Aunt Grace company had not always been easy. Her

godmother was an imperious woman belonging to a very different

generation. She did not believe in Women's Lib, even in its mildest

form, and it was her openly expressed view that every woman needed

a man to look after her and protect her from what she darkly referred

to as 'folly', though she invariably refused to be more specific.

Her own form of male protection, for she had never married, came in

the substantial shape of Mr Frith, her family solicitor, whose advice

she followed almost religiously on every problem, except apparently

in one instance —that of Christina's future. Mr Frith told Christina

frankly after the funeral and the reading of the will that he had tried

on a number of occasions to persuade Miss Grantham to alter her will

and make some provision for her, but without success.

'She pretended she couldn't hear me,' he told Christina regretfully,

and Christina, who had often been subjected to the same treatment

herself when presenting Aunt Grace with some unpalatable piece of

information, had to sympathise with him.

All Christina could surmise was that Aunt Grace had intended to

make provision for her, but had not been able to decide what form it

should take. And now, of course, it was too late and there was no

point in wondering what this might have been.

It was clear from the very start that Mrs Webster was not prepared to

be magnanimous in any way. Christina was merely an encumbrance

to be shed as soon as possible, and she did not even pretend a polite

interest in the future of the girl who had been her aunt's ward.

Christina was allowed to infer that Mrs Webster thought she was

extremely lucky to have lived in such comfort rent-free for so long,

and that it would do her no harm to stand on her own feet for a

change. Nor did she show any great interest in the cottage or its

contents. She did not want to give up her life in London for a country

existence, and she made it plain she was only interested in converting

her inheritance into hard cash as soon as possible.

Christina had hoped forlornly that the Websters might want to retain

the cottage as a weekend home, and might be prepared to employ her

as a caretaker in their absence, but she was soon disabused of that

notion. And when she quietly asked if Mrs Webster knew of anyone

who might need a. companion to perform the sort of duties that Aunt

Grace had demanded, Mrs Webster had merely shrugged her

shoulders and talked vaguely of agencies and advertisements.

Mr Frith and his wife had been extremely kind, and had promised to

provide her with suitable references when the time came. They had

even invited her to stay with them when it became clear that she

would have to move out of the cottage without delay so that it could

be auctioned with the contents. But Christina had refused their offer.

Perhaps, she had told herself, the Websters had a point and it was

time she did try to gain some independence. After all, she couldn't be

cushioned against life forever. There were other places outside this

little village and outside her total experience, and she would have to

find them.

It was taking the first step that was always the hardest, she decided.

Her own first step had been a room in the village's one hotel, but she

knew this could not be a permanent arrangement. Her small stock of

funds would not permit it, for one thing, and besides, it would soon be

high summer and Mrs Thurston would need the accommodation for

the casual tourists passing through the village on the way to the coast.

As it was, the temporary arrangement suited them both.

Once the auction was over, there would be nothing to hold her here. It

was an odd sensation. She felt as if a gate had closed behind her, and

she stood alone in the centre of an unfamiliar landscape, unknowing

which way to turn.

It was a lonely feeling and she felt tears prick momentarily at the back

of her eyelids. It had occurred to her more than once that Aunt Grace

might have expected her to marry and find sanctuary that way.