The Devil Never Sleeps (17 page)

Read The Devil Never Sleeps Online

Authors: Andrei Codrescu

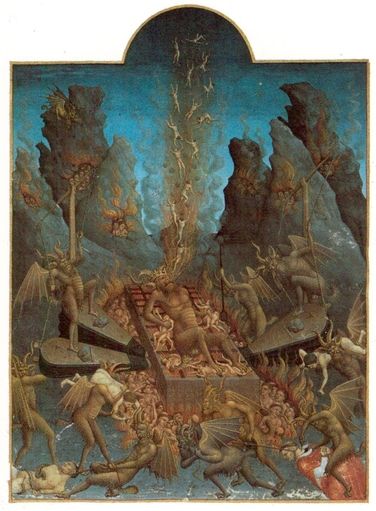

The Duc de Berry, who commissioned the Very Rich Hours to entertain his jaded senses, was particularly fond of the Imagination. The Devil is gratified here by both his earthly senses and his boundless imagination that redeems the tormented after thoroughly enjoying them. The Voyeur extracts Salvation by pulling the Spirit out of the Flesh like a mollusk from a shell.

(Jean Colombe,

Hell, from the Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

. Giraudon/Art Resource, NY)

Hell, from the Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

. Giraudon/Art Resource, NY)

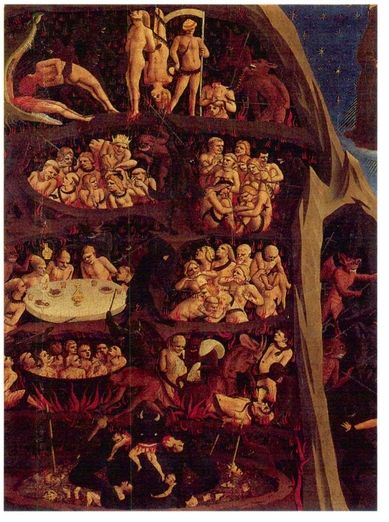

In this special section of Hell, which is the Devil's favorite, the damned are exquisite and tortured exquisitely. One can only imagine, with some frissons, the audition.

(Fra Angelico,

The Last Judgment.

Erich Lessing /Art Resource, NY)

(Fra Angelico,

The Last Judgment.

Erich Lessing /Art Resource, NY)

(below)

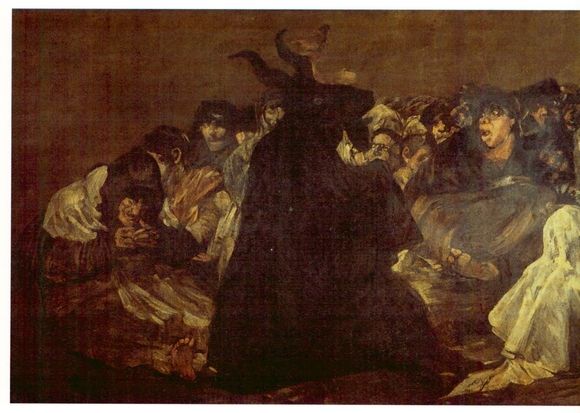

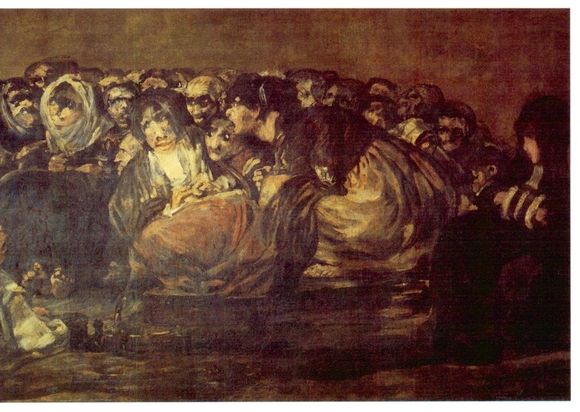

Here is the Devil as Pan and Godfather, old god of nature, dispensing pleasure and power to lustdriven witches, and blessings on his spawn. There is a certain panic behind his eyes, as if he hears the footsteps of the Inquisition in the distance.

(Francisco Goya,

Witches' Sabbath.

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

Witches' Sabbath.

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

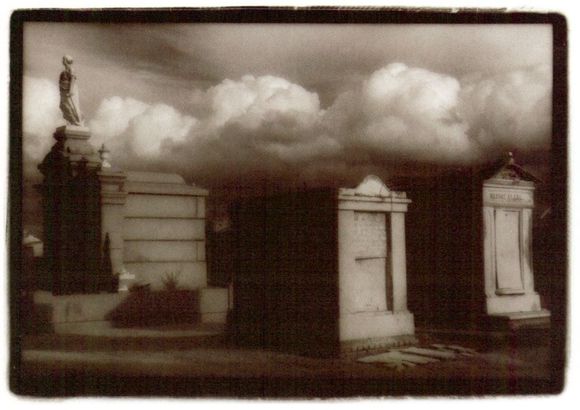

Catholic tombstones are waiting rooms for the Day of Judgment. In their little perennial houses, the dead rehearse their defense for the Almighty, and rest for the day when they will be called to rise and utilize their creaky bodies again.

(Sandra Russell Clark,

Creenwood,

from

Elysium:

A

Gathering of Souls: New Orleans Cemeteries

)

Creenwood,

from

Elysium:

A

Gathering of Souls: New Orleans Cemeteries

)

Â

Â

W

ell, I'm a grandfather. What of it? Grandbébé Marcus is three months old and when I hold him I feel ancient, like a tree. I hold his light, light person, weighing about the same as an average grocery bag, and feel this awesome shoot of energy. His eyes light and widen when he sees me and he smiles, and I am filled with his innocence. Almost everything he sees is for the first time: His gaze finds the things of this world one by one and bathes them in a wide surprised wonder. A bird. A fence. The word

waffle

on the side of the Waffle House. Or perhaps only part of the bird, the red part, and one slat of fence, and the

a

in the waffle. I'm not sure how much of the thing he sees but that much of it lightens up, as if seen for the first time. I can only intuit, like a man in the dark, the vastness of that first gaze.

ell, I'm a grandfather. What of it? Grandbébé Marcus is three months old and when I hold him I feel ancient, like a tree. I hold his light, light person, weighing about the same as an average grocery bag, and feel this awesome shoot of energy. His eyes light and widen when he sees me and he smiles, and I am filled with his innocence. Almost everything he sees is for the first time: His gaze finds the things of this world one by one and bathes them in a wide surprised wonder. A bird. A fence. The word

waffle

on the side of the Waffle House. Or perhaps only part of the bird, the red part, and one slat of fence, and the

a

in the waffle. I'm not sure how much of the thing he sees but that much of it lightens up, as if seen for the first time. I can only intuit, like a man in the dark, the vastness of that first gaze.

His innocence makes me feel simultaneously guilty and awed; guilty because I have forgotten how it was to look on something for the first time; I have even forgotten how to look on something

as if it were

the first time. That's the essence of grandfatherhood then: to have twice forgotten innocence, in both its primary mystery and in the awareness of its necessity. That is what grandbébé Marcus teaches, in his Osh Kosh farmer overalls bulging over diaper, and plump feet like two white yams. My son tells me that one whole month before Marcus laughed while awake, he laughed in his sleep.

What did he laugh at in his dreams, way before he found something to laugh at in our world? Did things present themselves to him in their hilarious wholeness before he actually saw them? I feel him struggling with his body as its needs assert themselves and his laughter changes to crying: hunger, gas, discomfort, growing muscles, tingling nerves, excess of light, heat, cold, all the facts of the body surging through fields of discovery outside himself. Or maybe there is no

outside himself

yet, only a plane of sensations intersecting each other at speeds inconceivable to the slow, diminishing, dim grandfather-tree holding him between two huge limbs. The work of generations, the measure of timeâthey weigh about twenty pounds, have eyes that widen in astonished delight, their name is Marcus, who invents the world as he finds it.

as if it were

the first time. That's the essence of grandfatherhood then: to have twice forgotten innocence, in both its primary mystery and in the awareness of its necessity. That is what grandbébé Marcus teaches, in his Osh Kosh farmer overalls bulging over diaper, and plump feet like two white yams. My son tells me that one whole month before Marcus laughed while awake, he laughed in his sleep.

What did he laugh at in his dreams, way before he found something to laugh at in our world? Did things present themselves to him in their hilarious wholeness before he actually saw them? I feel him struggling with his body as its needs assert themselves and his laughter changes to crying: hunger, gas, discomfort, growing muscles, tingling nerves, excess of light, heat, cold, all the facts of the body surging through fields of discovery outside himself. Or maybe there is no

outside himself

yet, only a plane of sensations intersecting each other at speeds inconceivable to the slow, diminishing, dim grandfather-tree holding him between two huge limbs. The work of generations, the measure of timeâthey weigh about twenty pounds, have eyes that widen in astonished delight, their name is Marcus, who invents the world as he finds it.

Â

Â

M

y friend William Talcott, a poet and a gentleman, complains most bitterly about love in the nineties. He offers himself as an example. He'd fallen madly in love with an unhappily married Japanese woman who reciprocated this love, but then returned to her husband, a boring guy who threatened to drown himself if she didn't rejoin the fold. In response, William produced a beautiful book of verse, entitled

Benita's Book,

which was his lover's name. Like all poets, he credits his beloved with magical powers: “You're also in / my thoughts Benita, your power to heal / imaginary ailments just by smiling.” Of course, it would seem from this that the poet knows that his ailments are imaginary, but you don't know poets. Here is what he says next: “When we touch / that place moves where all lovers goâ/ a pasture by the sea / and you can ride the ponies there.” No longer ailing, he now transports Benita to that imaginary, though crowded, place where lovers and ponies surf. Now, it's easy to find the brokenhearted pathetic, but consider the alternative. “The other day,” William writes to me, “I was on the trolley eavesdropping on two animated young men, discussing the merits of Levi's 505s versus 512s.” Enough said. The callousness in the body proper is clearly but a reflection of the callousness in the body politic.

y friend William Talcott, a poet and a gentleman, complains most bitterly about love in the nineties. He offers himself as an example. He'd fallen madly in love with an unhappily married Japanese woman who reciprocated this love, but then returned to her husband, a boring guy who threatened to drown himself if she didn't rejoin the fold. In response, William produced a beautiful book of verse, entitled

Benita's Book,

which was his lover's name. Like all poets, he credits his beloved with magical powers: “You're also in / my thoughts Benita, your power to heal / imaginary ailments just by smiling.” Of course, it would seem from this that the poet knows that his ailments are imaginary, but you don't know poets. Here is what he says next: “When we touch / that place moves where all lovers goâ/ a pasture by the sea / and you can ride the ponies there.” No longer ailing, he now transports Benita to that imaginary, though crowded, place where lovers and ponies surf. Now, it's easy to find the brokenhearted pathetic, but consider the alternative. “The other day,” William writes to me, “I was on the trolley eavesdropping on two animated young men, discussing the merits of Levi's 505s versus 512s.” Enough said. The callousness in the body proper is clearly but a reflection of the callousness in the body politic.

Another poet, friend of mine, Jim Nisbet, has also produced a wrenching

volumette of the heart entitled

Across the Tasman Sea.

It is the story of a poet abandoned by a woman who chose a professional career over his lyric ministrations. The denouement could have been predicted, since the affair unfolds from letting her drive his car to long-distance phone calls and then, finally, to e-mail. The distance grows as we reach the outer limits of technology, after which the lovers dissolve and the so-called real world reasserts itself. It leaves a poet, Mr. Nisbet in this case, declaring: “Tell me / you're / there / at the end / of this fabulous / bus ride.” He knows she won't, but what's imagination for?

volumette of the heart entitled

Across the Tasman Sea.

It is the story of a poet abandoned by a woman who chose a professional career over his lyric ministrations. The denouement could have been predicted, since the affair unfolds from letting her drive his car to long-distance phone calls and then, finally, to e-mail. The distance grows as we reach the outer limits of technology, after which the lovers dissolve and the so-called real world reasserts itself. It leaves a poet, Mr. Nisbet in this case, declaring: “Tell me / you're / there / at the end / of this fabulous / bus ride.” He knows she won't, but what's imagination for?

Â

Â

T

hese days, I dream of sleep. Sweet narcotic of healing, come to me, I beseech, as I toss restlessly amid the real and imaginary reefs of middleage anxiety. Come to me with all your cool salves, your chasms, your phantoms, and even your hells! I lie awake, reviewing my life, cursing my doctors, disemboweling my enemies, reinterpreting the once sweetly simple, climbing the ladder of the never-ending list of things to do that will never be done. I think of E. M. Cioran, the great philosopher, who suffered also from insomnia: “And while a world interior to our waking solicits us, we envy the indifference, the perfect apoplexy of the mineral,” he said. I have tried melatonin, sleeping pills, valerian extractâall in vain. I have even tried to buy the sleep of others, convinced that those who sleep more than their share are possessed of a magical substance. As I think of the sleepers, the gifted ones, the young, the unconcerned, sleep recedes even further. It isn't fair: I, who am a worshipper of dreams, am locked out of the kingdom of dreams, while others, who have neither the vision nor the skill to fully tend their dreams, get to roll like pigs in the treasures of the moon goddess.

hese days, I dream of sleep. Sweet narcotic of healing, come to me, I beseech, as I toss restlessly amid the real and imaginary reefs of middleage anxiety. Come to me with all your cool salves, your chasms, your phantoms, and even your hells! I lie awake, reviewing my life, cursing my doctors, disemboweling my enemies, reinterpreting the once sweetly simple, climbing the ladder of the never-ending list of things to do that will never be done. I think of E. M. Cioran, the great philosopher, who suffered also from insomnia: “And while a world interior to our waking solicits us, we envy the indifference, the perfect apoplexy of the mineral,” he said. I have tried melatonin, sleeping pills, valerian extractâall in vain. I have even tried to buy the sleep of others, convinced that those who sleep more than their share are possessed of a magical substance. As I think of the sleepers, the gifted ones, the young, the unconcerned, sleep recedes even further. It isn't fair: I, who am a worshipper of dreams, am locked out of the kingdom of dreams, while others, who have neither the vision nor the skill to fully tend their dreams, get to roll like pigs in the treasures of the moon goddess.

It was not always thus. I was a sleepy child once in a dreamy city in a slumbering country at the edge of Europe. Romania was steeped in the sleep of centuries, from which history woke it loudly every three decades or so, in

order to plunge it into a nightmare of death and destruction. My hometown, Sibiu, in Transylvania, was swathed in layered, thick walls, still sporting moss-covered cannonballs from the countless sieges it endured. Inside these walls we slept, my fellow burghers and I, while the half-lidded, somnolent eyes of attics in the steep roofs, watched over our nights. All of our houses, built in the thirteenth century, had owls. They perched on trunks full of German encyclopedias, top hats, discarded armor, rolled-up maps. The Pied Piper of Hamelin, it was said, piped the children of Germany over the mountain here, to Sibiu, where they slept.

order to plunge it into a nightmare of death and destruction. My hometown, Sibiu, in Transylvania, was swathed in layered, thick walls, still sporting moss-covered cannonballs from the countless sieges it endured. Inside these walls we slept, my fellow burghers and I, while the half-lidded, somnolent eyes of attics in the steep roofs, watched over our nights. All of our houses, built in the thirteenth century, had owls. They perched on trunks full of German encyclopedias, top hats, discarded armor, rolled-up maps. The Pied Piper of Hamelin, it was said, piped the children of Germany over the mountain here, to Sibiu, where they slept.

My kingdom of childhood sleep was vast. I slept in hollows on the dark side of the Teutsch cathedral, I slept on the grass in front of the Astra library, and I slept in school with my head on the books, absorbing more of their wisdom than otherwise possible. My favorite book (not a school book) was

A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur's Court

, by Mark Twain. I identified with the Yankee who falls asleep and wakes up in another day and age where his superior knowledge enables him to control the world. I was certain that just over the threshold of my own sleep lay the world meant for me.

A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur's Court

, by Mark Twain. I identified with the Yankee who falls asleep and wakes up in another day and age where his superior knowledge enables him to control the world. I was certain that just over the threshold of my own sleep lay the world meant for me.

Our great romantic poet, Eminescu, spun his verses from moon dust and star gossamer. He dreamed tales of stars who fell in love with mortal girls. Spirits, goblins, ghosts and old sages populated his verse, freshly arrived from the shores of Morphia, goddess of sleep. His poetry fed from the dark soil of fairy tales and songs sung in high mountains beneath sheer walls of granite. The thick forests teemed with creatures eager to enter our dreams: most of them did so directly, but some reached us via Eminescu's poetry. Over in England, Keats, Shelley, Byron, and Coleridge broke open the outer shell of reality's hard nut and let the sweet contents pour out like a purple fog, bringer of dreams, portents, nocturnal voyages. And over in America, Edgar Allan Poe, suspended like a question mark of smoke from the end of his opium pipe, warned the nation of daytime and optimism that a dark dream, an unseen shroud, stretched just below its sunnyness.

The world of sleep is vaster than the world of awakeness. Think of all the nights that stretch from our frightened, monster-haunted human beginnings to the loudness of today when we are doing all we can to banish night. We began in the shelter of the cave, steeped in a nameless dream that had at its center a single flame whose mystery we have not yet fathomed. What was it that woke us from the essential sleep of beasts to the odd knowledge that now compelled us to consider our existence? We awoke from this meditation-dream

only when hunger propelled us to kill, and that was good, because for those few hours we forgot the tormenting flame and happily became beasts again. Eating well caused insomnia, however, so we invented song, art, and poetry, to while away the dark. The nights of the neolithic were long.

only when hunger propelled us to kill, and that was good, because for those few hours we forgot the tormenting flame and happily became beasts again. Eating well caused insomnia, however, so we invented song, art, and poetry, to while away the dark. The nights of the neolithic were long.

Humans have slept fitfully since then. At certain times, history seemed to disappear. A pall of sleep settled over certain ages, obscuring the dailiness of what was, after all, no progress, no development, no awakeness. But when history awoke, it did so with huge explosions, with booms, with cannons, with bombs, with bombast, with men on horses and tanks, an unbearable din of boastful assertion, a rejection of sleep. War woke us up from the eternal contemplation of the dream-flame and put us on the path of Insomnia. Our cities are brightly lit odes to Insomnia, our modern economies are the fruits of sleeplessness. Bowed before blinding small screens, the drones of the working world keep on working past their duty, past what is strictly necessary to bring home the food. The evil goddess of Insomnia rules our world as fiercely as sweet sleep once did it.

Who are the partisans of sleep today? Artists, certainly. Dream is our material, the stuff from which we draw art. One can draw wiggly lines of light from us back to the cave painters at Lascaux and see the dreams we dreamt. Some, like Goya, Bosch, Hoffman, Baudelaire, Lautreamont, Rimbaud, Freud, André Breton, declared the poetry of the dream openly. Others simply fed at the dark fountain and felt themselves expand. Some mystical poets have denied the waking world any reality at all, maintaining that we are all a dream in the mind of God, dreaming of that which dreams us. That “that” was once a butterfly for Lao Tsu. Of course, most people of the world have known, just like Lope de Vega, that “la vida es sueño.” Even our superficial pop singers give it to us without respite, “life is but a dream, ah, ah!”

Some philosophers and scientists have to be included among artists. Insights bombarded them in sleep, apples hit them with force and revelation, atoms arranged themselves behind their closed eyelids. All thinkers speak with wonder of the state just before sleep, the antechamber of sleep, the residence of Sister Hypnagogia. It is there that most great revelations are encountered. But only those with the fortitude to rise and commit their visions to paper can wrench these jewels from the night.

Pregnant women cherish their sleep, whose calming waters they float in

just like the child floats inside them. The amniotic waters of sleep, our first, are also the sites of our first dreams. Today's doctors are as keen on sleep as the early medicine men: They don't know how or why but literal sleep heals it. Whether we are all asleep or not, the vastness of the unconscious is greater than the shards of what we know.

just like the child floats inside them. The amniotic waters of sleep, our first, are also the sites of our first dreams. Today's doctors are as keen on sleep as the early medicine men: They don't know how or why but literal sleep heals it. Whether we are all asleep or not, the vastness of the unconscious is greater than the shards of what we know.

Other books

No Place for a Lady by Maggie Brendan

Clover's Child by Amanda Prowse

The Glass Prison by Monte Cook

On the Ropes (Fighting For Love Book 2) by Glass, Evelyn

The Widow's Guide to Sex and Dating by Carole Radziwill

In the Danger Zone by Stefan Gates

The Fires Beneath the Sea ebook by Lydia Millet

Crazy in Paradise by Brown, Deborah

Way Station by Clifford D. Simak

The Jaguar by A.T. Grant