The Dirt (45 page)

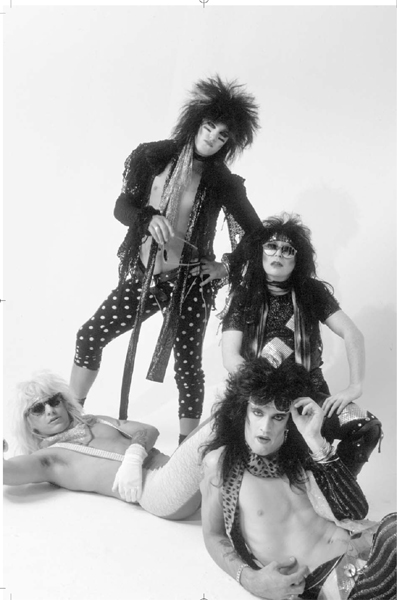

Authors: Tommy Lee

We shall also see in the following pages how Mötley Crüe returned to the conveyer belt, how they caught cogs again, and how they were crushed and thrown around by the machinery as never before, leading them to prison cells, hospital beds, celebrity marriages, and worse.

References

Dannen, Frederic,

Hit Men

. Vintage Books, 1991.

Kravilovsky, William M., and Sidney Shemel,

This Business of Music

.

Billboard Books, 1995.

Sanjek, Russel,

Pennies from Heaven: The American Popular Music Business in the Twentieth Century

. Da Capo, 1996.

Whitburn, Joel,

Top Pop Albums: 1955–2000

. Record Research, 2000. Guns N’ Roses,

The Spaghetti Incident?

Geffen Records, 1992.

Coming Soon from the Same Authors

“Divorce and Downloading Theory: An Examination of the Wireless Communication System through Which All Females Are Linked, Allowing Constant Telepathic Surveillance of the Activities of Their Mates.”

R

onnie James Dio changed my life—twice. The first time, I had graduated from Cortland State in New York in 1967 and joined his band, Ronnie Dio and the Prophets. Driving to Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in our van, we were in a head-on collision and I almost lost my leg. I was in traction in Hartford when I received my physical notice for Vietnam. I looked at the doctor and he told me not to worry: I wouldn’t have to serve in the war.

Years later, in the summer of ’82, I was in Manhattan running tours for Contemporary Communications Corp. when I received a call from Tom Zutaut. He said he had signed this group Mötley Crüe to Elektra and wanted to put them on the Aerosmith tour. He hinted that there might be management possibilities. However, I had just put an old agency client of mine, Pat Travers, on the Aerosmith bill, so Zutaut was out of luck. Besides, David Krebs, the head of our company, didn’t think it made any sense for a New York–based company to take on an L.A. client.

I had heard of the Mötley Crüe once before Zutaut, when Hernando Courtright at A&M Records showed me the Leathür Records release of

Too Fast for Love

and said he was high on it and wanted to sign the band. The cover was a cheesed-up picture that I later found out had been taken by a wedding photographer who had superimposed hair on the guys. It looked pretty comical, and I didn’t think much about it.

It was then that Ronnie James Dio came back into my life. He told me about a band with a flashy drummer that he liked. At the same time, Pat Travers’s manager, Doc McGhee, wanted me to join his company. I took him up on his offer on blind faith because I was going nowhere in my job. The first thing that Doc and I did together was head out to Los Angeles to see this band that Dio was talking about. It was Mötley Crüe again, and they knocked us out. They weren’t nearly as cheesy as my first impression. The singer had a unique voice and raw energy, the music had a great pop twist to it, and the show was unbelievable. This was a hit act: you could take them anywhere in the world and put them in front of people, and they’d kill. As soon as I saw them, I knew that all the work I’d done in the business beforehand was like going to college so I’d know what to do with this band.

From the beginning of the band’s tour with Kiss, a work ethic materialized that I never expected. The guys turned into animals live. With Vince running all over the stage and Nikki exploding with bad-boy attitude, they put on such a knockout show that they were upstaging Kiss. With the exception of only two or three shows, the band was so consistently good live through

Shout, Girls, Theatre

, and the first two-thirds of

Feelgood

that the hair on the back of your neck would stand up at some point or another during every concert.

But managing this band offstage was never easy. These are four damaged individuals. Vince is a California surfer-rock guy, the peacock of peacocks, who never really had to work for his fame. I think the ill will toward him began after the car crash with Razzle, because the group would be playing charity shows for him and he’d go off drinking, fucking around, and putting the band’s future at risk. To be fair, though, no one really understood the disease of alcoholism at the time.

Mick Mars was the exact opposite of Vince: a guy who had wiped shit off his head for his whole life and was thankful just to have a moment in the sun, even if it ended the next day. Nikki was basically a nerd, except when he had Jack Daniel’s in him, which was just about every night. And Tommy was like a little kid, running around looking for mother and father figures. He could be the sweetest, most big-hearted kid in the world or the most spoiled, temperamental brat. But it was always either Vince’s behavior or Nikki’s drug addiction that jeopardized the band.

That changed, though, when the band sobered up for

Feelgood

, which was a tremendous triumph. The combination of the new sobriety, the stress from their marriages, and the attainment of a level of success beyond what they had ever imagined began to work a change in the band. Fear, exhaustion, and mood swings set in, and Tommy and Vince started falling off the wagon. Nikki, who had married a girl he had hardly even seen because he was so busy, became really distasteful to deal with. Everyone was blowing smoke up his ass, and he was starting to believe them. At the height of his powers, he was a marketing genius, but now he’d call the office pissed off because his carpenter thought

Feelgood

should have sold 7 million copies instead of just 4.5 million. And there was nothing we could do or say to calm him.

I wanted the band to have a long time to work on their next album. I knew it would be very difficult to write a follow-up to

Dr. Feelgood

, and there was a chance that by waiting to record they could get a new contract with Elektra that would earn them twenty-five million dollars. At the same time, they needed downtime to deal with their new children: within months of each other, Vince and Sharise had their first daughter, Skylar, and Nikki and Brandi had their first son, Gunner. And Tommy, left out, really started wanting to have a child of his own with Heather.

As the new Elektra deal was being negotiated, things with the band kept going more haywire. Vince was getting back into drink again. He’d come to rehearsals for the new album a mess, and then leave early because he had to boff some porn star on his way home. By spring 1991, I had to call him and tell him that he wasn’t welcome at rehearsals until he got his act together. So Vince grabbed some porn star, flew to Hawaii without telling us, and maxed out all his charge cards until he had to return home, where Sharise was impatiently waiting to kill him. He quickly pacified her—he was so good that if you walked into your bedroom and he was banging your wife, within five minutes he would have talked you out of believing what you had just seen. Then he took a plane to Tucson and checked himself into rehab.

We all flew down there and met with Vince, encouraging him to make the band a priority and explaining that we would be there to support him as long as he tried to be there for us. Vince swore he wasn’t just along for the ride and promised to make an effort.

Afterward, we played on the Monsters of Rock tour in Europe with AC/DC, Metallica, and Queensryche, and that was the first time that the shows didn’t make the hair on the back of my neck stand up. Though they had so many hits they should have wiped almost every other band off the stage, something was missing: they didn’t feel real anymore, and the prerecorded tapes they used to replace their backup singers sounded phony to the crowd.

Back home, when

Decade of Decadence

came out, Nikki started spending half his nights at hotels because he was fighting with his wife. Vince, meanwhile, was off on a racing jag. It always seemed like a great little hobby for him until some jerk-off in Long Beach convinced him to race on an Indy Lights team, where I was sure some driver was going to see this rock-and-roll asshole on the track and try to kill him. He started spending his weekends at race-car conferences, where we’d hear reports that he’d been up all night drinking.

I put them back in the studio in December 1991, on a two-week-on, two-week-off schedule. But every time I went down to visit, Vince wasn’t there. He’d have left the studio after a few hours, claiming he was too tired to sing.

Finally, in February, the band started to get pissed.

O

n Monday, the floods began. The waters swept over the Ventura freeway, flooded the Sepulveda Basin, killed six people, and left hundreds more hanging on to telephone poles and antennas for their lives. On the radio, Governor Pete Wilson declared a state of emergency and said that we were in the midst of the worst storm of the century. That didn’t matter, though, to Tommy and me. We drove for two hours to get to rehearsal in Burbank from Westlake Village while Mick, who was up in the mountains somewhere, had an even more grueling ride. We met in the studio lounge and waited for Vince. On the news, we watched people swimming out of their cars on Burbank Boulevard. One hour passed. Two hours passed. Three hours passed. Four hours passed. We called Vince every half hour, but each time there was a busy signal.