The Discomfort Zone (12 page)

Read The Discomfort Zone Online

Authors: Jonathan Franzen

Â

MANLEY'S PARENTS WERE

permissive, and Kortenhof's house was big enough to exit and enter inconspicuously, but most of us had trouble getting away from our parents after midnight. One Sunday morning, after two hours of sleep, I came down to breakfast and found my parents ominously untalkative. My father was at the stove frying our weekly pre-church eggs. My mother was frowning with what I now realize was probably more fear than disapproval. There was fear in her voice as well. “Dad says he heard you coming in the front door this morning after it was light,” she said. “It must have been six o'clock. Were you out?”

Caught! I'd been Caught!

“Yeah,” I said. “Yeah, I was over at the park with Ben and Chris.”

“You said you were going to bed early. Your light was off.”

“Yeah,” I said, looking at the floor. “But I couldn't sleep, and they'd said they'd be over at the park, you know, if I couldn't sleep.”

“What on earth were you doing out there so long?”

“Irene,” my father warned, from the stove. “Don't ask the question if you can't stand to hear the answer.”

“Just talking,” I said.

The sensation of being Caught: it was like the buzz I once got from some cans of Reddi-wip whose gas propellent I shared with Manley and Davisâa ballooning, dizzying sensation of being all surface, my inner self suddenly so flagrant and gigantic that it seemed to force the air from my lungs and the blood from my head.

I associate this sensation with the rushing heave of a car

engine, the low whoosh of my mother's Buick as it surged with alarming, incredible speed up our driveway and into our garage. It was in the nature of this whoosh that I always heard it earlier than I wanted or expected to. I was Caught privately enjoying myself, usually in the living room, listening to music, and I had to scramble.

Our stereo was housed in a mahogany-stained console of the kind sold nowadays in thrift stores. Its brand name was Aeolian, and its speakers were hidden behind doors that my mother insisted on keeping closed when she played the local all-Muzak station, KCFM, for her dinner guests; orchestral arrangements of “Penny Lane” and “Cherish” fought through cabinetry in a muffled whisper, the ornate pendent door handles buzzing with voices during KCFM's half-hourly commercial announcements. When I was alone in the house, I opened the doors and played my own records, mostly hand-me-downs from my brothers. My two favorite bands in those pre-punk years were the Grateful Dead and the Moody Blues. (My enthusiasm for the latter survived until I read, in a

Rolling Stone

review, that their music was suited to “the kind of person who whispers âI love you' to a one-night stand.”) One afternoon, I was kneeling at the Aeolian altar and playing an especially syrupy Moodies effort at such soul-stirring volume that I failed to hear my mother's automotive whoosh. She burst into the house crying, “Turn that off! That awful rock music! I can't stand it! Turn it off!” Her complaint was unjust; the song, which had no rock beat whatsoever, offered KCFMish sentiments like

Isn't life strange / A turn of the page /â¦it makes me want to cry

. But I nevertheless felt hugely Caught.

The car I preferred hearing was my father's car, the Cougar he commuted to work in, because it never showed up unexpectedly. My father understood privacy, and he was eager to accept the straight-A self that I presented to him. He was my rational and enlightened ally, the powerful engineer who helped me man the dikes against the ever-invading sea of my mother. And yet, by temperament, he was no less hostile to my adolescence than she was.

My father was plagued by the suspicion that adolescents were

getting away with something

: that their pleasures were insufficiently trammeled by conscience and responsibility. My brothers had borne the brunt of his resentment, but even with me it would sometimes boil over in pronouncements on my character. He said, “You have demonstrated a taste for expensive things, but not for the work it takes to earn them.” He said, “Friends are fine, but all evening every evening is too much.” He had a double-edged phrase that he couldn't stop repeating whenever he came home from work and found me reading a novel or playing with my friends: “One continuous round of pleasure!”

When I was fifteen, my Fellowship friend Hoener and I struck up a poetic correspondence. Hoener lived in a different school district, and one Sunday in the summer she came home with us after church and spent the afternoon with me. We walked over to my old elementary school and played in the dirt: made little dirt roads, bark bridges, and twig cottages on the ground beneath a tree. Hoener's friends at her school were doing the ordinary cool thingsâdrinking, experimenting with sex and drugsâthat I wasn't. I was scared of Hoener's beauty and her savoir faire and was relieved to discover that she and I shared romantic views of childhood. We were old enough not to be ashamed of playing like little kids, young enough to still become engrossed in it. By the end of our afternoon, I was close to whispering “I love you.” I thought it was maybe four o'clock, but when we got back to my house we found Hoener's father waiting in his car. It was six-fifteen and he'd been waiting for an hour. “Oops,” Hoener said.

Inside the house, my dinner was cold on the table. My parents (this was unprecedented) had eaten without me. My mother flickered into sight and said, “Your father has something to say to you before you sit down.”

I went to the den, where he had his briefcase open on his lap. Without looking up, he announced, “You are not to see Fawn again.”

“What?”

“You and she were gone for five hours. Her father wanted to know where you were. I had to tell him I had no idea.”

“We were just over at Clark School.”

“You will not see Fawn again.”

“Why not?”

“Calpurnia is above suspicion,” he said. “You are not.”

Calpurnia? Suspicion?

Later that evening, after my father had cooled off, he came to my room and told me that I could see Hoener again if I wanted to. But I'd already taken his disapproval to heart. I started sending Hoener asinine and hurtful letters, and I started lying to my father as well as to my mother. Their troubles with my brother in 1970 were the kind of conflict I was bent on avoiding, and Tom's big mistake, it seemed to me, had been his failure to keep up appearances.

More and more, I maintained two separate versions of myself, the official fifty-year-old boy and the unofficial adolescent. There came a time when my mother asked me why all my undershirts were developing holes at navel level. The official version of me had no answer; the unofficial adolescent did. In 1974, crewneck white undershirts were fashion suicide, but my mother came from a world in which colored T-shirts were evidently on a moral par with water beds and roach clips, and she refused to let me wear them. Every morning, therefore, after I left the house, I pulled down my undershirt until it didn't show at the collar, and I safety-pinned it to my underpants. (Sometimes the pins opened and stuck me in the belly, but the alternativeâwearing no T-shirt at allâwould have made me feel too naked.) When I could get away with it, I also went to the boys' bathroom and changed out of certain grievously bad shirts. My mother, in her thrift, favored inexpensive tab-collared knits, usually of polyester, which advertised me equally as an obedient little boy and a middle-aged golfer, and which chafed my neck as if to keep me ever mindful of the shame of wearing them.

For three years, all through junior high, my social death was grossly overdetermined. I had a large vocabulary, a giddily squeaking voice, horn-rimmed glasses, poor arm

strength, too-obvious approval from my teachers, irresistible urges to shout unfunny puns, a near-eidetic acquaintance with J.R.R. Tolkien, a big chemistry lab in my basement, a penchant for intimately insulting any unfamiliar girl unwise enough to speak to me, and so on. But the real cause of death, as I saw it, was my mother's refusal to let me wear jeans to school. Even my old friend Manley, who played drums and could do twenty-three pull-ups and was elected class president in ninth grade, could not afford to see me socially.

Help finally arrived in tenth grade, when I discovered Levi's straight-legged corduroys and, through the lucky chance of my Congregational affiliation, found myself at the center of the Fellowship clique at the high school. Almost overnight, I went from dreading lunch hour to happily eating at one of the crowded Fellowship tables, presided over by Peppel, Kortenhof, and Schroer. Even Manley, who was now playing drums in a band called Blue Thyme, had started coming to Fellowship meetings. One Saturday in the fall of our junior year, he called me up and asked if I wanted to go to the mall with him. I'd been planning to hang out with my science buddy Weidman, but I ditched him in a heartbeat and we never hung out again.

Â

At lunch on Monday, Kortenhof gleefully reported that our padlock was still on the flagpole and that no flag had been raised. (It was 1976, and the high school was lax in its patriotic duties.) The obvious next step, Kortenhof said, was to form a proper group and demand official recognition. So we wrote a noteâ

Dear Sir,

We have kidnapped your flagpole. Further details later.

âmade a quick decision to sign it “U.N.C.L.E.” (after the sixties TV show), and delivered it to the mail slot of the high-school principal, Mr. Knight.

Mr. Knight was a red-haired, red-bearded, Nordic-

looking giant. He had a sideways, shambling way of walking, with frequent pauses to hitch up his pants, and he stood with the stooped posture of a man who spent his days listening to smaller people. We knew his voice from his all-school intercom announcements. His first wordsâ“Teachers, excuse the interruption”âoften sounded strained, as if he'd been nervously hesitating at his microphone, but after that his cadences were gentle and offhanded.

What the six of us wanted, more than anything else, was to be recognized by Mr. Knight as kindred spirits, as players outside the ordinary sphere of student misbehavior and administrative force. And for a week our frustration steadily mounted, because Mr. Knight remained aloof from us, as impervious as the flagpole (which, in our correspondence, we liked to represent as personally his).

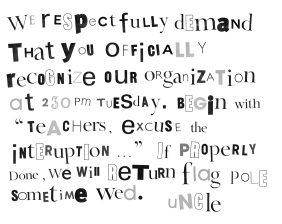

After school on Monday, we cut and pasted words and letters from magazines:

The phrase “Teachers, excuse the interruption” was Manley's idea, a poke at Mr. Knight. But Manley was also worried, as was I, that the administration would crack down hard on our little group if we got a reputation for vandalism, and so we returned to school that night with a can of aluminum paint and repaired the damage we'd done to the flagpole in

hammering the old lock off. In the morning, we delivered the ransom note, and two-thirty found the six of us, in our respective classrooms, unreasonably hoping that Mr. Knight would make an announcement.

Our third note was typed on a sheet of notepaper headed with a giant avocado-green

HELLO

:

Being as we are a brotherhood of kindly fellows, we are giving you one last chance. And observing that you have not complied with our earlier request, we are hereby reiterating it. To wit: your official recognition of our organization over the public address system at 2:59, Wednesday, March 17. If you comply, your flagpole will be returned by Thursday morning.

U.N.C.L.E.

We also made an U.N.C.L.E. flag out of a pillowcase and black electrician's tape and ran it up the flagpole under cover of night. But Mr. Knight's office didn't even notice the flag until Kortenhof casually pointed it out to a teacherâtwo maintenance workers were then sent outside to cut our lock with a hacksaw and lower the pirate flagâand he ignored the note. He ignored a fourth note, which offered him two dollars in compensation for the broken school padlock. He ignored a fifth note, in which we reiterated our offer and dispelled any notion that our flag had been raised in celebration of St. Patrick's Day.

By the end of the week, the only interest we'd succeeded in attracting was that of other students. There had been too much huddling and conspiring in hallways, too much blabbing on Kortenhof's part. We added a seventh member simply to buy his silence. A couple of girls from Fellowship grilled me closely: Flagpole? Uncle? Can we join?

As the whispering grew louder, and as Kortenhof developed a new plan for a much more ambitious and outstanding prank, we decided to rename ourselves. Manley, who had a half-insolent, half-genuine fondness for really stupid humor, proposed the name DIOTI. He wrote it down and showed it to me.

“An anagram for âidiot'?”

Manley giggled and shook his head. “It's also

tio

, which is âuncle' in Spanish, and âdi,' which means âtwo.' U.N.C.L.E. Two. Get it?”

“Di-tio.”

“Except it's scrambled. DIOTI sounds better.”

“God, that is stupid.”