The Doctor Digs a Grave (3 page)

Read The Doctor Digs a Grave Online

Authors: Robin Hathaway

SAME EVENING, 9:30 P.M.

“

D

id you say this was an Indian burial ground?” Rafferty was slouched against the bank wall next to Fenimore, waiting for his homicide squad to arrive. He had put the order through on his radio a few minutes earlier.

D

id you say this was an Indian burial ground?” Rafferty was slouched against the bank wall next to Fenimore, waiting for his homicide squad to arrive. He had put the order through on his radio a few minutes earlier.

“That's right,” Fenimore said.

The policeman had offered to call a squad car to take Fenimore to the hospital, but Fenimore had refused. After suffering this much, he was damned if he was going to miss all the fun.

“I feel their spirits watching me right now,” Rafferty said.

“Whose?”

“The Indians'.” He stirred anxiously, glancing around. “I wish I had a pint.”

“How did somebody who's afraid of ghosts get to be a top cop in Philadelphia?”

“Ghosts aren't Philadelphia's problem.”

“Shall I sing?” Fenimore was beginning to feel better.

“Please don't.”

That was all the encouragement he needed. He began to croon, “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling.”

“Can it. Why did you have to go and dig up a corpse two days before Halloween? Tomorrow's Mischief Night. We have to work extra shifts, and the department's overworked as it is.”

“That's why you had time to watch the Phillies?”

“Can it.”

“You're getting repetitive.”

“Canâ” Rafferty got to his feet and began pacing the perimeter of the small space, careful to avoid the hole and its occupant. The limited exercise seemed to give him no relief He disappeared down the alley to look for his reinforcements.

As soon as he left, Fenimore's head began to throb again. After what seemed a long time, he heard heavy footsteps in the alley, and Rafferty reappeared with his personal army in tow: two police officers, a detective, the medical examiner, and a photographer. From then on business was brisk. Fenimore, feeling uncharacteristically useless, remained against the bank wall.

“Hey, Fenimore, look at this!”

Fenimore leaped to his feet and nearly fainted. The pain surged through his head, almost blinding him. A combination of curiosity and sheer willpower carried him the few steps to look into what had now become a large hole.

There was nothing unusual about the woman's appearance. Eyes closed, tawny skin, black hair. She was simply dressed in a T-shirt, jeans, and sandals. And there were no visible marks on her face, arms, hands, or feet. It was obvious she had been buried recently, within the past two or three hours. There was no evidence of decomposition or decay, and the medical examiner had assured them that rigor mortis was just beginning to set in. It was her posture that was unusual. Instead of lying flat, in the accepted burial position, her body was flexed, knees tucked under her chin, arms crossed over her chest.

Fenimore whistled. “And look how she's facing.”

Rafferty stared at him.

Fenimore returned his stare. “It's traditional, among the Lenni-Lenape Indians, to bury their dead in a flexed position, turned toward the east.

SUNDAY AFTERNOON, OCTOBER 30

F

enimore lay on the sofa, pressing an ice pack to the side of his head. The TV was on, but he wasn't watching it. He never watched it, unless he was too sick to read or in too much pain to sleep and needed an excuse to do absolutely nothing without appearing to be brooding.

enimore lay on the sofa, pressing an ice pack to the side of his head. The TV was on, but he wasn't watching it. He never watched it, unless he was too sick to read or in too much pain to sleep and needed an excuse to do absolutely nothing without appearing to be brooding.

Sal lay curled at his side, her head turned pointedly away from the screen. She shared his opinion of TV. Every now and then an image on the screen would catch Fenimore's attentionâan obnoxious news anchor, an idiotic commercial, or a pretty girl, oops, attractive female person. The first might extract an oath; the second, a snort; the third, a grin. That was the extent of his reaction to the media. Today he felt too terrible to react at all.

Fenimore lay perfectly still in order not to jar his head while he stroked Sal. Most of the time he kept his mind a perfect blank, but every now and then the events of the previous night intruded. Questions rose up. Who hit him? Why? He would stop stroking Sal to ponder these questions until she registered her annoyance with an abrupt

“Meow!”

Then he would resume stroking.

“Meow!”

Then he would resume stroking.

Was the person who had assaulted him the same person who had buried the body? Or an accomplice? How did this person know he had discovered the body? He had been so careful not to let on to the boy. Had the person been lurking nearby when he and Horatio had been engaged in their funeral ritesâan uncomfortable thoughtâand bashed Fenimore on the off chance that he had discovered the body?

“Meow!”

Stroke, stroke, stroke.

Had the person meant to do more than injure him and been interrupted? Sal reacted to his too-vigorous stroking by leaping off the sofa.

The phone. He reached for it.

“Andrew?”

Jennifer.

“Dan just called to say you needed cheering up. Is something wrong?”

Blast him. “Not a thing. Can't imagine what ⦠he ran into me at the wrong time ⦠right after a department meeting. You know how they always funk me up. What are you doing today?”

“Oh, Dad has me inventorying some books that came in Friday from an estate on the Main Line.”

“Can they read out there?”

“Snob. Actually, these books belonged to a judge, and they're quite dog-eared.”

“Not the usual mint condition, chosen because the binding matched the drapes?”

“No, seriously, he even has an impressive collection of mysteries. Mostly trial stuff, but there are a couple of early Chandlers.”

“Hey, could you save me those? I'd like to take a look at them.”

“I have a better idea. I'll bring them over.”

“Uh, I'm sort of in the middle of something. Billing time ⦠end of the month.”

“I thought Mrs. Doyle took care of all that.”

“Usually, but she was on vacation this month. Things pile up.”

“I see.” She sounded hurt. “I'll let you go then.”

“Maybe you could invite me for dinner some night, and your dad could fill me in on the Lenni-Lenape Indians.”

“Why?”

“They're a subject of interest to me right now.”

“We have a shelf of books about them.”

“Great. I'll be over soon.”

“Shall I serve venison and wild rice garnished withâ”

“Poison ivy?”

“That depends.”

“On what?”

“Lots of things.” On this enigmatic note, she hung up.

Fenimore examined his motives. Why had he put Jennifer off? Had he really not wanted her to come? Or did he fear being comforted? Did he secretly yearn to be fed bouillon and read to and generally have his hand held? In short, was he getting soft? If that was the case, he was in the wrong business. Instead of an income supplement, his little sideline might quickly turn into a health hazard. Not that brawn was a weapon he often relied on in his investigations. He didn't have any. His method was to match wits with his adversaries. But even matching wits required a certain amount of independence and self-reliance. That's why he had put Jennifer off.

MONDAY, OCTOBER 31

I

t was Monday morning. Halloween morning to be exact. The city had made it through another Mischief Night relatively unscathed. So had Fenimore. He had recovered from his head wound enough to sit in his office and read a coroner's report.

t was Monday morning. Halloween morning to be exact. The city had made it through another Mischief Night relatively unscathed. So had Fenimore. He had recovered from his head wound enough to sit in his office and read a coroner's report.

Mrs. Doyle, his nurse-secretary for more than fifteen years, and his father's before him, was at her typewriter. (Fenimore had offered to buy her a word processor, but she had emphatically refused. None of those bits and bites and chips for her, thank you. She'd stick to her faithful old Smith Corona.) The fiery hair of her youth had mellowed to a dusty rose (redheads never turn gray), and her curves had acquired some padding. To the patients she resembled a comfortable old sofa that welcomed them into its depths, offering comfort and solace. But underneath all that mellowness and padding lay a keen mind and a sharp tongue, which, like a taut spring, could break through the upholstery at a moment's notice.

The spring had sprung that morning when she walked into the office and saw Fenimore's face: black and blue from eyebrow

to chin on one side and a nasty scab over the left ear. “What hit you?” she demanded belligerently. Her concern for the doctor always took the form of anger.

to chin on one side and a nasty scab over the left ear. “What hit you?” she demanded belligerently. Her concern for the doctor always took the form of anger.

Fenimore, in response to her concern, always acted like a truculent boy who didn't want to explain things to his mother. “Nothing much. Just a small shovel.”

“A large bulldozer, more likely.” She punctuated her observation with a loud snort. “Have you seen a doctor?” A rhetorical question; she already knew the answer.

Fenimore didn't disappoint her. “I

am

a doctor,” he said and returned to his report.

am

a doctor,” he said and returned to his report.

She drew a sharp breath. Every now and then the doctor fell into a pose so like his late father's that it gave her a turn. They were similar in appearanceâslight and wiry with a tendency toward balding. And they both suffered from weak eyesight. Father and son each had the habit of leaning on his right arm while reading and making a visor of his right hand to shield his eyes against the lamp's glare. Today one was swollen shut.

Fenimore scanned the first page of the report:

Name: Unknown

Address: Unknown

Phone number: Unknown

Social Security #: Unknown

Sex: Female

Age: Between 23 and 25

Hair: Dark brown

Eyes: Dark brown

Weight: 118 lbs.

Race: Native American

Marks of identification: Scar on chest; evidence of heart operation in childhood to correct tetralogy of Fallot

“Tetralogy of Fallot?”

Mrs. Doyle looked up from her typing. “Doctor?”

He was reading again.

Stomach contents: Residue of recent meal. Shreds of beef, mushrooms, onions, peppers, lettuce, tomatoes, bread

Cause of death: Heart failure

The phone rang at his elbow.

“Ready to man the battlements for Liska?” It was Larry Freeman, his resident.

Fenimore outlined the plan he had conceived to rescue Mr. Liska from one of the more aggressive cardiology teams at the hospital. He gave the young doctor detailed instructions. When he hung up, he was satisfied that another blow had been struck for the welfare of the patient. He had barely replaced the receiver when the phone rang again.

“Help.”

Rafferty. “The pathologist just left. She was here for over an hour jawing about blue babies. I didn't understand a word. Can you get over here and translate?”

“I'll be right over.” Fenimore fumbled in the side drawer of his desk. He found what he wanted and stuffed it in his pocket. “I'm going out, Doyle. If there's an emergency, get me at Rafferty's office.” He disappeared down the long narrow hall.

“Doyle”? He called her that only when they were about to embark on a case. That, combined with the state of his face, assured her that he was up to something. Mrs. Doyle returned to pounding her typewriter. If there had been a law against typewriter abuse, she would have been serving time long ago. But she wanted to finish her office work in order to be free to help with this new caseâand more important, to get her hands on the monster who had banged up the doctor's face.

Â

Â

When Fenimore came in, Rafferty examined him critically. “Typical doctor, won't see a doctor.”

“Don't you start. I've just escaped Doyle. And what's the idea of squealing to Jennifer.”

“I just thought you needed a little TLC.”

“Well, next time you feel like playing cupid, don't.”

“Whew. What side of the bed did you get up on?”

“I slept on the couch. So you want to know about blue babies?” Fenimore swiftly changed the subject.

“Yeah. And keep it simple. That pathologist talked a lot of gobbledygook.” He rubbed his temples. “What's that?” He was quick to notice the bulge in Fenimore's jacket pocket.

Fenimore took out an object about the size of a softball and set it on Rafferty's desk. It was a small plastic model of a heart. “Take it apart.”

Rafferty, after a startled look, began to dismantle it, laying the pieces in a neat row in front of him. When he had it all apart, he looked up like a good child expecting a pat on the head.

“Now for the hard part,” Fenimore said. “Put it back together.”

After a few false starts, Rafferty succeeded.

“Good. Now you're ready.” Fenimore launched into a definition of tetralogy of Fallot.

“Tetralogy of Fallot is a heart condition found in some newborns that causes cyanosisâthe so-called blue babies. The cyanosis is caused by some of the blood not getting enough oxygen in the lungs. Blood without enough oxygen is blue.” Fenimore pointed to the veins in his left hand. “After the blood gets oxygen in the lungs, it becomes red. In tetralogy of Fallot there are four, or tetra”âhe held up four fingersâ“factors that prevent blood from getting to the lungs and receiving oxygen. Oh, and Fallot is the French fellow who discovered it all. Now there's a

surgical operation that can correct this condition, and with the help of medicines, the kid can live a relatively normal life.”

surgical operation that can correct this condition, and with the help of medicines, the kid can live a relatively normal life.”

“How come you didn't just say, âThis condition keeps blood from getting to the lungs to pick up oxygen'?”

Fenimore sighed. “And have you think I spent all those years in medical school drinking and carousing?” That was how Fenimore had met Rafferty. One balmy spring evening he and some other medical students had been involved in a harmless, drunken prank (hurling water balloons at unsuspecting passengers seated next to open windows in trolley cars). Rafferty, barely more than a rookie himself, had threatened him and the others with arrest on charges of assault and battery. The lean, dark policeman (he could have been a stand-in for a young Gregory Peck) had even had the temerity to accuse Fenimore of being the instigator. But the silver-tongued medical student had managed to convince him that no harm had been done. Not only did Rafferty let them go, he agreed to meet Fenimore later, when he was off duty, for a few beers at The Raven, a shabby dive with pretensions to having once served the famous author, Edgar Allan Poe. It had been their favorite haunt ever since.

“Now let's get down to the important business.” Rafferty tipped back in his chair, clasping his hands behind his head. He still looked like a movie star, albeit an aging one. His black hair had some gray in it, and there was the slightest hint of a bulge at his waistâeven though, Fenimore knew, he worked out regularlyâbut his eyes were the same deep blue, and his gaze was, if anything, sharper and more penetrating. “Could the condition revealed in the coroner's report cause sudden death many years after the operation?”

Fenimore pondered. “It's a definite possibility. You see,” he pointed to the septal wall in the model, “this area where the surgical repair took place is also where the electrical conductor of the heart is located. When this conductor is disturbed by

surgery, it may not conduct beats properly. And more important, years after the surgery it might cause ventricular arrhythmias that could result in ventricular fibrillation and syncopeâ”

surgery, it may not conduct beats properly. And more important, years after the surgery it might cause ventricular arrhythmias that could result in ventricular fibrillation and syncopeâ”

“Whoa!” Rafferty held up his hand. “You're beginning to sound like that pathologist. Back up and give me those last three again.”

“Sorry.” He took Rafferty's pencil and wrote down the three technical words. “âArrhythmia' is any disturbance in the rhythm of the heartbeat: âFibrillation' is when the heart muscle stops contracting and merely quivers, making ineffectual wormlike motions, and the blood doesn't get pumped around: And âsyncope' is fainting due to lack of blood getting to the brain.”

“And all these developments are bad?”

“Very.” He nodded.

Rafferty was thoughtful. “If someone knew this woman's medical history, could any of these disturbances be artificially induced, by, say, the introduction of a drug?”

Fenimore looked up. “You think her death was unnatural?”

“Her burial sure was.”

“Not for a Native American.”

“Come on, Doc. How many Native Americans bury their friends and relatives in vacant lots?”

“That âvacant lot' happens to be a sacred Lenape burial ground. But you have a point. It's been neglected and it's unprotected. A Lenape would not be likely to use it, unless ⦔

“Unless?”

“Unless they wanted the body to be found.”

Rafferty pondered this, drumming his fingers on the desk. Then he said, “Another thing. If this was a traditional Lenape burial, why didn't the family lay her out in something more appropriateâsome kind of ceremonial dress? She was wearing jeans, a T-shirt, and sandals.”

“True. But not all Lenapes own ceremonial garments. The

younger ones may have lost or discarded them, the way we might give our grandmother's wedding dress to a thrift shop or rummage sale.”

younger ones may have lost or discarded them, the way we might give our grandmother's wedding dress to a thrift shop or rummage sale.”

“Yours, maybe. If I did that, my grandma would come down and haunt me 'til I bought it back.” Rafferty had been pacing the office; now he turned on Fenimore. “And if this was a simple family burial, how do you account for someone bashing you on the head? Is that a quaint Lenape family custom too?”

“Totally unrelated. Some muggerâ”

“Who left a wallet behind with two hundred bucks.”

“He might have been interrupted.”

“By what?”

“You.”

“And disappeared into thin air?”

“No, into the back of the hotel. I saw a man come out of there to dump some trash. It wasn't locked.”

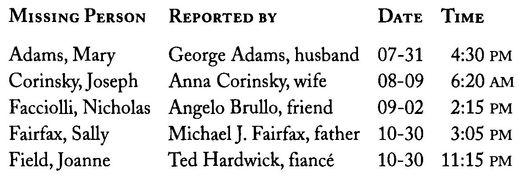

They sat in silence, glaring at each other. Finally Fenimore said, “Turn up anything in Missing Persons?”

“Thought you'd never ask.” Rafferty shot a computer printout across his desk.

Fenimore scanned the list:

He paused. There was a small penciled cross next to Field. “Let's see this description,” he pointed.

Rafferty had it ready. He passed it over.

JOANNE FIELD: Age: 24. Height: 5â²4â³. Weight: 118 lbs. Hair: Dark brown. Eyes: Dark brown. Race: Native American. Marks of identification: Scar transecting lower left quadrant of chest.

Fenimore raised his eyes to Rafferty's. “What are you waiting for?”

“A small canvas bag was found buried with her,” he said. “There were no obvious forms of identification in it, but the contents are being examined now and I'm waiting for the report.”

Fenimore pulled the list of missing persons toward him again and studied it. “I know a

Ned

Hardwick,” he said slowly.

Ned

Hardwick,” he said slowly.

Rafferty perked up. “Could this be his son?”

“Could be. Have you notified him yet?”

Other books

Dead in the Water by Ted Wood

If I Stay by Gayle Forman

Now and Forever by Danielle Steel

London Harmony: The Pike by Erik Schubach

The Ex-Boyfriend's Handbook by Matt Dunn

Making Angel (Mariani Crime Family Book 1) by Amanda Washington

One Night of Scandal by Elle Kennedy

Chained in the Demon's Lair (Hellfire Circus) by Crystal De la Cruz

True Colours by Fox, Vanessa