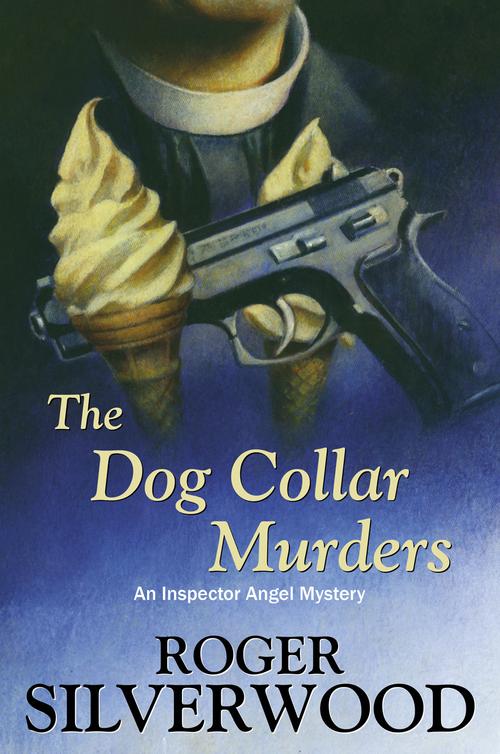

The Dog Collar Murders

Read The Dog Collar Murders Online

Authors: Roger Silverwood

An Inspector Angel Mystery

Roger Silverwood

9 a.m., Saturday, 9 January 2010

I

t was one of those days when the birds were coughing, the Rottweilers were barking and the police cars were screaming down the streets of Bromersley, while in the kitchen in St Joseph’s Vicarage, Bromersley, South Yorkshire, a brother and sister were having

breakfast

together.

‘Oh Tom, you’ll be the death of me,’ Phoebe Wilkinson said as she lowered her cup into the saucer. She snatched up a big black

shopping

bag from the floor at the side of her chair and rummaged around inside it. The bag was always with her, and was always full and bulging.

Tom Wilkinson put down his cup, reached out for the last piece of toast and said, ‘What are you looking for, Phoebe?’

‘My pen. I have a pen in here somewhere.’

‘Why do you want to hump that big bag of rubbish about with you everywhere you go? It’s twice as big as you are, and you can never find anything in there.’

She snorted and dug even deeper. ‘I have told you before that I have all my things in here … things that are important to me … things that I may want … at a moment’s notice.’

‘You know, Phoebe, I’m sure some of the congregation look at you and think you’re the vicar’s batty sister.’

Her nose was in the bag. She glanced out at him momentarily and said, ‘I’m too old to care what anybody thinks.’

‘I care. They are my people. They expect me to set them an example. They might start thinking that I’m batty too.’

She ignored him and continued to rummage.

‘What do you want a pen for?’ he said.

‘To write all this down. I shall never remember everything.’

‘Look, Phoebe, you needn’t worry. Elaine knows all about the arrangements. And the times and dates are in the diary.’

Her fists tightened but she soon released them. The arthritis in her fingers was painful that morning. ‘I don’t want to be dependent on somebody else

all

the time,’ she said. ‘I want to know it for myself.’

‘Well, borrow

my

pen.’

She waved him away. ‘I have my own pen in here somewhere,

and

my notebook.’

Phoebe Wilkinson almost turned the bag inside out to no avail, and then she suddenly found it, held it up and waved it at him, triumphantly. ‘I knew it was here.’

Then she returned to pushing the mish-mash of stuff around the bag again. A wrapped sweet, a single glove, a bottle of pills and a photograph of Frankie Dettori fell on to the carpet. She quickly rescued them and pushed them back in. Eventually she produced a small notebook. ‘There!’

Tom Wilkinson put the slice of buttered toast to his mouth and took a bite.

‘Now, when does the plane take off?’ she said.

‘Monday morning. I am taking the services here, tomorrow, as usual, of course, then on Monday at 10.15, Quentin is collecting me to take me to Leeds airport. I should be in Rome for teatime.’

She pulled a face like an alligator. ‘How very nice for you.’

‘You’ll be perfectly all right, Phoebe.’

‘It’s not right that you’re leaving me when winter is just setting in. And Rome is such a long way away.’

‘It’s my work, Phoebe. The bishop wants me to go to represent him. There are all sorts of meetings and discussions over there he wants me to attend. And it will be the last opportunity I shall have before I retire.’

She sniffed then said, ‘With champagne receptions in noble palaces, I expect.’

‘Some of those too, I hope. Now don’t be difficult, dear. You are going to be perfectly all right. I have tried to anticipate all eventualities. I have arranged for Elaine to come in

every

day, and Quentin to pop in about seven o’clock daily to check that you’re all right and to lock the door.’

‘What if I go dizzy again and have one of my falls?’

‘You’ve got your personal alarm phone. You know exactly what to do. I’ve been through it often enough with you. You press the button, there’s a nurse on duty at the other end 24/7 as they say. You just tell her what the trouble is.’

‘And what if your plane crashes? What am I going to do then?’

‘It won’t crash and if it did, I’d be in paradise a bit early, that’s all. You’d

still

be all right. Everything is in order.’

‘Huh. I don’t want to have to deal with the solicitors. They don’t speak intelligible English any more. And what if they sell The Grange?’

‘I am only going for two weeks. It’ll keep while I get back.’

‘When will I be able to get my share of the money?’

He glanced up momentarily at the ceiling. ‘You’re always on about that. Soon. Very soon. As soon as a purchaser has completed. And I shall pay Elaine before I go, so you won’t have anything to pay out.’

She glared up at him. ‘I haven’t

got

anything to pay out

with

. You’ve got it all. I ought to have

some

thing in my purse.’

‘Don’t let’s go through all that again. I put it in the bank for you. You know that you just lose money. And you don’t know what you’ve done with it. And you’ve nothing to show for it. It’s happened so many times.’

‘It’s just my memory, Tom. That’s all. I don’t remember things.’

‘Well … remember to be nice to young Robin Roebuck, if you see anything of him. He’ll be taking some of my services. He’ll be returning those vestments he borrowed. Tell Elaine some of them might need laundering. The thing is, just keep everything ticking over until I get back.’

She looked down at the carpet and shaking her head said, ‘I can’t keep answering the phone, Tom. I don’t know what to say to people. They say they know me but I have no idea who they are. And

sometimes

it rings all evening.’

‘Everybody wanting me will know that I’m away, Phoebe. There was a piece about it in the magazine, on the pew sheets and I mentioned it in the notices. Anybody who rings up, just tell them I’m away and give them Robin Roebuck’s number, that’s all.’

‘As long as it doesn’t ring during

Casualty

.’

He looked at his watch, then stood up. ‘Gone nine. Must get cracking, sis. I’ve morning prayers in fifty-eight minutes, and I haven’t prepared a thing.’

He went out.

She drained the cup of the last drop of tea. Then she pushed hard on the arms of the carver and stood precariously holding on to the table. She looked round, then bent down to pick up the black bag. By leaning on furniture and grabbing strategically placed handles, she made her way to the door into the hall and through another door into the sitting room. She was making her way across the room when she heard the front door slam shut. She stopped abruptly and looked back.

A voice called out, ‘It’s only me, Miss Wilkinson. It’s Elaine. Where are you?’

‘In here,’ she called. ‘Sitting room, dear.’

A young woman in a blue overall came in, looked across at her, smiled and said, ‘What are you trying to do?’

‘Get to my chair.’

Elaine put a hand under Phoebe Wilkinson’s arm and supported her to the electrically operated lounger chair by the fireplace. She lowered her into it and then handed her the control panel.

‘There you are,’ Elaine said. ‘Now I’ll get you a nice hot water bottle.’

‘Thank you, dear. No rush,’ she said as she pressed a button on the control panel which started the buzz of a small motor in the chair and caused the leg rest to rise slowly. When it reached a comfortable position, she stopped pressing the button, put the control on the chair arm, straightened her dress, looked up at Elaine and said, ‘Did you have a nice evening then?’

‘Yes, thank you, Miss Wilkinson. Did you?’

‘The usual. At my age, Elaine, one vicarage dinner with your brother and the church wardens and their wives is pretty well much like another.’

Elaine spotted a copy of the local newspaper on top of other papers and magazines on the little table at the side of the chair. ‘You’ve read the

Chronicle

then? I looked for The Grange again but it is not advertised. It

must

have been sold.’

Phoebe Wilkinson blinked. Her face brightened. ‘Do you think so?’

‘Most likely.’

She smiled. ‘Half of that money is mine, you know.’

‘I hope they got a good price for you, Miss Wilkinson,’ Elaine said. ‘What are you going to do with your half?’

‘Not sure, Elaine. I’m really not sure. Haven’t made my mind up. There are so many good causes. My brother said we might have to take a low price because of the recession. But you know him, always the pessimist.’

Elaine’s eyes glowed. ‘Some people say the recession is over. I heard that some really good houses are fetching big money. Your father’s house is a lovely house in an expensive area. Probably fetched millions. Imagine all that money to do whatever you like with.’

Phoebe Wilkinson did not need Elaine to draw her any word pictures.

‘Whatever it is, imagine all that in cash,’ Elaine said.

Phoebe Wilkinson shook her head. ‘It’ll come in a cheque or a warrant or something like that, I suppose. It’ll just be so much paper.’

Elaine said, ‘I heard on the news that they’re talking about doing away with cheques? Some shops won’t take them now. It’s back to old-fashioned cash. My father still buys everything with cash. Doesn’t have a bank account. Doesn’t trust banks. Is there any wonder? Well, who does

these

days, I ask you? Huh.’

‘Well, I haven’t a cheque book now,’ Phoebe Wilkinson said, then she shook her head. ‘Think of it. Had one since I was twenty-one. All those years, then last April, my brother wouldn’t let me replace it because I lost it between here and the chemists. If I want any money for anything now, I have to ask

him

for it.’

Elaine didn’t think that was right, but she knew that she oughtn’t to say so. She patted the old lady’s hand and said, ‘I’ll fill you a hot water bottle, Miss Wilkinson, then I’ll make you a

nice

cup of coffee.’

‘Lovely, dear. Thank you.’

Elaine went out and closed the door.

Phoebe Wilkinson half closed her watery blue eyes and slowly rubbed her chin. There was something on her mind. Something was troubling her. After a minute or so, she made a decision. She blinked

several times thoughtfully as she reached out for the phone book. She soon found the number she wanted and underlined it with her ballpoint pen. Then she reached out for the phone and tapped out the number. As it rang out, her lips moved silently as she rehearsed what she intended to say.

It rang for a long time and then it was answered by a man who sounded startled. ‘Er … hello?’

Phoebe Wilkinson frowned and said, ‘Is that Mace and Hall,

solicitors

?’

‘Well, yes, but the office is closed,’ the voice said. ‘It’s Saturday, you know. I wouldn’t normally be here. I just called in because I had forgotten something.’

‘I know it is Saturday, young man. Nevertheless, this is Miss Wilkinson here. Miss Phoebe Wilkinson, and as you happen to be there perhaps you would be kind enough to assist me?’

‘Oh, yes. Miss Wilkinson. If I can I will, Miss Wilkinson,’ the young man said.

‘Would you kindly tell me what progress you have made with the sale of my late father’s house, The Grange, Duxberry Road?’

‘Oh yes, Miss Wilkinson. Good morning to you. The Grange? Oh yes. In its own grounds. Natural lake. Five bedrooms. I remember. It’s not my department actually, but I seem to remember that there was a lot of interest shown in it. At the price, it is rather an

exclusive

property … and there are not many potential buyers who have immediate access to that amount of ready cash in this financial climate. They may be in the process of trying to raise the money from the banks or building societies. This snow and ice and bad weather may have slowed down people’s intentions. Though it might be getting warmer soon.’

‘I don’t want a weather forecast, young man. I simply want to know if it is sold. Can you please confirm

that

for me?’

‘I really don’t know, Miss Wilkinson.’

‘It

could

be, then?’

‘Oh yes. If it was a cash sale it very well could be.’

‘A

cash

sale? I see. Ah well, how soon could I expect to receive payment?’

‘We don’t hang on to clients’ funds longer than necessary, Miss Wilkinson. In such circumstances, fees and disbursements are

quickly worked out and deducted and the balance paid out by our cashier in a very few days.’

‘A few days?’

‘Earlier if there were special circumstances.’

‘Yes, well, please tell your cashier there

are

special circumstances …’

‘I certainly will, Miss Wilkinson.’

30 Park Street, Forest Hill Estate, Bromersley, South Yorkshire, UK.

7.10 a.m., Monday, 11 January 2010

Detective Inspector Angel was at the bathroom sink lathering up his face with a new badger-hair shaving brush he had had bought for Christmas.

His wife Mary came into the bathroom with an opened letter in her hand.

‘Michael,’ she said, rubbing her temple, ‘I have been reading that letter from Lolly again.’

He squinted at the mirror. References to Lolly, Mary’s sister, tended to irritate him. She reminded him of a butterfly that fluttered about the place seemingly unable to decide where to land and when it did, it settled by a burning flame and singed a wing.

He picked up the razor, rinsed it under the hot tap and applied it to his lathered cheek.

‘Can I read the bit I mean?’ Mary said.

His eyebrows went up. ‘Do I have a choice?’

She glared at him momentarily and then looked down at the letter. ‘It’s the last bit. She says, “Mary, darling, you are my only sister and we used to be so close. We had such fun. Do you remember when we all used to go to Grandpa’s in the summer and stay for simply ages? You and I used to go down to the pond and paddle and fish and sunbathe. That’s where we met the Simpson boys. Barnaby had a crush on you. And Nigel had the hots for me. Happy days! I know that I miss you terribly. I would love for us to spend some time together again. We could have a really great time when Michael is at the office doing his murders and things. It would be simply great if we could get together again. I would love to come over and see you.

I hear there are some great shops in Leeds these days. I wonder what happened to Nigel. As it happens, my apartment is being decorated the first two weeks in January and will pong of fresh paint for a week or two after that. If you could do with me about then, it would be great. We haven’t seen each other since Pa’s funeral, and I haven’t seen you since you moved into your new bungalow. It would be great to give you a big hug. And Michael, of course. Lots of kisses. Love you. Lolly.”’