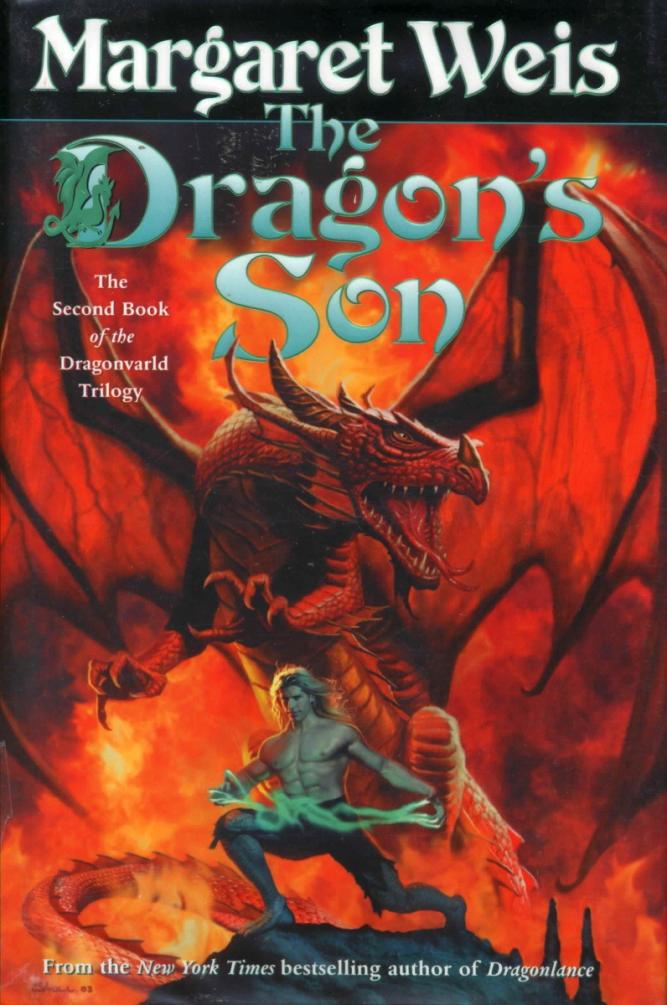

The Dragon's Son

Authors: Margaret Weis

The Dragon’s Son

Dragonvarld Book 2

Margaret Weis

To Bayne and Bette Perrin, with a

daughter’s love and respect

MELISANDE CLOSED HER EYES. SHE DREW IN A LABORED

breath, breathed

it out in a sigh. The twisted grimace of pain relaxed, smoothed. Her head

lolled on the pillow. Her eyes opened, stared at Bel-lona, but they did not see

her. Their gaze was fixed and empty.

Bellona gave an anguished cry.

Beneath the bed, the two babies lay in a pool of their mother’s blood and

wailed as if they knew.

Melisande’s sons.

One of them human, born of love and magic.

One of them half-human and half-dragon, born of evil.

Both of them hidden away. One in plain view for all the world to see. One in

the tangled forest of a grieving and embittered heart.

None of this had turned out as any of the dragons

had planned.

“Killing the mother was folly,” raved Grald, the dragon father of the

half-human son. “Your women were supposed to capture her, bring her to me. She

was unusually strong in the dragon magic, as proven by the fact that she bore

my son and both she and the babe survived. I could have continued to make use

of her, to breed more like her.”

“You have found others who are serving the same purpose. As for Melisande,

she

was

unusually strong,” Maristara stated coldly. “The threat she

posed far outweighed her usefulness. She was the sole human on this earth who

knew the truth about the Mistress of Dragons.”

“A threat she posed to you,” Grald grumbled.

“A threat to me is a threat to us both,” Maristara returned. “Without the

children of Seth, you would have no city, no subjects, no army.”

“We do not yet have an army.”

“We will. Our plans can go forward now that Melisande has been removed,”

said Maristara, with a dig and a twist of a mental claw.

“What about the Parliament?”

“The Parliament of Dragons will do what it has done for a thousand years.

Talk and debate. Decide not to decide. Then fly back to their safe and secret

lairs and go to sleep.”

“And the walker. Draconas.” Grald growled the name and mumbled over it, as

if it were a bone the dragon would like very much to chew. “You must concede

that he is—or could be—a threat.”

“That is true and we will deal with him, but all in good time. As he so

cleverly arranged it, he is our only link to the children— the sons of

Melisande. Your son in particular. Kill him and we kill any chance of finding

them. Besides, if he were to suddenly turn up dead, think of the uproar. The

Parliament might actually be inclined to do something. Best to lull them into

complacency. Let the Parliament slumber and let Draconas walk the world on his

two human legs.”

“So long as we keep track of where those human legs of his take him,” said

Grald.

“That is a given,” agreed Maristara.

Draconas heard two babies crying. Not an unusual sound for human ears to

hear, for every second that passed on earth was heralded by a baby’s cry, as

some woman somewhere brought forth new life. The cries of babies might be said

to be the song of the stars.

What was unusual was that Draconas—the walker, the dragon who had taken

human form—heard the cries of these two babies in his mind. The babes

themselves were far away, but the dragon blood in both linked them, all three,

together.

He stood beside the cairn he had raised over the body of their mother and

listened to the wails and spoke to her, who would never hear the cries of those

she had brought into the world.

“There are some of my kind who believe it would have been better if your

children were now lying dead in your arms, Melisande. Better for us. Better for

them. In that instance, we dragons could yawn and roll over and go back to

sleep and wake again in a thousand years. But, the children lived and so does

the danger from those who brought all this about. We dragons must remain awake

and vigilant. Your children were born of blood and death, Melisande, and I

believe that is a portent.”

He placed his hand upon the cold stone and wrote in

flames of magic the words:

Melisande

Mistress of Dragons

Picking up his walking staff, Draconas left the

tomb. The cries of the babies sounded loud in his mind until each fell asleep,

and the wails died away.

BELLONA SENT THE BOY OUT TO CHECK HIS RABBIT SNARES. THIS was one chore he

never minded, for he was always hungry. When he found that he’d caught nothing,

he was only mildly disappointed. He did not have to worry about his next meal

this day. Bellona had brought down a fat doe the week before and there would be

fresh meat in the house for some time to come. His mind was not on food. Today

was the boy’s birthday and he was preoccupied with the memory of what had

happened this morning.

He’d experienced five birthdays up to now. Today made the sixth. He

remembered clearly his last three birthdays and he might have been able to remember

the birthday before that, but he could not be certain if he was actually

remembering the birthday or if he had formed the memory out of those birthdays

that had come since.

The boy dreaded his birthday and looked forward to it, all at the same time.

He dreaded the day for the awful solemnity that attended it. He looked forward

to the day, too, for on his birthday, Bellona would sit him down and speak with

him directly, an unusual occurrence. There were just the two of them—the boy

and the woman—but there was little communication between them. The two would

sometimes go for days without saying more than a few words to each other.

At night, especially in the winter, when darkness came so early that neither

of them was ready for sleep, Bellona would tell stories of ancient days,

ancient warriors, ancient battles, ancient honor and death. The boy never felt

as though she was talking to him when she told these stories, however. It was

more as if she was talking to them, those who had died. Either that, or talking

to herself, as if she was the same audience.

On his birthday, however, Bellona talked to him, to the boy, and although

the words were terrible to hear, he valued them and held them close to him all

the rest of the year, because on his day they were his words and belonged to no

one else.

The boy had an imperfect sense of time. He had no need to count the days or

months and he remembered the years only because of this one day. He and Bellona

lived deep within the forest, isolated and alone, just the two of them. The

passage of time for the boy was marked by gentle rain and the return of

birdsong, the hot sun of summer, falling leaves, and, after that, snow and

bitter cold. Bellona counted the days, however, and he always knew when his

birthday was coming, for she would begin to make ready their dwelling in order

to receive the special guest.

Bellona always kept the dwelling neat, for she could not abide disorder. She

kept their dwelling in repair, working to make it dry during the spring rains

and the summer thunder and warm during the harsh winter. Beyond that, she paid

scant attention to it, for she was rarely inside it. Four walls stifled her,

she said. She could not breathe inside them. She would often sleep outside,

wrapped in her blanket, lying across the door.

The boy slept inside. He had a liking for walls and a roof and snug

darkness. His favorite place in the world, apart from their dwelling, was a

cave he had discovered located about a half mile from the dwelling. He visited

the cave often, whenever he could escape from his chores. He felt safe in the

cave, secure, and he would come there to hide away. He had come to the cave

now, to think about his birthday.

Yesterday, the day before his birthday, Bellona swept the floor of their

one-room hut, then laid down the fresh green rushes he’d gathered from the

marsh. She cleaned the ashes from the fireplace and sent him to the stream to

wash up the two wooden bowls and two horn spoons, the two eating knives and the

two pewter mugs. She shook the dried grass out of the pallet on which he slept

and burned it and stuffed it with fresh. She cleared away her tools and the

arrows she had been tying from the table, which was one of only three pieces of

handmade furniture in the hut. The furniture was not very well made. She was a

warrior, she said, not a carpenter. The table wobbled on uneven legs. There was

a tipsy chair for her and a low stool for him, a stool that he was fast

outgrowing.

Her cleaning done, Bellona stood inside the small hut, her hands on her

hips, and looked around with satisfaction.

“All is ready for you, Melisande,” Bellona said. “We are here.”

That night, the night before his birthday, Bellona remained inside the hut,

keeping watch. Whenever he woke, which was often, for he was too nervous to

sleep, he saw her lying on her side, her dark eyes fixed on the dying embers,

the embers glowing in her eyes.

That morning, first thing, she sent him out to gather flowers. He knew how

important the flowers were to her and they had become important for him, too,

as being part of the ritual of this day, and he had taken to searching out

places where grew the spring wildflowers, in order that he would be prepared.

He brought back two fistfuls of the bright blue flowers known by the

peculiar name of squill, some dogtooth violets and bleeding heart. He gave them

to Bellona, who dunked them in one of the two bowls that she had filled with

water. She then set the flowers on the table, and sat in the chair. He squatted

on his stool. His claws scraped the floor nervously, bruising the rushes and

filling the air with a sweet smell of green and growing things. Bellona looked

at him, also something special. On other days, she cast him a glance now and

then and only when necessary. The sight of him pained her. He had once assumed

he knew why she couldn’t stand to look at him, but he had found out on his last

birthday that he’d been wrong.

She would look at him today. She would also touch him. Her look and her

touch made this day doubly special, doubly awful. He waited, tensely, for the

moment.

“Enter, Melisande. You are welcome,” Bellona called. The first rays of the

morning sun slid in through the chinks in the wooden logs and stole in through

the open door. “You have come to see your son and here he is, waiting to do you

honor.

“Ven.” Bellona turned her gaze full upon him. “Come to me. Let your mother

see how you have grown.”

Yen’s mother, Melisande, was dead. She had died on the day of his birth. Her

death and his birth were tangled together, though Ven did not understand how.

He knew better than to ask. He had learned, long ago, that Bellona had little

patience for questions.

Ven stood up. His claws made scraping noises as he walked across the dirt

floor and he was conscious of the sounds his claws made in the silence that was

fragrant, smelled of the flowers and the bruised rushes. He was conscious of

the sound because he knew Bellona was conscious of it. On this day she heard

it, when on other days she could ignore it.

Ven saw himself reflected in her dark eyes, the only time in the year he

would ever see himself there. He saw a face that was much like the face of

other children, except that his face had forgotten how to smile. He saw blue

eyes that were fearless, for Bellona had taught him that fear was something he

must master. He saw fair hair that his mother cut short, hacking savagely at it

with her knife, as if it hurt her. He saw the arms of a child, stronger than

most, for he was expected to earn his way in the world. He saw the body of a

child, slender now that he had lost his baby fat, his ribs visible beneath

sun-browned skin.

And he saw, in her eyes, his legs. His legs were not the legs of any human

child ever born upon this earth. His legs, from the groin down, were the legs

of a beast—hunched at the knee, covered all over in glittering blue scales; his

long toes ending in sharp claws.

Ven walked up to Bellona. She rested her hands on his shoulders, and pinched

them hard, to make him stand as straight as he could, given his hunched legs.

She reached out a hand that was callused and rough to brush the fair hair out

of his eyes. She looked at him, looked at him long, and he saw pain twist her

stern mouth and deepen the darkness of her eyes.

“Here is your boy, Melisande. Here is Ven. Bid your mother greeting, Ven.”

“Greeting, Mother,” said Ven, low and solemn.

“This day six years ago you were born, Ven,” said Bellona. “For you, this

day began in blood and ended in fire. For your mother, this day began in pain

and ended in death. I promised her, as she lay dying on this day, six years

ago, that I would take her son and raise him and keep him safe. You see,

Melisande, that I have kept my vow.”