The Driver's Seat

Authors: Muriel Spark

THE

DRIVER’S SEAT

Muriel Spark

ONE

‘And the material doesn’t

stain,’ the salesgirl says.

‘Doesn’t

stain?’

‘It’s

the new fabric,’ the salesgirl says. ‘Specially treated. Won’t mark. If you

spill like a bit of ice-cream or a drop of coffee, like, down the front of this

dress it won’t hold the stain.’

The

customer, a young woman, is suddenly tearing at the fastener at the neck,

pulling at the zip of the dress. She is saying, ‘Get this thing off me. Off me,

at once.

The

salesgirl shouts at the customer who, up to now, has been delighted with the

bright coloured dress. It is patterned with green and purple squares on a white

background, with blue spots within the green squares, cyclamen spots within the

purple. This dress has not been a successful line; other dresses in the new

stainless fabric have sold, but this, of which three others, identical but for

sizes, hang in the back storeroom awaiting the drastic reductions of next week’s

sale, has been too vivid for most customers’ taste. But the customer who now

steps speedily out of it, throwing it on the floor with the utmost irritation,

had almost smiled with satisfaction when she had tried it on. She had said, ‘That’s

my dress.’ The salesgirl had said it needed taking up at the hem. ‘All right,’

the customer had said, ‘but I need it for tomorrow.’ ‘We can’t do it before

Friday, I’m sorry,’ the salesgirl had said. ‘Oh, I’ll do it myself, then,’ the

customer had said, and turned round to admire it sideways in the long mirror. ‘It’s

a good fit. Lovely colours,’ she said.

‘And it

doesn’t stain,’ the salesgirl had said, with her eye wandering to another

unstainable and equally unsaleable summer dress which evidently she hoped, now,

to offer the satisfied customer.

‘Doesn’t

stain?’

The

customer has flung the dress aside.

The

salesgirl shouts, as if to assist her explanation. ‘Specially treated fabric… If you spill like a drop of sherry you just wipe it off. Look, Miss, you’re

tearing the neck.’

‘Do you

think I spill things on my clothes?’ the customer shrieks. ‘Do I look as if I

don’t eat properly?’

‘Miss,

I only remarked on the fabric, that when you tell me you’re going abroad for

your vacation, there is always the marks that you pick up on your journey. Don’t

treat our clothes like that if you please. Miss, I only said stain-resisting

and then you carry on, after you liked it.’

‘Who

asked you for a stain-resisting dress?’ the customer shouts, getting quickly,

with absolute purpose, into her own blouse and skirt.

‘You

liked the colours, didn’t you?’ shouts the girl. ‘What difference does it

make, so it resists stains, if you liked the fabric before you knew?’

The

customer picks up her bag and goes to the door almost at a run, while two other

salesgirls and two other customers gasp and gape. At the door she turns to look

back and says, with a look of satisfaction at her own dominance over the

situation with an undoubtable excuse, ‘I won’t be insulted!’

She walks along the broad

street, scanning the windows for the dress she needs, the necessary dress. Her

lips are slightly parted; she, whose lips are usually pressed together with the

daily disapprovals of the accountants’ office where she has worked continually,

except for the months of illness, since she was eighteen, that is to say, for

sixteen years and some months. Her lips, when she does not speak or eat, are

normally pressed together like the ruled line of a balance sheet, marked

straight with her old-fashioned lipstick, a final and a judging mouth, a

precision instrument, a detail-warden of a mouth; she has five girls under her

and two men. Over her are two women and five men. Her immediate superior had

given her the afternoon off, in kindness, Friday afternoon. ‘You’ve got your

packing to do, Lise. Go home, pack and rest.’ She had resisted. ‘I don’t need a

rest. I’ve got all this work to finish. Look — all this.’ The superior, a fat

small man, looked at her with frightened eyeglasses. Lise smiled and bent her

head over her desk. ‘It can wait till you get back,’ said the man, and when she

looked up at him he showed courage and defiance in his rimless spectacles. Then

she had begun to laugh hysterically. She finished laughing and started crying

all in a flood, while a flurry at the other desks, the jerky backward movements

of her little fat superior, conveyed to her that she had done again what she

had not done for five years. As she ran to the lavatory she shouted to the

whole office who somehow or other were trying to follow or help her. ‘Leave me

alone! It doesn’t matter. What does it matter?’ Half an hour later they said, ‘You

need a good holiday, Lise. You need your vacation.’ ‘I’m going to have it,’ she

said, ‘I’m going to have the time of my life,’ and she had looked at the two

men and five girls under her, and at her quivering superior, one by one, with

her lips straight as a line which could cancel them all out completely.

Now, as

she walks along the street after leaving the shop, her lips are slightly parted

as if to receive a secret flavour. In fact her nostrils and eyes are a fragment

more open than usual, imperceptibly but thoroughly they accompany her parted

lips in one mission, the sensing of the dress that she must get.

She

swerves in her course at the door of a department store and enters. Resort

Department: she has seen the dress. A lemon-yellow top with a skirt patterned

in bright V’s of orange, mauve and blue. ‘Is it made of that stain-resisting

material?’ she asks when she has put it on and is looking at herself in the

mirror. ‘Stain-resisting? I don’t know, Madam. It’s a washable cotton, but if I

were you I’d have it dry-cleaned. It might shrink.’ Lise laughs, and the girl

says, ‘I’m afraid we haven’t anything really stain-resisting. I’ve never heard

of anything like that.’ Lise makes her mouth into a straight line. Then she

says, ‘I’ll have it.’ Meanwhile she is pulling off a hanger a summer coat with

narrow stripes, red and white, with a white collar; very quickly she tries it

on over the new dress. ‘Of course, the two don’t go well together,’ says the

salesgirl. ‘You’d have to see them on separate.’

Lise

does not appear to listen. She studies herself. This way and that, in the

mirror of the fitting room. She lets the coat hang open over the dress. Her

lips part, and her eyes narrow; she breathes for a moment as in a trance.

The

salesgirl says, ‘You can’t really see the coat at its best, Madam, over that

frock.’

Lise

appears suddenly to hear her, opening her eyes and closing her lips. The girl

is saying, ‘You won’t be able to wear them together, but it’s a lovely coat,

over a plain dress, white or navy, or for the evenings …’

‘They

go very well together,’ Lise says, and taking off the coat she hands it

carefully to the girl. ‘I’ll have it; also, the dress. I can take up the hem

myself.’ She reaches for her blouse and skirt and says to the girl, ‘Those

colours of the dress and the coat are absolutely right for me. Very natural

colours.’

The

girl, placating, says, ‘Oh, it’s how you feel in things yourself, Madam, isn’t

it? It’s you’s got to wear them.’ Lise buttons her blouse disapprovingly. She

follows the girl to the shop-floor, pays the bill, waits for the change and,

when the girl hands her first the change then the large bag of heavy paper

containing her new purchases, she opens the top of the bag enough to enable her

to peep inside, to put in her hand and tear a corner of the tissue paper which

enfolds each garment. She is obviously making sure she is being handed the

right garments. The girl is about to speak, probably to say, ‘Everything all

right?’ or ‘Thank you, Madam, goodbye,’ or even, ‘Don’t worry; everything’s

there all right.’ But Lise speaks first; she says, ‘The colours go together

perfectly. People here in the North are ignorant of colours. Conservative;

old-fashioned. If only you knew! These colours are a natural blend for me.

Absolutely natural.’ She does not wait for a reply; she does not turn towards

the lift, she turns, instead, towards the down escalator, purposefully making

her way through a short lane of dresses that hang in their stands.

She

stops abruptly at the top of the escalator and looks back, then smiles as if

she sees and hears what she had expected. The salesgirl, thinking her customer

is already on the escalator out of sight, out of hearing, has turned to another

black-frocked salesgirl. ‘All those colours together!’ she is saying. ‘Those

incredible colours! She said they were perfectly natural. Natural! Here in the

North, she said …’ Her voice stops as she sees that Lise is looking and

hearing. The girl affects to be fumbling with a dress on the rack and to be

saying something else without changing her expression too noticeably. Lise

laughs aloud and descends the escalator.

‘Well, enjoy yourself

Lise,’ says the voice on the telephone. ‘Send me a card.’

‘Oh, of

course,’ Lise says, and when she has hung up she laughs heartily. She does not

stop. She goes to the wash-basin and fills a glass of water, which she drinks,

gurgling, then another, and still nearly choking she drinks another. She has

stopped laughing, and now breathing heavily says to the mute telephone, ‘Of

course. Oh, of course.’ Still heaving with exhaustion she pulls out the hard

wall-seat which adapts to a bed and takes off her shoes, placing them beside

the bed. She puts the large carrier-bag containing her new coat and dress in a

cupboard beside her suitcase which is already packed. She places her hand-bag

on the lamp-shelf beside the bed and lies down.

Her

face is solemn as she lies, at first staring at the brown pinewood door as if

to see beyond it. Presently her breathing becomes normal. The room is

meticulously neat. It is a one-room flat in an apartment house. Since it was

put up the designer has won prizes for his interiors, he has become known

throughout the country and far beyond and is now no longer to be obtained by

landlords of moderate price. The lines of the room are pure; space is used as a

pattern in itself, circumscribed by the dexterous pinewood outlines that ensued

from the designer’s ingenuity and austere taste when he was young, unknown,

studious and strict-principled. The company that owns the apartment house knows

the worth of these pinewood interiors. Pinewood alone is now nearly as scarce

as the architect himself, but the law, so far, prevents them from raising the

rents very much. The tenants have long leases. Lise moved in when the house was

new, ten years ago. She has added very little to the room; very little is

needed, for the furniture is all fixed, adaptable to various uses, and

stackable. Stacked into a panel are six folding chairs, should the tenant

decide to entertain six for dinner. The writing desk extends to a dining table,

and when the desk is not in use it, too, disappears into the pinewood wall, its

bracket-lamp hingeing outward and upward to form a wall-lamp. The bed is by day

a narrow seat with overhanging bookcases; by night it swivels out to

accommodate the sleeper. Lise has put down a patterned rug from Greece. She has

fitted a hopsack covering on the seat of the divan. Unlike the other tenants

she has not put unnecessary curtains in the window; her flat is not closely

overlooked and in summer she keeps the venetian blinds down over the windows

and slightly opened to let in the light. A small pantry-kitchen adjoins this

room. Here, too, everything is contrived to fold away into the dignity of

unvarnished pinewood. And in the bathroom as well, nothing need be seen,

nothing need be left lying about. The bed-supports, the door, the window frame,

the hanging cupboard, the storage space, the shelves, the desk that extends,

the tables that stack — they are made of such pinewood as one may never see

again in a modest bachelor apartment. Lise keeps her flat as clean-lined and

clear to return to after her work as if it were uninhabited. The swaying tall

pines among the litter of cones on the forest floor have been subdued into

silence and into obedient bulks.

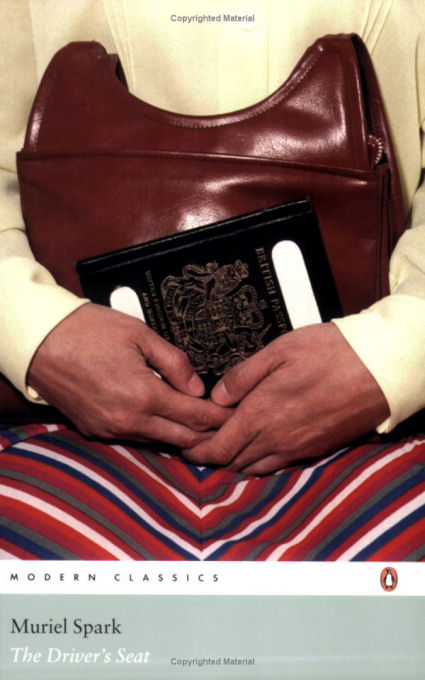

Lise

breathes as if sleeping, deeply tired, but her eye-slits open from time to

time. Her hand moves to her brown leather bag on the lamp-shelf and she raises

herself, pulling the bag towards her. She leans on one elbow and empties the

contents on the bed. She lifts them one by one, checking carefully, and puts

them back; there is a folded envelope from the travel agency containing her air

ticket, a powder compact, a lipstick, a comb. There is a bunch of keys. She

smiles at them and her lips are parted. There are six keys on the steel ring,

two Yale door-keys, a key that might belong to a functional cupboard or drawer,

a small silver-metal key of the type commonly belonging to zip-fastened

luggage, and two tarnished car-keys. Lise takes the car-keys off the ring and

lays them aside; the rest go back in her bag. Her passport, in its transparent

plastic envelope, goes back in her bag. With straightened lips she prepares for

her departure the next day. She unpacks the new coat and dress and hangs them

on hangers.