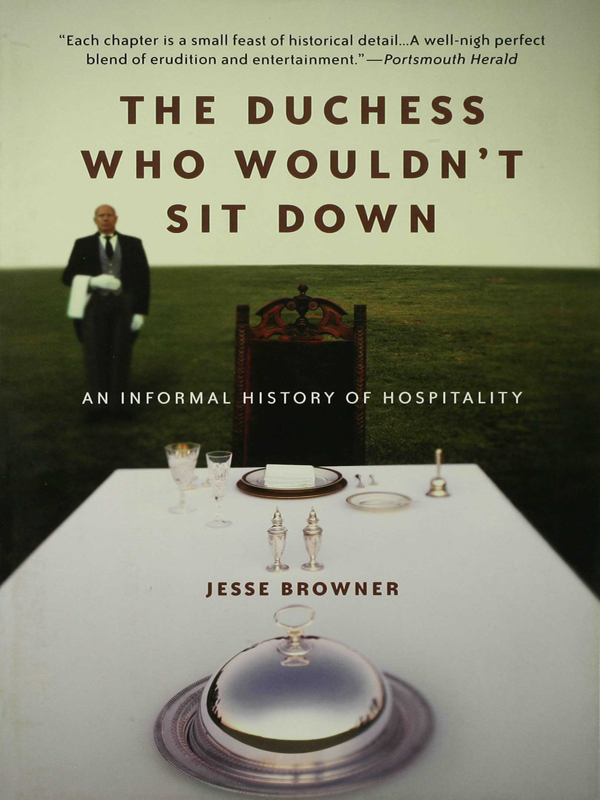

The Duchess Who Wouldn't Sit Down

Read The Duchess Who Wouldn't Sit Down Online

Authors: Jesse Browner

THE DUCHESS

WHO WOULDN'T

SIT DOWN

THE DUCHESS

WHO WOULDN'T

SIT DOWN

AN INFORMAL HISTORY OF HOSPITALITY

JESSE BROWNER

BLOOMSBURY

Copyright © 2003 by Jesse Browner

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from

the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury

Publishing, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury Publishing, New York and London

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Bloomsbury Publishing are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The

manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Browner, Jesse, 1961-

The duchess who wouldn't sit down : an informal history of hospitality / Jesse Browner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-1-1-59691-728-6

1. Hospitality—History. I. Title.

BJ2021.B76 2003

395.3'09—dc22

2003045134

First published in hardcover by Bloomsbury Publishing in 2003 This paperback edition published in 2004

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Hewer Text Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the United States of America

by Quebecor World Fairfield

For Cora, Sophie, and Judy

CONTENTS

I. How to Put Your Guests at Ease

IV. The Duchess Who Wouldn't Sit Down

Good things are for good people; otherwise we should be reduced to the

absurd belief that God created them for sinners.

Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin,

The Physiobgy of Taste

Not long ago, I sat down to a game of poker with five old friends. About an hour into the game, long before the heavy betting

began, Guy rose from the table to help himself to a sandwich from a tray I had set out earlier. He heaped some chips onto

the side of his plate, grabbed a beer from the refrigerator, and returned to his place as a hand of stud was being dealt.

From the corner of my eye, I watched as he retrieved his cards with his right hand and his sandwich with his left. He studied

the cards as he brought the sandwich to his mouth and bit into it. An instant later, he glanced with apparent surprise and

pleasure at the sandwich, then, surreptitiously, at me. He muttered something unintelligible and sheepishly returned his gaze

to the cards.

I smiled to myself. He had paid me a high, if silent, compliment. More important, though, his ill-concealed embarrassment

had told me everything I needed to know about the strength of his cards. Less than a minute later, with only a pair of fours

in my hand, I bluffed him out of twenty-three dollars.

I have been playing in the same floating poker game for about twelve years. Most of us went to college together, but we no

longer have much in common other than our shared history and our love of poker. We were all single when the game began. Three

of us are married now; some have children; some make more money than others. We often go months without seeing each other

anywhere beyond the card table. The years have accentuated our differences; poker annihilates them. When I sit down on a Sunday

night for six hours of card play with these men, I feel that I know them as well as I know anyone in the world. That, of course,

is an illusion, but, like so much else in poker, a useful one.

The sandwiches I had prepared were no ordinary sandwiches. They had been assembled out of fresh rolls from a hundred-year-old

Portuguese bakery in Connecticut; a brisket braised for more than four hours; and a horseradish sauce prepared from a secret

recipe. The dish was one in a repertoire of meals I've developed specifically for poker games over the past twelve years.

Cooking for card players is governed by a slew of constraints, but you can still be extremely creative and bring a delicate

touch to it, if you're motivated to do so. The question is: What could possibly motivate you to do so? Why bother with such

hyperactive hospitality when far less would do? It's a question I've been asking myself for a number of years.

No one could argue against the basic premise that when you cook for someone you seek to please them. It would seem self-evident

that a guest's satisfaction must be the only response acceptable to an attentive host. "To entertain a guest is to make yourself

responsible for his happiness so long as he is beneath your roof," says Brillat-Savarin in

The Physiology of Taste.

That sentence embodies the very essence of the traditional view of hospitality and its obligations. But of course, nothing

- not even happiness - is ever as simple as it seems. Epicurus, for starters, defines two essential types of pleasure: the

"moving" pleasure of fulfilling a desire and the far superior "static" pleasure of being in a state of satiety. When you eat

my good food, you are happy; but when you are full of my good food, you are in a state of

ataraxia

- tranquility or serenity - that tends to overwhelm or dampen your other desires, including, perhaps, your impulse to fleece

or humiliate me at the poker table.

Here is Brillat-Savarin's description of the effect of a well-prepared Barbezieux cockerel on his guests: "I saw successively

imprinted on every face the glow of desire, the ecstasy of enjoyment, and the perfect calm of utter bliss" - an uncannily

accurate demonstration and proof of Epicurus' thesis. Now, it goes without saying that the perfect calm of utter bliss is

not a condition in which you want to be when risking the month's rent in a game of aggression, guile, and chance. So, I reasoned

to myself, if my lamb-salad hero had even half the ataractic effect of the Barbezieux cockerel, I would be unbeatable.

And so it has proven. Offered in apparent generosity and selflessness - one old and trusted friend to another - my hospitality

is in fact a Trojan horse, fatally compromising my rivals' defenses from within. I watch my opponents eat; they smile, they

stretch, they grow chatty and convivial. They let down their guard. I strike.

What is hospitality? That would seem to be a simple question with an equally simple answer. Some four thousand years ago,

an Akkadian father offered his son the following guidelines for hospitality: "Give food to eat, beer to drink, grant what

is requested, provide for and treat with honor." If anyone has ever written a better or more concise summary of the host's

duty, I have not read it. It is, of course, utterly delusional. Hospitality is a state of mind, not a prescriptive agenda,

and defining it is an extremely vexed proposition, like asking "What is art?" or "What is good parenting?" Such questions

are like the innocuous, unadorned entrance to a pyramid or a catacomb. We enter naively, at our own risk, and are immediately

lost. Three brief, relatively straightforward visions of hospitality are more than enough to illustrate just how daunting

the challenge might be:

(a)

The patriarch Abraham welcomes three travelers into his tent by the oaks of Mamre. He offers them water, lamb, bread, curds,

and milk and a place to rest and wash their feet. He asks nothing of them in return; requesting compensation would not be

hospitable. It is enough for Abraham that strangers require food and water and that he is able and willing to provide it.

That has always been the accepted version of hospitality, extended for its own sake and without ulterior motive, except perhaps

for the reasonable hope that it will be extended in kind to you when you need it. But it becomes an entirely different story,

with an entirely different moral, when you know that Abraham recognized the travelers as angels

before

he invited them in. Abraham's hospitality, it seems, was little more than an insurance policy.

(b)

William McKay, played by Buster Keaton in

Our Hospitality,

returns to the home of his youth to claim his inheritance. A stranger in town, he is taken in by the wealthy Canfields, who

offer him food, clean clothing, and a room, simply because he is in need - the very epitome of Southern hospitality. But when

the Canfields discover he is a McKay, a member of the clan with which they have fought a generations-old feud, their only

thought is to get him out of their house as fast as possible. Why? Because they cannot bear having an enemy under their own

roof? No, it is because the rules of hospitality - which they, as honorable Southern gentlemen, must obey to the letter -

require the host to ensure that no harm comes to his guest. They can gun him down mercilessly the moment he crosses the threshold,

but they are too well bred to ask him to leave. McKay, naturally enough, opts to stay. For the hosts, all the vaunted splendor

of Southern hospitality boils down to nothing but a single, insuperable barrier to their desire; to the guest, it is a Chinese

finger cuff, binding him tighter to his foes the more he seeks to flee them.

(c)

Anyone who has ever studied accounting knows that hospitality is cited as a "specific threat" to the independence of auditors.

To an auditor, enjoying a simple meal or a weekend in the country in the wrong circumstances has become more perilous to his

or her reputation, credibility, and livelihood than cooking the books, lying to shareholders, or taking employment with the

federal government.

Insurance, straitjacket, specific threat - we have come a long, long way from Akkadia.

Once when I was a little boy, I was out to dinner with my father when I innocently expressed sympathy for a solitary diner

who, it seemed to me, looked a bit lonely eating all by himself. My father, who traveled frequently and often found himself

alone in distant cities, instantly bristled at the suggestion. Some people like to eat alone, he grumbled. Why should anyone

eating alone automatically be assumed to be lonely? In fact, he proposed, the best way to enjoy a good meal is alone and undistracted

by chitchat and other interruptions.

My father was sorely mistaken. Eating, and hospitality in general, is a communion, and any meal worth attending by yourself

is improved by the multiples of those with whom it is shared. Animals eat alone, but even then not always. The first thing

monkeys did when they became humans was to gather around the campfire to celebrate, perhaps a little prematurely. Nearly two

thousand years ago, Athenaeus of Naucratis, in his

Deipnosophistae,

explicitly equated solitary eaters with criminals ("solitary eater and housebreaker!"), and just this year, the historian

Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, in

Near a Thousand Tables,

echoed Athenaeus' condemnation almost word for word: "that public enemy, the solitary eater." The fact is, eating in groups

along with speech, writing, and warfare - is among the most elemental and universal expressions of humanity.

But what are we to do when providing or accepting hospitality - be it a meal or a place to stay for the night - is equally

fraught with ethical and pragmatic pitfalls? How do we reconcile the facts that we are incomplete alone and compromised in

company? This is not, of course, a question limited to the manifestations of hospitality, but hospitality is an ideal medium

for cultivating its nuances. The history of hospitality records its protagonists, from Gertrude Stein to the Emperor Nero,

from Alaric the Goth to John James Audubon, at the moment when they come face to face with this paradox, unwittingly or by

design. Each acquits himself or herself with varying degrees of ingenuity and self-deception, but none comes any closer than

I have to resolving it. The best we can do, probably, is to return to Epicurus.

Epicurus reminds us that "the end of all our actions is to be free from pain and fear." Whatever we may do, he says including

giving pleasure to others - we ultimately do to please ourselves, and even friendship is only the most important of those

means "which wisdom acquires to ensure happiness throughout the whole of life." This is not about selfishness; it is the realistic

and necessary starting point of a journey on which we must seek to divest ourselves of the unnatural desires that make us

unhappy. If we are lucky or persistent enough to achieve an understanding of desires whose pursuit brings us nothing but frustration,

bitterness, and self-doubt, we can perhaps hope to eliminate them. The philosophy of Epicurus is not about achieving happiness

through self-indulgence, as many imagine; it is about recognizing that almost all the pain and fear of our lives are based

on seeking that which is not good for us. Happiness comes neither by gratifying nor by denying our desires, but by excising

them. We are all doomed to seek our own happiness; we can't help ourselves. We are all, the cruel and the gentle alike, condemned

to seeking that happiness in the dark. We use our need as the blind use a walking stick, to determine the safety of every

forward step. We must seek instead to know what we really want and why we want it - and stop fooling ourselves that things

are good merely because we desire them.

The history of hospitality is the battlefield in which this timeless struggle with our own nature is played out in all its

bloody dishonesty. It is here that we are confronted with the unspeakable truth, as inevitable as the process of natural selection

and evolutionary adaptation that produced us, that we communicate with each other exclusively in a language of mutual benefits.

It is here that generosity meets the pleasure principle. It is here that auditors shield themselves from their own concupiscence.

It is here that refined Southern gentlemen restrain themselves from slaughtering each other. It is here that we come to understand,

clearly and without flinching, Abraham's message that self-interest is the chariot of salvation. Hospitality, we'll see, is

rarely about giving the guest what she needs; it is all about, and always has been about, giving the host what he needs. It

is a sleight of hand whereby the host attempts to persuade the guest that she has been gratified while he reaps the far greater

profit himself. Whether that profit is emotional, political, financial, or sexual is irrelevant. What is important is that

hospitality be seen not as a gift, but as the transaction that it is, a trade-off so subliminal even the host may not be aware

it has taken place, or of the ways in which it has profited him.

Since common wisdom generally ranks hospitality among the cardinal virtues - right alongside charity, mercy, self-sacrifice,

loyalty, and temperance - this is a lesson that most of us will tend to resist and that cannot be learned frivolously. That

is why I have chosen to deliver it in reverse chronological order in this book, easing us backward through time as a sleeper

gradually descends into the realm of dreams, where demons that ought not be approached too abruptly may await. It is also

why I have deliberately limited my scope of inquiry to Western civilization: just as I have never learned anything of much

interest in my dreams about anyone other than myself, so too I deemed it wise to stick to what I have at least a chance at

understanding.

I labored under years of self-deception to recognize and acknowledge the subversive power of my poker sandwiches; before that,

I had myself convinced that I was merely giving my guests a decent meal and that simple thanks were my only due reward. I

can't say that I'm a better person for this self-knowledge, but at least I have laid bare the moral dilemma underlying my

actions. Either I maintain my culinary standards and count my winnings, or I serve up Blimpies and lose my shirt.