The Egypt Code (5 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

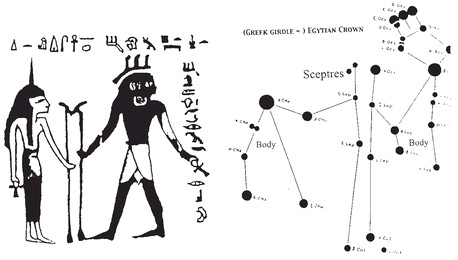

Representation of Sirius and Orion during the Middle Kingdom

In 1912 the German archaeologist Hermann Junker, while excavating south of the Sphinx’s Causeway at Giza, discovered a

serdab

attached to a

mastaba

belonging to a Fifth Dynasty official called Rawer. Most fortuitously the

serdab

had inscriptions on it. Judging from the important location and also the size of the

mastaba

, Junker concluded that Rawer had been a very important official and even perhaps a member of the royal family. Although Rawer’s

serdab

did not have rounded peepholes, it did have a long squint cut in the north face that had probably served the same purpose. Indeed, according to British Egyptologist A. M. Blackman, who studied Rawer’s

serdab

, the squint symbolised the ‘eyes’ of the

serdab

. And most revealing, above the ‘eyes’ were inscribed the words

house of the ka

.

14

serdab

attached to a

mastaba

belonging to a Fifth Dynasty official called Rawer. Most fortuitously the

serdab

had inscriptions on it. Judging from the important location and also the size of the

mastaba

, Junker concluded that Rawer had been a very important official and even perhaps a member of the royal family. Although Rawer’s

serdab

did not have rounded peepholes, it did have a long squint cut in the north face that had probably served the same purpose. Indeed, according to British Egyptologist A. M. Blackman, who studied Rawer’s

serdab

, the squint symbolised the ‘eyes’ of the

serdab

. And most revealing, above the ‘eyes’ were inscribed the words

house of the ka

.

14

The Egyptians believed that a human being was made of various unseen entities, in much the same way as we think of a person having a spirit, a soul, an ego and so on. An important entity was the

ka

, which is generally defined by Egyptologists as the ‘double’ or ‘essence’ of a person, a sort of alter ego that was an integral part of that person’s life and, after death, his afterlife. Another important entity was the

ba

, generally defined as the ‘soul’ of the person, which was imagined to become a star after the person’s death. We shall return to the

ba

and its relation to stars later on. Meanwhile, a more elaborate and even more revealing definition of the

ka

is given by the Egyptologist Manchip-White:

ka

, which is generally defined by Egyptologists as the ‘double’ or ‘essence’ of a person, a sort of alter ego that was an integral part of that person’s life and, after death, his afterlife. Another important entity was the

ba

, generally defined as the ‘soul’ of the person, which was imagined to become a star after the person’s death. We shall return to the

ba

and its relation to stars later on. Meanwhile, a more elaborate and even more revealing definition of the

ka

is given by the Egyptologist Manchip-White:

the

Ka

was born with a person and remained earthbound on his death. At the instant of death a man’s

Ka

and his body were united. The

Ka

lived in the tomb with the mummy, feeding upon the daily offerings and

dwelling in the statue

enclosed in the serdab

15

. . . The idea that the

Ka

‘dwelled’ in the statue of the dead person is made evident in this passage from the ancient funerary texts, where the dead person declares: ‘

Let my Ka be remembered after my life; let my statue abide and my name endure . . .

’

16

The

ka

statue in the

serdab

also had to be nurtured in the same manner the person it belonged to had been nurtured during his lifetime. Food offerings to the statue were, of course, symbolic and were depicted in drawings on the walls of the tomb, although real food was often part of the funerary items. On such drawings the most prominent depiction was the thigh of a bull or calf. The thigh - or rather its plough-like shape, as we shall see later - was called

meskhetiu

. The

meskhetiu

was generally carried by a priest, who solemnly presented it to the

ka

of the deceased. Curiously, the same word,

meskhetiu,

described a small metal cutting tool, a sort of carpenter’s adze, used on the mummy in a ceremony known as ‘the opening of the mouth’. In this ceremony the mouth of the mummy was symbolically sliced open with the cutting tool to allow the ‘breath of life’ to enter the corpse of the deceased. The word

meskhetiu

, oddly enough, was used also to describe a constellation of stars which today we call the Plough (or the Big Dipper in the US). It was often drawn on the ceilings of tombs and on the lids of sarcophagi in the form of a bull’s thigh sometimes surrounded by seven stars. The common denominator between these three types of

meskhetiu

- the bull’s thigh, the carpenter’s adze and the Plough - was clearly their adze- or plough-like shapes. From my astronomy I knew that the Plough constellation had always been seen in the northern sky (it still is today), and that once a day it would have passed into the line of sight of the

ka

statue in the

serdab

.

ka

statue in the

serdab

also had to be nurtured in the same manner the person it belonged to had been nurtured during his lifetime. Food offerings to the statue were, of course, symbolic and were depicted in drawings on the walls of the tomb, although real food was often part of the funerary items. On such drawings the most prominent depiction was the thigh of a bull or calf. The thigh - or rather its plough-like shape, as we shall see later - was called

meskhetiu

. The

meskhetiu

was generally carried by a priest, who solemnly presented it to the

ka

of the deceased. Curiously, the same word,

meskhetiu,

described a small metal cutting tool, a sort of carpenter’s adze, used on the mummy in a ceremony known as ‘the opening of the mouth’. In this ceremony the mouth of the mummy was symbolically sliced open with the cutting tool to allow the ‘breath of life’ to enter the corpse of the deceased. The word

meskhetiu

, oddly enough, was used also to describe a constellation of stars which today we call the Plough (or the Big Dipper in the US). It was often drawn on the ceilings of tombs and on the lids of sarcophagi in the form of a bull’s thigh sometimes surrounded by seven stars. The common denominator between these three types of

meskhetiu

- the bull’s thigh, the carpenter’s adze and the Plough - was clearly their adze- or plough-like shapes. From my astronomy I knew that the Plough constellation had always been seen in the northern sky (it still is today), and that once a day it would have passed into the line of sight of the

ka

statue in the

serdab

.

Scanning through the Pyramid Texts

-

those sacred writings that were found engraved on the walls of Fifth and Sixth Dynasty royal pyramids at Saqqara

17

- I found a particular passage that gave a rather vivid picture of the dead king sharing his pyramid with his

ka

. What grabbed my attention, however, was the curious way the pyramid had been described: ‘A boon . . . that this pyramid and temple be installed for me and my

ka

. . . Anyone who shall lay a finger on this pyramid and this temple which belong to me and my

ka

, he will have laid his finger on the Mansion of Horus in the sky . . .’

18

The enigmatic description of ‘the Mansion of Horus in the sky’ given to the pyramid had, as one can imagine, a familiar ring to it. It was, of course, uncannily similar to the name given to the Step Pyramid’ ‘Horus is the Star at the Head of the Sky’. It was obvious that both these names strongly indicated that the pyramids were imagined to have their counterparts in the sky in the form of stars. Or, to put it inversely, that certain stars (in this case one associated with Horus) were symbolised on the ground by certain pyramids. As early as 1977 the Egyptologist Alexander Badawy had drawn attention to precisely this pyramids- stars connection when he wrote that ‘the names of the Pyramids of Snefreru, Khufu, Dededfret, Nebre indicate clearly stellar connotations while those of Sahure, Neferirkare and Neferefre describe the stellar destiny of the Ba (soul).’

19

-

those sacred writings that were found engraved on the walls of Fifth and Sixth Dynasty royal pyramids at Saqqara

17

- I found a particular passage that gave a rather vivid picture of the dead king sharing his pyramid with his

ka

. What grabbed my attention, however, was the curious way the pyramid had been described: ‘A boon . . . that this pyramid and temple be installed for me and my

ka

. . . Anyone who shall lay a finger on this pyramid and this temple which belong to me and my

ka

, he will have laid his finger on the Mansion of Horus in the sky . . .’

18

The enigmatic description of ‘the Mansion of Horus in the sky’ given to the pyramid had, as one can imagine, a familiar ring to it. It was, of course, uncannily similar to the name given to the Step Pyramid’ ‘Horus is the Star at the Head of the Sky’. It was obvious that both these names strongly indicated that the pyramids were imagined to have their counterparts in the sky in the form of stars. Or, to put it inversely, that certain stars (in this case one associated with Horus) were symbolised on the ground by certain pyramids. As early as 1977 the Egyptologist Alexander Badawy had drawn attention to precisely this pyramids- stars connection when he wrote that ‘the names of the Pyramids of Snefreru, Khufu, Dededfret, Nebre indicate clearly stellar connotations while those of Sahure, Neferirkare and Neferefre describe the stellar destiny of the Ba (soul).’

19

Later, in 1981, the distinguished British Egyptologist I.E.S. Edwards looked into this mysterious correlation between stars and pyramids and pointed out that the names of two pyramids belonging to the Fourth Dynasty kings Djedefra and Nebka, ‘Djedefra is a

sehed

star’ and ‘Nebka is a star’, ‘clearly associate their owner with an astral after-life.’

20

And more recently the Egyptologist Stephen Quirke brought this matter up again by noting that, ‘The (names of the) Step Pyramid of

Netjerkhet

(Djoser) and the Abu Ruwash complex of Djedefra are explicitly stellar, in the one case using the word

seba

“star”, in the other case using the word

sehdu

“firmament” or “starry sky”. By contrast, there is not a single instance where the name of a pyramid refers explicitly to the sun.’

21

sehed

star’ and ‘Nebka is a star’, ‘clearly associate their owner with an astral after-life.’

20

And more recently the Egyptologist Stephen Quirke brought this matter up again by noting that, ‘The (names of the) Step Pyramid of

Netjerkhet

(Djoser) and the Abu Ruwash complex of Djedefra are explicitly stellar, in the one case using the word

seba

“star”, in the other case using the word

sehdu

“firmament” or “starry sky”. By contrast, there is not a single instance where the name of a pyramid refers explicitly to the sun.’

21

These ‘explicitly stellar’ names given to pyramids carry a clear and straightforward message: pyramids on the ground are to be regarded as ‘stars’. If this was true, then the implications were astounding, and a whole new rethink of what motivated the ancient Egyptians to build pyramids was required. This was precisely what I had done, starting in 1983, at the Giza pyramids. I knew that now I was about to do the same again for the Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara. For I very much suspected that the ‘star’ that the Step Pyramid represented on earth was no ordinary star, but one that was deemed vital to the welfare of Egypt; a star, no less, that was imagined to completely control, as the Hermetic texts said, ‘all things on earth’.

The Plough is not, strictly speaking, a constellation. Some astronomers will insist on calling it an asterism because its seven bright stars are part of the larger constellation we call the Great Bear or Ursa Major. But to any casual observer it is only those seven stars and not the whole of the Great Bear constellation which stand out, with their distinct pattern of a plough or dipper. This often causes many people to erroneously use the name Great Bear when they in fact really mean Plough. This, most annoyingly, is especially true of Egyptologists, which has caused much confusion all round. At any rate the ancient Egyptians, like most people, perceived only the pattern of the seven bright stars, which they likened not to a plough but to a bull’s thigh. This is the constellation they called

meskhetiu

, and it figured prominently in their religious texts and funerary drawings in connection with the afterlife destiny of kings and nobles. It was one of three distinct constellations, along with Ursa Minor (the Little Bear) and Draconis (the Dragon), that, in ancient times, revolved perpetually around the north pole of the sky like a wheel. The stars in these constellations were known as the

ikhemu-set

, which means ‘the Imperishable Ones’ or ‘the Indestructible Ones,’

22

and are known to modern astronomers as the circumpolar stars because they perpetually circumnavigate the north celestial pole, making them the perfect metaphor for ‘eternal life’, due to the fact that they never set but are always visible in the night sky. As early as 1912 the influential American Egyptologist James H. Breasted was to write that, ‘it is especially those (stars) which are called “the Imperishable Ones” in which the Egyptians saw the host of the dead. These are said to be in the north of the sky, and the suggestion that the circumpolar stars, which never set or disappear, are the ones which are meant is a very probable one.’

23

meskhetiu

, and it figured prominently in their religious texts and funerary drawings in connection with the afterlife destiny of kings and nobles. It was one of three distinct constellations, along with Ursa Minor (the Little Bear) and Draconis (the Dragon), that, in ancient times, revolved perpetually around the north pole of the sky like a wheel. The stars in these constellations were known as the

ikhemu-set

, which means ‘the Imperishable Ones’ or ‘the Indestructible Ones,’

22

and are known to modern astronomers as the circumpolar stars because they perpetually circumnavigate the north celestial pole, making them the perfect metaphor for ‘eternal life’, due to the fact that they never set but are always visible in the night sky. As early as 1912 the influential American Egyptologist James H. Breasted was to write that, ‘it is especially those (stars) which are called “the Imperishable Ones” in which the Egyptians saw the host of the dead. These are said to be in the north of the sky, and the suggestion that the circumpolar stars, which never set or disappear, are the ones which are meant is a very probable one.’

23

Today Breasted’s views are universally accepted. Indeed, the British Egyptologist R.T. Rundle Clark drove the same point even further by asserting that ‘no other ancient people were so deeply affected by the eternal circuit of the stars around a point in the northern sky. Here must be the node of the universe, the centre of regulation.’

24

In the same vein, the archaeoastronomer E.C. Krupp, an accredited specialist in this field, also pointed out that the Egyptians associated the Plough ‘with eternal life because its stars are circumpolar. They were the undying, imperishable stars. In death the king ascended to their circumpolar realm, and there he preserved the cosmic order.’

25

The idea that the king preserved the ‘cosmic order’ or harmony of the universe by making use of the circumpolar stars as ‘the centre of regulation’ is most intriguing, because it may indeed explain the cosmic function of the

ka

statue in the

serdab

and why its gaze is eternally locked on these stars. Actually, the cosmic order that Krupp was alluding to was called Maat by the ancient Egyptians. Maat was their most fundamental and important religious tenet, and was portrayed as a seated goddess wearing an ostrich feather - the ‘feather of truth’ - on her head. The pharaohs were often shown presenting a small figure of Maat to the gods, the supreme gesture of piety and respect, and they often adopted the epithet ‘Beloved of Maat’. The goddess Maat figured prominently in the so-called Judgement Scene where the souls of the dead were weighed against the feather of truth. Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the whole religious edifice upon which the pharaonic theocracy rested was Maat.

24

In the same vein, the archaeoastronomer E.C. Krupp, an accredited specialist in this field, also pointed out that the Egyptians associated the Plough ‘with eternal life because its stars are circumpolar. They were the undying, imperishable stars. In death the king ascended to their circumpolar realm, and there he preserved the cosmic order.’

25

The idea that the king preserved the ‘cosmic order’ or harmony of the universe by making use of the circumpolar stars as ‘the centre of regulation’ is most intriguing, because it may indeed explain the cosmic function of the

ka

statue in the

serdab

and why its gaze is eternally locked on these stars. Actually, the cosmic order that Krupp was alluding to was called Maat by the ancient Egyptians. Maat was their most fundamental and important religious tenet, and was portrayed as a seated goddess wearing an ostrich feather - the ‘feather of truth’ - on her head. The pharaohs were often shown presenting a small figure of Maat to the gods, the supreme gesture of piety and respect, and they often adopted the epithet ‘Beloved of Maat’. The goddess Maat figured prominently in the so-called Judgement Scene where the souls of the dead were weighed against the feather of truth. Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the whole religious edifice upon which the pharaonic theocracy rested was Maat.

Although Egyptologists generally define it as ‘truth, justice and balance’, a closer examination shows that Maat was also intrinsically linked to the harmony and order of the cosmos, which principally entailed the stately motion of stars and their relation to the cycle of nature. As Egyptologists Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson further explain:

On a cosmic scale, Maat also represented the divine order of the universe as originally brought into being at the moment of Creation. It was the power of Maat that was believed to regulate the seasons, the movement of the stars and the relation between men and god. The concept was therefore central both to the Egyptians’ ideas about the universe and to their code of ethics.

26Kingship belonged much more with the overall role of the king in imposing order and preventing chaos. The function of the king as the representative of the gods was to preserve the original harmony of the universe, therefore a great deal of the iconography in Egyptian temples, tombs and palaces was concerned much more with this overall aim than with the individual circumstances of the ruler at any particular point in time.

27

From these definitions it is self-evident that the Egyptians believed in a heavenly force or power that regulated the movements of the constellations in the sky and the changing of the seasons on earth, and that somehow the king could control this power. Attached to this belief was also the notion that there had been a time when sky and earth were one and in perfect harmony. In the so-called Heliopolitan creation myth, the sky-goddess Nut and the earth-god Geb were at first locked in a tight embrace and the fruit of their amorous union were the twin souls and archetypal lovers Osiris and Isis, who became the first divine king and queen of Egypt and bore the first Horus-king. But then Nut ‘swallowed’ her children to make them ‘stars’ in her body. Because of this act of infanticide she suffered the eternal punishment of being separated from her husband by the hand of her father Shu, the air-god.

28

But now sky and earth were out of synch. No more did the cycle of the stars in the sky perfectly match that of nature on earth. For the Egyptians, whose very survival relied entirely on the regularity of the Nile’s flood, this presented a serious problem. As we shall see in the next chapter, the annual flood had to be predictable and ‘good’, otherwise calamity befell the land and its people. And so from this constant fear was spawned the belief that the cosmic order of the sky, which was perfect and could be relied on to the nearest minute, could be brought down to earth through the magical power of rituals. Only by the stringent adherence to Maat could the pharaoh ensure the welfare of Egypt and the regulated and orderly flooding of the Nile.

28

But now sky and earth were out of synch. No more did the cycle of the stars in the sky perfectly match that of nature on earth. For the Egyptians, whose very survival relied entirely on the regularity of the Nile’s flood, this presented a serious problem. As we shall see in the next chapter, the annual flood had to be predictable and ‘good’, otherwise calamity befell the land and its people. And so from this constant fear was spawned the belief that the cosmic order of the sky, which was perfect and could be relied on to the nearest minute, could be brought down to earth through the magical power of rituals. Only by the stringent adherence to Maat could the pharaoh ensure the welfare of Egypt and the regulated and orderly flooding of the Nile.

Other books

A Good-Looking Corpse by Jeff Klima

An Owl Too Many by Charlotte MacLeod

Moonlight and Shadows by Janzen, Tara

Stepbrother With Benefits 17 (Third Season) by Mia Clark

The Myriad Resistance by John D. Mimms

Misterio del príncipe desaparecido by Enid Blyton

The Headmaster's Wife by Greene, Thomas Christopher

Killer by Sara Shepard

Chase the Wind by Cindy Holby - Wind 01 - Chase the Wind

Chasing Xaris by Samantha Bennett