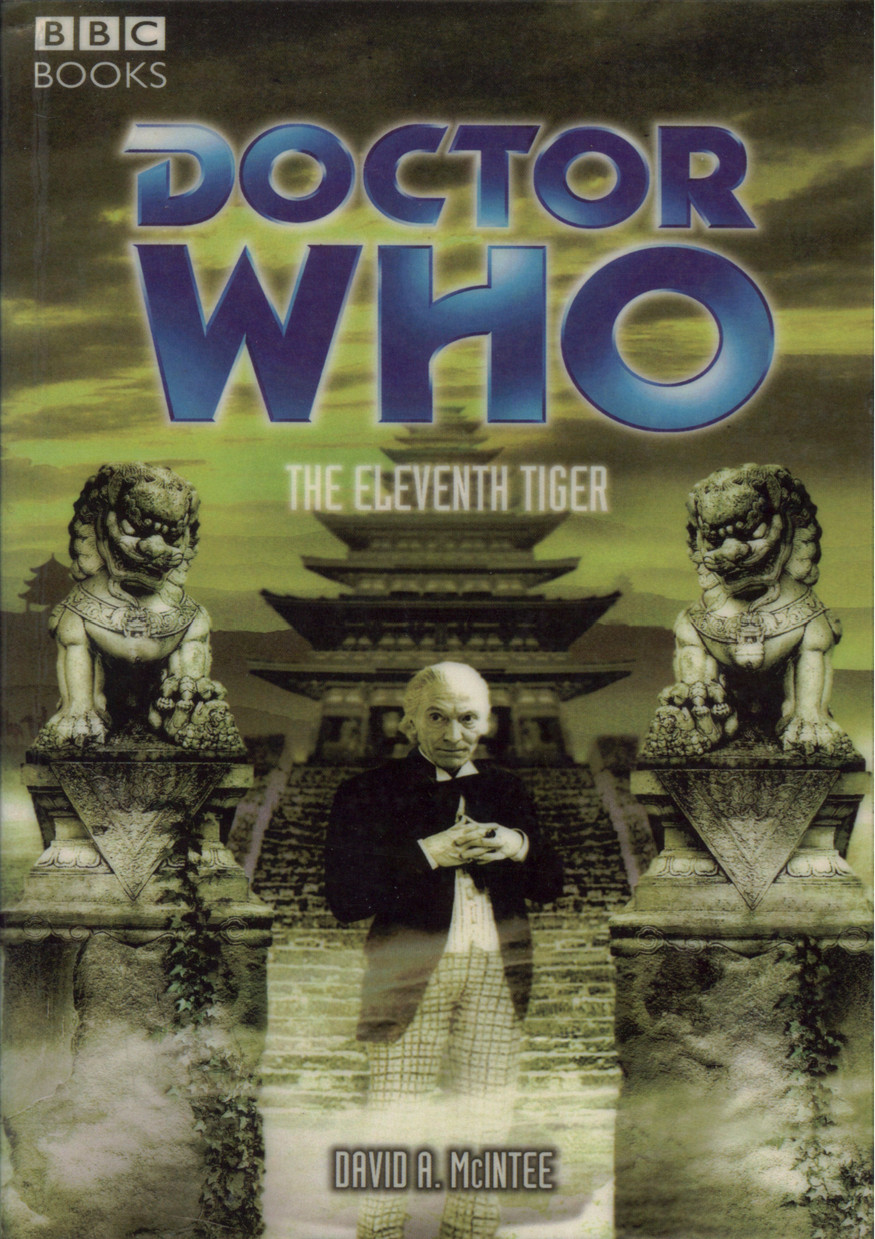

The Eleventh Tiger

THE ELEVENTH TIGER

DAVID A. MCINTEE

B B C

Published by BBC Worldwide Ltd,

Woodlands, 80 Wood Lane

London W12 OTT

First published 2004

Copyright © David A. McIntee 2004

The moral right of the author has been asserted Original series broadcast on the BBC

Format © BBC 1963

Doctor Who and TARDIS are trademarks of the BBC

ISBN 0 563 48614 7

Imaging by Black Sheep, copyright © BBC 1999

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham Cover printed by Belmont Press Ltd, Northampton

If this book is dedicated to anybody,

it should be to Gary and Linda Stratmann,

and to Derek Arundale and the rest of the folks in

Yorkshire’s Ji-Tae school of Taekwondo.

‘Beauty and anguish walking hand in hand The downward

slope to death’

- The Dream of the Red Chamber

CUTAWAY I

Translated in 1890, from the surviving fragment of ‘Mountains

and Sunsets’ by Ho Lin Chung (AD 1537):

One thousand seven hundred and forty-seven years ago, a Taoist priest, who happened to be passing a hill, sat down for a while to rest under a tree. As the priest ate some bread and rice, he noticed a disconsolate piece of jade which also lay in the shade of his tree.

This piece of jade was in the fashion of a delicate bracelet, of a kind the priest’s sister liked to wear. His curiosity aroused by this, he picked up the jade, and was astonished when it began to speak to him.

‘Sir Priest,’ the stone said, ‘perhaps a tale will help your meal settle, and pass the cold night more agreeably.’ The priest agreed, and the jade told him the story which was inscribed upon it.

So moved was the priest by the jade’s tale, he copied it out from beginning to end as the stone told it to him. Here it is: Under a Dynasty which the jade leaves unnamed, two Generals had greatly distinguished themselves in battle.

These Generals were brothers, by the names of Zhao and Gao, and they were the favourites of the Emperor and lived with him in his great palace at Chang’an. They are the heroes of this tale.

These men, these brothers, divided between them the virtues of a warrior. Zhao was stronger than two oxen, heavy of feature, and a more powerful man the Emperor had never seen. Gao was fleet of foot, and with the agility of any monkey, but his features were fine and well turned.

One day, the Emperor bade his Generals bring to him the most learned priests and scholars in the Empire. Gao ran the length and breadth of the Empire, taking the Emperor’s orders to every school and temple in every city of the Seven Kingdoms. In this way, one thousand six hundred and forty priests and scholars were prepared when Zhao arrived to carry them all to the Emperor’s palace.

‘Great Majesty,’ the Generals said, ‘here are the priests and scholars you bade us bring to you.’

The Emperor remained as aloof and regal as befits Heaven’s representative on Earth. He retreated with the priests and scholars, and for ten years the Emperor was not seen, not even by his two favourite Generals.

During these long years, made sad by the absence of their beloved Emperor, the brothers took good care of the Empire.

They also loved and married, and became fathers to strong sons, whose descendants would be Generals for ever more.

After those ten long years, the Emperor once again called the brothers to his side. ‘Loyal Generals,’ the Emperor said,

‘you have done well to do my bidding while I have been studying with these priests and scholars. Now I have a task for you.’

‘Anything, Great Majesty,’ the Generals replied. The Emperor smiled, pleased by their loyalty and their prowess at doing his will. The Emperor pointed to the one thousand six hundred and forty men of learning, and told his Generals to put them all to the sword, that no-one else might learn from them what he had learnt.

Being warriors, the work of dispatching men by the sword was familiar and easy to the brothers. Gao slashed more quickly than the eye could see, piercing ten in the time it takes a man to blink. His brother Zhao clove men in two with the tiniest gesture of his great sword.

Overcome with emotion, the Generals thanked the Emperor, and begged him to give them new orders that they might obey to please him further. ‘Test your soldiers,’ the Emperor ordered, ‘and choose the eight thousand best among them to be brought before me.’

This the brothers did, and soon the eight thousand greatest warriors in the Emperor’s army paraded before him. The Emperor was pleased. ‘You will come with me,’ he said, ‘into Heaven and Hell. You will be my bodyguards for ever.’

Having so engaged these men, the Emperor sought to have them prove themselves to him, and so he instructed them to take every scroll and book and map from every library in the Empire. When the Eight Thousand had gathered this proud and eclectic population, the Emperor had the frightened books built into the shape of a hill. ‘Now,’ he told the books,

‘your secrets will remain secret, and I will guard them well, and you will never tell.’

So saying, the Emperor had his beloved Generals join the brightness of flame to the dryness of the paper, that none of the garrulous books could divulge secrets that only the Emperor should know. Only one brave scroll remained: a map, which was the Emperor’s closest companion and dearest friend.

Led by the map, the Emperor took the Generals and the Eight Thousand to the Islands of Japan. There, under his leadership, and the brothers’ skills at warfare, the warriors triumphed over all who stood against them. The loyal map had brought its Emperor safely to the castle of a great Shogun, who was also a priest. It was this man whom the Emperor wished to speak with.

The Shogun-priest’s castle was built upon a mound of stones two hundred and twelve feet high, and guarded by one hundred thousand samurai. The Emperor’s eight thousand warriors were each worth twenty samurai, and quickly turned the tide of battle. The samurai were cut down easily by the best warriors in Asia.

The Shogun-priest laughed at this, for the samurai’s duty was to die for his master. Impressed by the Emperor and the Eight Thousand, the Shogun held a great feast to celebrate that they had passed the test he set them.

The Shogun then gave the Emperor a great gift, telling the Emperor all that he needed to know to fulfil his dreams. He also taught the Emperor to read the stars in the sky, to know when Heaven was closest to the Earth, and most reachable.

The Shogun then left his castle.

When the Generals came to him once more, the Emperor rewarded them with amulets given to him by the Shogun-priest. Zhao received a most marvellous piece of jade, with the inscription: ‘Lose me not, forget me not, Eternal life shall be your lot.’ Gao was awarded a wonderful gold amulet, upon which also were certain words inscribed. On it was written:

‘Let not this token wander from your side, And youth peren-nial shall with you abide.’

Watching the stars as the Shogun-priest had taught him, the Emperor decided that it was time that he, his Generals, and the eight thousand best warriors in the world, took their place in Heaven. And so, the Emperor entered Heaven upon his return from the Islands of Japan.

His son, and the brothers who were Generals, followed the instructions that the Emperor had given to them, and which he had received from the one thousand six hundred and forty priests and scholars.

And the Generals, loyal and fearless as warriors should be, followed their Emperor in all things, and with strength and quickness of fist, foot and sword, conquered Heaven and Hell. All but one.

And there the Taoist priest stopped writing, with the rising of the sun. The cold night had indeed passed agreeably. But the priest’s curiosity was not sated, and he asked the jade:

‘What of the one you mentioned? What of his tale?’

‘If you return this way another night,’ the jade told him, that tale will pass that night as agreeably as this one, for it is another story.’

Executioners from Shaolin

l

Hoof beats and heartbeats blended into a frantic drumming in Cheng’s ears. His horse wasn’t foaming at the mouth yet, but he could tell it was only a matter of time - and not a long time, at that.

The Mongols used to say that a fast horse under you, and the wind in your hair, were among the best things in life.

Maybe that was true if you rode simply for pleasure. As he rode in flight Cheng thought the cold air stinging his eyes, and the bouncing of the horse’s strong back hammering at his spine, were the least pleasant necessities he knew of.

A glance over his shoulder showed that his companions were keeping up with him, the faces of their mounts contorted in wild effort. Like himself, the men all wore loose shirts and dark trousers. Also like himself, they were all festooned with daggers, swords and bows. Beyond them there was no sign of the expected pursuit.

Cheng slowed his horse. His companions followed suit as they came alongside. ‘You think we’ve put enough distance between us and that caravan?’ Li asked, wiping the dust from his scarred face.

‘Yes,’ Cheng said. ‘I see no horses following us. Anyway, ours need to rest before they drop dead under us.’ He looked up at a leaden sky that was darkening by the moment. ‘We’ll need to find shelter, and soon.’

Li looked up and nodded. ‘Bad one coming.’

‘As bad as I’ve seen,’ Cheng agreed.

He looked round at his group. Nine men, including himself, and nine horses. They would need more than a woodsman’s hut to shelter in. A full-sized farm would be best, but there was nothing of that nature in sight.

Fields stretched for miles, with only the occasional patch of bushes to offer any kind of cover. To the left a hill rose, its sides scattered with trees.