The End of Sparta (11 page)

Authors: Victor Davis Hanson

Far too late, Kleombrotos and Lichas ordered Sphodrias and his folk at the tip of the spears to get the men moving to the far right, to bypass this onrushing mob so much deeper than anything they had ever fought. Mêlon was now right in front of the king’s line. Yes, he was to face Lichas once more, perhaps as Malgis had. But now Mêlon took heart that once more Lichas would bear out a Spartan king on his back, perhaps this time dead rather than wounded. He pressed on; yes, this time Lichas would carry out a dead king.

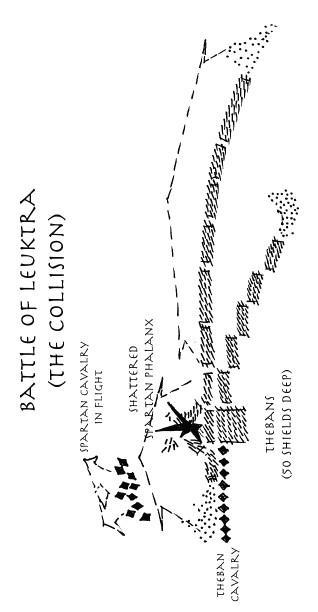

Mêlon could feel that gaping holes were opening, as yet more pockets of Theban rustics surged in. Too few Spartans stepped up to plug the gaps made by such spearmen. Mêlon and Chiôn, with Staphis and Antitheos and his men to the left, were already, at this very beginning of battle, three or four ranks beyond the Spartan front line. They were almost as far into the enemy phalanx as Pelopidas and the Sacred Band fifty or so feet farther to their left on the wing. Over there out of sight, the Sacred Band had avoided the crash. Instead they had already trotted around the Spartan line, and well past the king. From the side and now from the rear, the Sacred Band began to encircle the Spartan horn. Pelopidas’s men were herding the enemy back into the spears of the advancing left under Epaminondas, Mêlon, and Chiôn. Already the Spartans were nearly surrounded, their entire right flank blocked at every side. Mêlon’s Thebans were like Helikon goat dogs, nipping the ankles of the rams, herding them together as they were forced into the pen. The Spartans were in danger not of losing, but of being destroyed to a man.

Across the way, Lichas saw the disaster. Almost alone he felt this doom of his royal right. He pointed to the king’s guard to keep to the right. “Break out of the pig jaws. Trot out. We break out of their ring, quick time, now. March on the double-step. Listen to our pipers.”

As the Spartans tried to spear a way out of the closing circle, Staphis, Chiôn, and Mêlon held firm. The three were drifting more and more to the left as planned, batting down spear thrusts, jabbing Spartans as they worked their way onward toward the royal guard itself. More Spartan bodies lay at their feet as they stepped ahead—twitching like the fishermen’s speared tunny, but trapped in their scales of armor. Staphis crushed a prone man’s throat with his hobnailed sandal. Those coming up behind with their still-raised spears finished him off, slamming their butt-spikes straight down through his eye-slits, once the Spartan’s shield was splintered and then hammered down flat. For these in the rear who would not meet the first storm of the Spartan, their grand tales back home at the pottery stalls would be of pushing their friends ahead and smashing their spear-butts, their

saurôtêres

, into hundreds of Spartans that they trampled and stepped on. Soon the Thebans, as song would have it in the years to follow, were walking over the dreaded schoolmasters of war—Spartans cast down like mere scraps of meat on the dirty floor of the raucous banquet hall.

Just then Mêlon felt a surge of warm power in his arms, a flow, a

rheuma

of heat. It came without warning over him. As he moved more freely, his muscles became fluid, no longer stiff, his leg limber, his knee no longer fused, his back loose. I am now an ephebe, he thought, younger even than at Koroneia some twenty-three seasons ago, more like at Haliartos when I was a down-beard. Just as if Mêlon had left the tall trees over the gloomy pass of Mt. Kithairon and reentered on the downward hike the sunlight of the rolling foothills, so he pressed on as fewer spears glanced off his wood and bronze. The battlefield had changed yet again. He now had far more space to swing wide his arms. Above Helios had long ago come out; the clouds of gloom were gone. He could hear and see far better now. For all the dust and noise, his senses sharpened with each step ahead as he saw fewer shapes and shadows. His shield felt as if the willow was instead oak, his breastplate more like iron than thin bronze, his helmet impenetrable to a jab from Zeus himself.

Everything was clear. This was the

aristeia

, the surge of victory and power that Homer sung of Achilles in battle. Now it was infused in him. He was light on his feet, his arms were supple and hot—and he would win this day. No more Chôlopous. No, he was Ôkupous. Lord of the fast feet. Like swift-footed Achilles of old. Then Mêlon felt that the grip on his shield was not quite right, that the straps and clasp, the

porpax

and

antilabê

, had been torn and bent and were out of balance. His shield string had long ago snapped. From the corner of his left eye he saw the problem: a Spartan spearhead and two fingers’ worth of the wood of its broken socket still stuck into his boss. How forceful the collision a moment earlier had been with the front line of the enemy.

But even his shield mattered less now. The willow of all the Thebans of the front line rattled less frequently as fewer blows bounced off their

aspides

, following the grand

pararhexis

of the enemy front. Soon the lines would open up even more as the Thebans’ push sent his own men on through the Spartans. Now the hoplites at his rear would have their own room to swing their shields and stab down over the enemy’s shield rims. Mêlon was ready to go for his sword on his shoulder, since even his father’s spear Bora was cracked. But for now it was enough to keep heading left. Always lean, Mêlon remembered, lean left. Cover little Staphis with the shield. Cover him. He lives yet.

Mêlon knew that from the feel of the man at his side. Staphis had matched his own step. This farmer of grapes could yet make it through the din, if there were no longer a solid line of Spartan spears ahead. With Chiôn always a pace ahead, and Staphis on the left one to the rear, their small bulge in the line went ahead at a sort of diagonal—just as Ainias had foreseen for the entire Theban left.

As in any great enterprise, the surge of passion comes not from the enjoyment of the success, but mostly in the immediate anticipation. There are only a few moments in this life when a man can gauge that all good things are just about to happen to him. Not even the gods can stop what surely is fated. The Spartans, Mêlon felt, were being obliterated. They were all stumbling, falling, turning. He let out another yell. How could he have stayed back on Helikon while the men of Boiotia bled on the ground of his Leuktra? For the next ten summers he would not have sat in the shadows of the wheelwright, with head down at the smithy, only to hear other, lesser men boast of their kills here at White Creek. Mêlon clobbered another bare neck of a falling Spartan with his shield rim and kicked at two squirming at his feet. How good he was at the work of war and how easily in a mood like this he would kill any men in his way.

No, he liked this leftward plunge, as the new Theban army pushed him ever on toward a collision with the Spartan king. “Stay with me, Staphi, stay close with your fast foot, my

taxupous

.” As the Spartans gave way, still more Thebans surged from the rear, left their files, crowding forward in the blood lust for killing. Just then Mêlon felt iron from the rear tear his forearm. The same fool Theban behind him—Aristaios he thought this olive-crusher was—a moment later hit the back of Mêlon’s helmet with his shield. But Aristaios’s hot breath on his neck ended when a long Spartan thrust went over his right shoulder and into the tall Theban’s throat. That was about all Mêlon could tell. A taller Spartan, one of these guardsmen of the king perhaps—Mêlon would later learn his name was Klearchos, son of the famous drill-master who recruited the Ten Thousand—jabbed his spear right toward Mêlon’s jaw. The Spartan aimed to hit somewhere between his nose guard and the upper rim of his shield. Mêlon ducked well in time from the clumsy effort. Then he rose to bash at the man’s face with his shield rim.

Klearchos was knocked to the side into Staphis. The slight rustic held firm. With a jab of his spear shaft he hit the falling Spartan in the back of the neck as he strove to keep pace with Mêlon. Staphis knew more than just how to prune the choice canes of his winter vines. For the first time he had hit living flesh, and so robbed the strength from a Spartan peer no less. Is it ever an easy thing to kill the better man? Staphis in his greenness speared too deeply. Now, if just for a moment, his point stuck on the enemy’s backplate near the rim by the neck, and threw him off balance. That pause gave the dying Klearchos a last opening. On his way down, the broad-shouldered Spartan grabbed at Staphis’s thigh—just as Chiôn crossed over in front and in an instant finished off the falling Spartan with his spear.

Chiôn nearly tore Klearchos’s helmet off with a single thrust to the back of his neck. He pulled out far more gore than did Staphis. For the arms of the slave were as thick as the lower legs of the vine grower. Yet the dying Spartan—he was young and stout, this Klearchos, and like his father also of large arms and thighs and just as cruel—still clung to Staphis. Both arms were frozen around the Thespian’s shins in his final death grip. Klearchos would take Staphis down with him to the lower world. As the two intertwined, they rolled in the dirt and were smothered by the hobnails of dozens of oncoming Thebans. The killer Spartan opened his mouth, flashing his white teeth against his black beard as he gave up the ghost.

The last words of Staphis were a desperate shriek to his protectors at his side, “Mêlon, Mêlon, he kills me—

me apokteinei! apokteinei me!

Chiôn. Mêlon …” Then he disappeared. Even in this fluid final stage, Mêlon was pushed ahead by pockets of Thebans still in file. Might perhaps Staphis have risen back up and survived the stampede to come over him? No. When a hoplite went down, he rarely rose under the weight of his armor. Mêlon answered his own question. Once flat on the ground only the veterans survived if they could cover with shield and ride out the stomping above. Still, Mêlon for a blink had tried to withstand the pressure at his back, to ward off the thrusts in his face, to stop and grab an arm of the downed Staphis. But the farmer from Helikon was already buried amid legs, bodies, and shafts, as if he were a crushed rabbit in the coils of the long grass snake that had wrapped him from head to ankles.

Mêlon and Chiôn in the front ranks strode ahead, banging as much with their bosses as they stabbed with spears. Bora shattered for good. Mêlon was using the broken back end as a sword. In fury at the loss of his Staphis, Mêlon had switched weapons. He was swinging his shield sideways in offense, hitting Spartans with the rim, while he kept them back and protected himself by fending with the broken spear as if it were some long dagger, its butt spike and most of the shaft gone.

The lesser folk of Thebes, those who had chosen the safety of the middle ranks and back, saw even more of an opening. In their frustration at pushing rather than killing, some of these farmers tried to burst through their own ranks and beat the front line to the shrinking enemy circle, at last feeling a chance to boast about glorious war—and get a bit of Spartan blood splattered on their breastplates to show their womenfolk back home. The killing, all thought, was almost over and now easy. Thirty, maybe forty rows of the Thebans were deep inside or even beyond the enemy phalanx and spreading sideways among the files of the Spartans—if there were any files left to see. The greater danger for the advancing Thebans was mostly the dead at their feet, not the living in front. The soil was strewn with bodies and flotsam—cracked shields, broken spears, and the carnage of an army slowly being ground down as Spartan hoplites backtracked, tripped, fell, and were in turn stepped upon as their friends gave way.

For a moment Mêlon turned to his right, held his shield up high, and gave another hard bash to the neck of a falling Spartan. Leobotas, a royal cousin to King Agesilaos himself, had tumbled into the gap, grasping the waist of Chiôn. He hoped to take him down, as Klearchos had done to Staphis. But Chiôn was not like Staphis, and Leobotas was no Klearchos. Instead, the dying Leobotas was dragged along the ground. Chiôn paid Mêlon no attention nor did he pause for his help. He just quickened his pace. Without much bother, he slammed his shield rim on this nuisance, hard down on the neck of Leobotas between his backplate and helmet rim, cracking his upper spine in two. Freed from the mossy barnacle on his greave, a maddened Chiôn resumed his charge toward the king. No one heard him yell, “Off, dead man. Get below.” In battle, a wide arm like Chiôn’s was worth far more than fifty

plethra

of vines or two chests full of gold.

All these dying Spartan lords had names and past stories of brave kills in battle, and wives and children, and fathers as well, all in Holy Sparta under the shadows of Taygetos and Parnon to the south. But to the slave Chiôn, did any of their lineage and honor matter now? No more than the now dead Staphis, the vine man who had only wanted to do some big thing for his Thespiai. That Leobotas owned one hundred

plethra

on the Eurotas as it roared down from Taygetos, or that his grandfather’s grandfather Hippokratidas had speared nine Argives at the battle of Sepeia and then died over the body of Leônidas at Thermopylai, swinging his

klôpis

as he fell to one knee as the Persians sought to cut off the head of his dead king—all that meant nothing at all in faceless battle, battle without memory, class, heritage. No, again, this was the new age of Chiôn, where rank was earned, not given. This was his own

aristeia

as the towering slave slaughtered six of the Spartan elite on his frenzied path right through the royal guard. What did it matter to Chiôn that Staphis’s killer, the dead Klearchos, claimed his ancestor was an Agiad king—as if his exalted ghost would save him from a poxy slave from Chios?