The Epic of New York City (24 page)

Read The Epic of New York City Online

Authors: Edward Robb Ellis

In the seventy-year duel for empire, England had fought successive wars with France, partly in America and partly in Europe. A treaty signed in 1763 gave England control of North America from the Atlantic to the Mississippi and from Spanish Florida to the Arctic Sea. The wars had saddled the English with an enormous public debt.

British officials felt that the colonies ought to shoulder part of this load because now that Canada had been wrested from the French, the American provinces were no longer threatened by an invasion from the north.

Still, a few thousand French Canadians smoldered on the far side of the St. Lawrence River, and several hundred thousand hostile Indians bore watching. To guard this new empire, 10,000 British troops were to be sent to America, and the king's men thought the colonists should share this military expense. First, however, the English decided to break up the smuggling that put American customhouses in debt year after year.

The Navigation Acts would be enforced strictly, the colonies would be taxed, more power would be given to the admiralty courts, and royal governors would be told to demand compliance with the new acts pouring out of England. All these measures provoked the colonists, but they did not act in unison until the Stamp Act was passed in 1765. News of this outrageous law reached New York on April 11, 1765, and touched a spark to a long train of powder.

A

NGERED

by the Stamp Act, malcontents took direct action on April 14, 1765. They spiked the guns in the fort, then headquarters for England's small standing army in America.

During the recent Seven Years' War all the colonists had prospered, for British soldiers had spent money freely and contractors had reaped huge profits. However, after most of the troops had been withdrawn and the war contracts had been lost, there began a postwar depression, which was intensified by Parliament's trade acts. Prices soared. Real estate values fell. Creditors squeezed debtors. One

bankruptcy followed another until a New Yorker wrote: “It seems as if our American world must inevitably break.”

The Stamp Act was to go into effect on November 1, 1765. Unlike the new trade laws, it was meant not to control commerce, but to collect revenue. Under its terms Parliament insisted that the colonists pay direct taxes. In the past, taxes had been levied indirectly by imposing requisitions on colonial assemblies, which then appropriated the needed funds. Money raised by the Stamp Act would be used not to reduce the British debt, but to pay part of the cost of maintaining the 10,000 soldiers to be sent to America. Since this army would cost 350,000 pounds a year and the Stamp Act would yield only 60,000 pounds annually, British officials didn't feel that they were being unreasonable. Besides, the law would operate almost automatically. All legal transactions and various licenses would require a stamp.

The colonists didn't want a standing army in America. They weren't greatly concerned by the cost of the tax. What bothered them was the principle: taxation without representation.

Tax stamps were already used in England, but the situation there was different because the British were represented in Parliamentâafter a fashion. Twenty-nine out of every thirty Englishmen could not vote, but as William Pitt said, everybody at least had the right to cheer at elections. The colonists lacked even this fun, so New York newspapers shrilled with alarm, as did other American periodicals.

But what happened if the colonists refused to buy stamps? Well, they couldn't get a marriage license, buy a newspaper, draw up a will, receive a college diploma, file a lawsuit, purchase an insurance policy, send a ship from the harbor, or drink in a tavern. Even dice and playing cards were to be taxed. A total of forty-three groups of business and social transactions would require stamps, costing from twopence to ten pounds.

And who would collect the tax? Stamp mastersâAmericans, to be sure, but deep-dyed loyalists, who knew the right people in London. Each would be paid 300 pounds a year. There was a rush of applicants, but those chosen soon found themselves the most hated men in America. For example, Zachariah Hood of Maryland had his store demolished, was burned in effigy, and received threats against his life. Quaking with fear, he flung himself upon a horse and galloped toward New York, riding so hard that his steed died on the way. After getting another mount and reaching the city, he hid in Flushing. There he was discovered, however, and forced to resign his royal commission.

A New York paper soon published this tentative cry for independence:

If then the Interest of the Mother Country and her Colonies cannot be made to coincide (which I verily believe they may), if the same Constitution may not take Place in both (as it certainly ought to do), if the welfare of the Mother Country necessarily requires a Sacrifice of the most valuable natural Rights of the Colonies, their Right of making their own Laws and Disposing of their own Property by Representatives of their own choosingâif such really is the Case between Great Britain and her Colonies, then the Connection between them ought to cease.

The New York assembly was in recess when news of the Stamp Act arrived. The first formal defiance came from Virginia. In the house of burgesses, Patrick Henry bitterly denounced the bill and asked fellow members to pass seven resolutions, which he whipped out of his pocket. Although four were rejected, all seven were reprinted by colonial newspapers. Thus the Virginia Resolves, as they were called, fluttered up and down the coast, like burning leaves from a forest fire, and inflamed other hearts.

James Otis now proposed in the Massachusetts legislature that the thirteen colonies send delegates to New York to sit as a congress and discuss resistance to the Stamp Act. On October 7, 1765, twenty-seven men from nine colonies met in City Hall; Virginia, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Georgia were not represented. This Stamp Act Congress brought together rich men in coats of mulberry velvet and poor men clad in plain broadcloth. Collectively they were the best brains on the continent.

With its 18,000 inhabitants, New York had grown larger than Boston but still lagged behind Philadelphia. Under a new city law, householders had been ordered to cover their roofs with slate or tile to reduce the danger of fire, but the law was largely ignored. Visitors walking along flat-stone sidewalks and crossing cobblestone pavements praised the clean streets. They saw diamond-studded women and gentlemen dipping snuff from handsome snuffboxes and learned that many literate citizens read Shakespeare, Swift, Pope, Addison, and Hume.

Autumn is New York's most delightful season, but the delegates had little time to enjoy it. After gathering in City Hall, they soon divided into two factionsâradicals and conservativesâand for the next three weeks debated how to act toward the mother country. At

last they drew up resolutions of colonial “rights and grievances” and petitioned the king and Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. They declared that taxation without consent violated one of an Englishman's most precious rights, and they still considered themselves Englishmen.

On Ocober 22, while the congress conferred, the ship

Edward

arrived from England with the first stamps consigned to New York, packed inside ten boxes stowed in various parts of the vessel. Their arrival was announced at 10

P.M

. by the thunder of cannon from a man-of-war in the harbor. The next morning the

Edward

docked at the Battery. Two thousand people flocked there to jeer, so nervous officials did nothing until the crowd had dispersed. Later that night seven boxes were unloadedâthe fear of a rising wind cut the work shortâand transported secretly to the fort.

The next day dawn broke on rude posters nailed here and there in town. These warned: “The first man that either distributes or makes use of stamp paper, let him take care of his house, person and effects.” Signed

Vox Populi,

the posters added: “We dare.” The threat frightened the elderly scientist Cadwallader Colden, the new and unpopular lieutenant governor. He postponed opening the boxes until the just-appointed governor, Sir Henry Moore, arrived. Apparently Major Thomas James, who commanded the fort, thought differently. He was quoted as saying he would “cram the stamps down the throats of the people” with the end of his sword. By then more munitions and men had been added to the fort. Clad in scarlet coats, white breeches, and cocked hats, infantrymen and artillerists stirred restlessly and wondered what would happen next.

On October 31â”the last day of liberty,” the patriots called itâroyal governors throughout America swore to enforce the Stamp Act. At 4

P.M

. more than 200 New York merchants met in George Burns' tavern at Broadway and Thames Street and signed an agreement to boycott British goods until the act was repealed. This, the first of the historic nonimportation agreements, laid the foundation of American manufacturing. The New York

Gazette

declared in huge type: “IT IS BETTER TO WEAR A HOMESPUN COAT THAN LOSE OUR LIBERTY!” Crowds clattered over cobblestones, shouting threats and singing defiant ballads. They were led by direct actionists, calling themselves the Sons of Liberty. James McEvers, the city's stamp master, looked, listened, and resigned. Lieutenant Governor Colden hid inside the fort.

The next day the Stamp Act was supposed to go into effect. However, the stamps were not distributed. Many offices remained closed. Buildings were hung with black crepe. Even backgammon boards and diceboxes in the Merchants' Coffee House were shrouded in black. Flags dangled at half-mast. Muffled church bells tolled. Again a street crowd gathered to mutter and grimace. Now, for the first time in the city's history, there appeared a new phenomenonâthe mob. City magistrates warned Colden that they feared an outbreak. Marines disembarked from warships, and soldiers dogtrotted from Turtle Bay on the East River, bringing the fort's strength up to 30 officers and 153 enlisted men. As the day wore on, city merchants, barbers, sailors, cartwrights, teamsters, blacksmiths, and tavernkeepers were augmented by farmers, who streamed in from the countryside. By 7

P.M

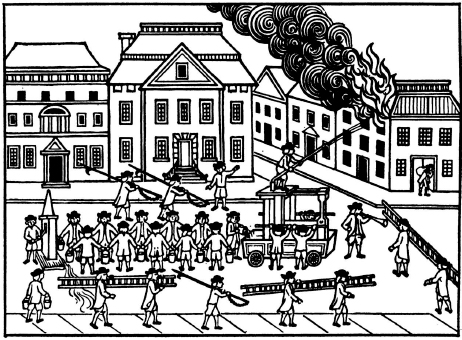

. all came together on the Commons.

There the Sons of Liberty whipped them into a frenzy as darkness fell. Torches, lanterns, and candles were lighted, their smoke idling straight up into the windless sky. Working by the glow, the mob made an effigy of the gray-haired lieutenant governor holding a stamp in one hand and then hung the figure from a mock gallows. Next, an image of the Devil was constructed and thrust so close to the figure of Colden that Satan seemed to be whispering into his ear. Both effigies were hooted and jeered. Now they were put in a cart and trundled onto Broadway. Men shot pistols at them. The shouting, dancing, disorderly crowd churned down Broadway toward the fort. Colden's coach house lay just outside its walls. The mob broke in, hauled out the lieutenant governor's gilded coach, and transferred his effigy to its top amid wild cheers.

Colden, hearing these shouts from within the fort, sagged in terror. Before the mob arrived, soldiers had sallied forth and knocked down a wooden fence in front of the fort so that rampart-posted gunners could potshot attackers. Torchbearing screaming men now scrambled over the broken boards and surged toward the fort. From a rampart, Major James cried, “Here they come, by God!” Men hefted heavy timbers to batter at the fort's doors. Bricks and rocks were thrown at parapets and ramparts. Faces distorted in fury, the rabble dared the cannoneers to fire. Major James stepped forward for a better look. Seeing him above their heads, the crowd bellowed with renewed anger. Again they lunged forward. Royal gunners held matches near the touchholes of their cannon. A massacre seemed to be in the making.