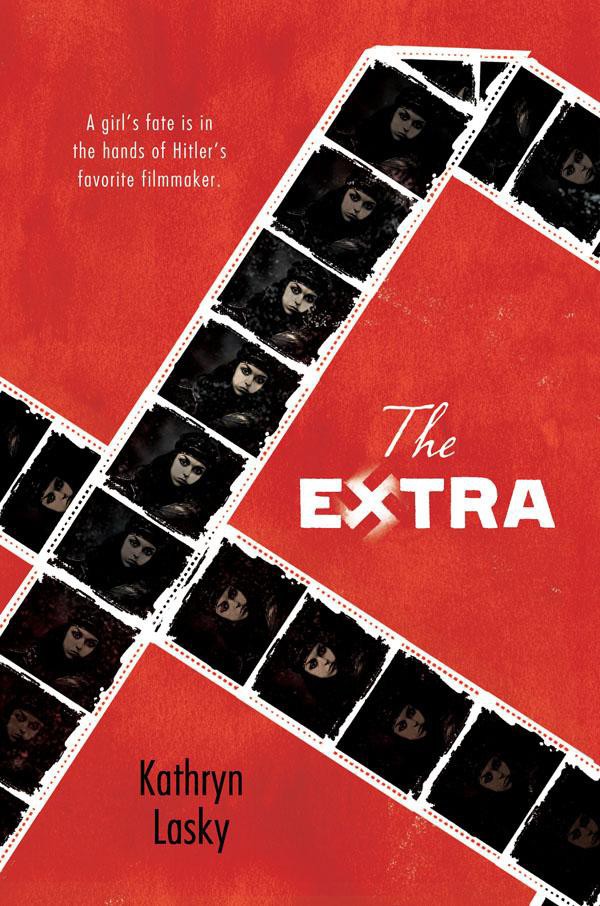

The Extra

“D

isappeared? What are you talking about? People don’t disappear. She just went someplace.”

“So where do you think Mila went? Why wasn’t she in school? Today of all days, recitation day. She had been practicing forever. She was sure to get the prize.”

“Maybe she’s sick.”

“Mila sick? Never — she’s healthy as a horse. And even if she is, she would have dragged herself to school. No — something’s fishy.”

Lilo shut her eyes. If only Hannah didn’t live in the same neighborhood. Then they wouldn’t have to walk home together. She was always thinking the worst. It was too depressing. There was something slightly perverse about her. She seemed to almost enjoy bad news. There was always this “I told you so” attitude.

“I think the Nazis got her,” Hannah said. “Your fingers still purple?”

Two weeks before, Lilo’s family and all the other Gypsies over the age of fourteen in Vienna had been required to report to the police headquarters to be fingerprinted. It was all part of the Nazi laws, the Nuremberg Laws. Now the Nazis knew who they were and where they lived. That was frightening.

“Uh . . .” Lilo hesitated. “I really haven’t tried to wash it off.”

“Lilo! Are you telling me you haven’t bathed in two weeks, washed your hands in two weeks?”

“No, of course not!”

“Well, I can see they are still purple.”

“So why did you ask?”

Hannah shrugged. “Well, I have tried to get it off. My mum, my dad, my brother, and I have tried everything — spirits of camphor, nail-polish remover mixed with scrubbing salts. Nothing works.”

Lilo took a sharp left. “Hey, where you going?” Hannah said. “Home is straight ahead.”

“My father’s shop. I forgot he wanted me to stop by.”

“All right, hope I see you tomorrow. I mean I hope we both see each other tomorrow. Could be you. Could be me.” She shrugged again.

“Maybe Mila will be back,” Lilo replied.

“You know she’s not the first to disappear. An upper-grade girl, Zorinda, is gone, too.”

But Lilo didn’t want to hear any more of it. The church on the corner ahead marked the intersection of the street they were on and the one for her father’s shop. Kirchestrasse was a cobbled lane more than a street. She rushed down it and turned in under the sign of the clock. On the window was a seal, the seal of the Imperial Clockmakers Guild of Vienna, with three stars designating him as a master clockmaker and licensed dealer in antique timepieces.

“Papa!” she called out as she came into the small shop that was not much bigger than a closet. A chorus of ticking clocks and all kinds of watches greeted her. The sounds of the timepieces stippled the air.

“Papa!” It was more of a yelp than a cry. The shop was open, but he wasn’t there.

“Papa!” she now bellowed. She heard footsteps.

“What in the world!” Her father came through a back door.

“Where were you? I was so worried.”

“I’m fine — I’m here. What were you worried about? Can’t a fella take a leak? I just went to the toilet.”

She smiled. Everything was all right. Her father stood before her, the little green eyeshade he always wore pushed up, the jeweler’s loupe hanging on the black ribbon around his neck, his tie tucked into his vest so it would not interfere as he took apart and put back together all manner of watches and clocks. His fingers were still purple, too, she noticed.

“Papa, do you have any of that lubricating oil you use for the escapement wheels?”

“Sure, but what do you want with that?”

“I had an idea that maybe if we mixed it with alcohol, we could remove the stains on our fingers.”

“Doubtful, but if you want to try, go ahead.”

She stood over a small basin and poured the oil first and then the alcohol. “Can I use this sponge?”

“Sure. I’ll be finished here in a couple of minutes. Then I just have to pack up a few things to take home to work on. The baron is coming by tomorrow for his watch.”

“The tsar’s watch.”

“That’s the one.”

“Must be very valuable,” Lilo said. She had now forgone the sponge and took up a wire brush that her father often used for cleaning his tools. She began scrubbing harder. “Ouch!”

“What’s wrong?”

“Nothing.”

A tiny bead of blood popped up where she had been scrubbing. One of the wires must have stuck right through her skin.

Great,

she thought,

I’ll probably get blood poisoning now from the damn purple dye going directly into my veins.

Five minutes later, they were walking out of the narrow street and onto a broader avenue. “Feels like summer, doesn’t it?” her father said.

“If only!” Lilo sighed.

“Don’t worry. Summer will be here sooner than you think.”

“It seems like a tease,” Lilo said.

“What?”

“You know, when it’s warm like this, but the days are growing shorter so fast. It’s nine more months until summer, Papa.”

“Ah, it will go quickly.”

“Look at this!” her mother said as they came into the apartment. She waved a photograph in her hand. “From Uncle Andreas.”

“Oh, let me see! Let me see!”

It was a picture of Lilo on Cosmos, the beautiful Lipizzaner. Suddenly summer seemed further away than ever. And Piber as far as the moon. Her uncle Andreas was the head trainer at Piber, the stud farm for the famous Spanish Riding School of Vienna. And every year they visited him for two weeks. With her uncle’s coaching, she had learned to ride. It was on Cosmos’s long back that she had mastered the first movement of the White Ballet, a classic in the Riding School repertoire. In Vienna only men rode the horses, but at Piber women were allowed to hack the old stallions that had been retired from stud services. She set the photograph on the table, propped up against a flower vase. Her mother came over and ran her hand across the back of Lilo’s head. “Lovely picture, isn’t it? Much better than the drawing I did of you on Cosmos.”

“No, Mama, that’s not so. You were trying to catch me when I was doing the first set of the dance steps. That was harder. Here Cosmos is standing still.”

“Much schoolwork?”

“Some.”

“Some?”

“Some, yes. That means between zero and much.”

“Well, you should get started,” her mother said, and gave her a pat on the head.

But it was hard to get started. The window was open, and a soft breeze blew through the lace curtains, sunlight casting an embroidery of shadows on the polished table. It was as if the low-angled setting sun of the autumn was determined to be remembered and make a show of itself. She traced the shadow design lightly with her pencil, careful not to mark the table. She set down the pencil and examined the stains on her fingertips. Dared she even hope about Piber?

Had her uncle Andreas been fingerprinted as well?

“Lilo!” her mother called. “Are you daydreaming?”

“It’s too hot to study.” Lilo looked at her parents. “There are kids out there swimming in the canal.”

“Must be Roma girls,” her mother muttered.

“Mama!” Lilo complained. “Look at Lori — she’s Roma. You love Lori. She doesn’t dress racy. She doesn’t wear makeup. She is one of the smartest girls in the class, and her family does not travel around in a caravan. They live in an apartment twice the size of ours.”

“She’s an exception. And I bet you there’s Sinti blood in that family somewhere.”

Lilo sighed. Sometimes her mother was so narrow. “Look at Papa — he plays the violin at the best restaurant. Sinti aren’t supposed to be musical, remember? Mr. Gelb is begging him to play more nights. Says he’s better than Molder, who is Roma. So for all you know, we might have some Roma blood!”

“Lilo!” her mother exclaimed. “Fernand, did you hear what your daughter just said?”

“What?” he answered distractedly.

Lilo looked at her father. He was bent over the escapement wheel of the priceless antique watch of the tsar.

“She said maybe you have Roma blood, since you play the violin so well.”

“Hmm, that’s interesting.” He was completely absorbed filing the teeth of the wheel. Lilo liked to hear the rasp of the file.

It was the rotation of the escapement that powered the timekeeping element. Her father wound it now and set it down to give it a try. A new sound. A tiny ticking as the wheel turned, allowing the gears to move, or “escape” a fixed amount with each tooth of the wheel. He’d fixed it! In some ways, to Lilo her father was a magician. He could fix time. Manipulate it. Save it!

Without the escapement, time would stop or perhaps run away, Lilo wasn’t sure. When her father had explained this to Lilo when she was very young, she had imagined time running off like the gingerbread man. The tune and the lyrics began to run through her head now.

Run, run, run as fast as you can.

You’ll never catch me — I’m the gingerbread man.

I ran from the baker and from his wife, too.

You’ll never catch me, not any of you.

The baker made a boy one day,

Who leaped from the oven, ready to play.

He and his wife were ready to eat

The gingerbread man who had run down the street.

She always imagined pieces of watches — the gears, the jewels, the numbers on the face — running willy-nilly down the twisting streets of Vienna.