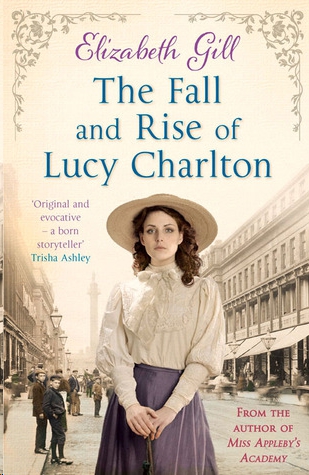

The Fall and Rise of Lucy Charlton

Read The Fall and Rise of Lucy Charlton Online

Authors: Elizabeth Gill

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Family Saga, #Historical, #Romance, #20th Century, #Sagas, #Historical Fiction

Question & Answer with Elizabeth Gill

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Quercus Editions Ltd

55 Baker Street

7

th

Floor, South Block

London

W1U 8EW

Copyright © 2014 Elizabeth Gill

The moral right of Elizabeth Gill to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78087 849 2 (PB)

ISBN 978 1 78087 850 8 (EBOOK)

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

You can find this and many other great books at:

www.quercusbooks.co.uk

In memory of all the wonderful moggies we had over the years. Among them were Dickens and Spider, Thomas, Dogtanian, Lucky Randolph and Little Miss Tabbytoes, who for obvious reasons went by the slick name of Kitty.

Durham City, 1919

Lucy Charlton went home to Newcastle for her sister’s wedding. The preparations for the wedding were all that her mother and Gemma had talked about for months. The wedding dress was the most important thing of all. Gemma and her mother had chosen the dress in a shop in Grainger Street and Gemma wanted her sister to see it. She was going for her final fitting the first afternoon that Lucy was at home.

The inside of the shop was hushed. As they entered it a fair-haired woman came out from an inner door and ushered Gemma away. Lucy sat down on a big sofa. Another woman appeared and offered Lucy tea. After a few minutes Gemma came out of the fitting room. Lucy couldn’t help but stare.

The dress made her sister look like a doll. Her cheeks were flushed, her eyes were bright and her hair was so shiny that it looked like a wig. Her fluttering hands and the cream satin material set her beyond reality. Lucy was astonished. The dress ended just above the ankle with wide skirts, like a

three-tiered cake. It didn’t suit her. In the cap with a trailing veil, Gemma looked tiny and scared, but Lucy knew what she must say – the anxious eyes of her sister told her so.

‘It’s beautiful,’ she said. ‘It’s so lovely … and you look just right in it.’

‘Do I?’ Gemma said, hesitating. She needed Lucy to say more, to say that she had never seen another bride who looked better, so she did. She could hear the echo of her voice afterwards; she hoped it did not sound as hollow as she thought it did. Was that envy? She could never look that way. Gemma turned and turned like the figure in a musical jewellery box when you lifted the lid and some plaintive air came forth to jangle at your nerves.

Round and round she went and Lucy sat there, admiring and anxious, yet when Gemma had gone back in the room to change Lucy found that she was shaking, and it was not the kind of problem a cup of tea would solve.

Finally, when the seamstress was happy with the dress, they left. Lucy was glad of the air and suggested they should go to Pumphreys in the Cloth Market and have coffee. Pumphreys always smelled so good with the coffee roasting. The windows there were intricate green glass and the sofas red velvet.

They sat down at a table near the back of the room and she said to her sister, ‘Are you feeling all right?’

Gemma looked offended. ‘What do you mean?’ But Gemma didn’t let Lucy get any more words out. She looked down at the table and she said, ‘I know you don’t want me to marry. You’ve made it perfectly obvious and I wish now that I hadn’t asked you to be my bridesmaid even though

you are my sister. You pretend that you like Guy but it’s so obvious that you don’t. You hardly ever come home and you never answer my letters and you don’t seem to want to be associated with us as if we are beneath you somehow now that you’re at university with all your clever friends in Durham.’

‘Gemma, that’s not true!’ Lucy exclaimed, horrified.

Gemma turned to her, eyes glassy with tears. ‘Guy is a perfectly nice man and I’m sorry that you’re jealous of him but really you know we cannot go on as we are. Don’t you understand anything?’

‘I don’t know what you mean.’

‘Of course you don’t. You never think about anybody but yourself. Father isn’t well and we have no money. All I have is that I can marry a respectable man who will help us, but you … you …’ Gemma got up and ran out of the coffee house.

Lucy stared, astonished, as the customers watched; some of them had turned around, teacups or cake in hand. Then she got up and ran after her sister, but it was not easy. Gemma set a good pace and they were most of the way home when Lucy, panting, caught up with her.

Gemma had stopped, by then, out of breath.

Lucy could not help saying, ‘What happened to the money? Daddy is a wonderful lawyer. He makes lots of money.’

Gemma looked at her from pitying and rather glassy eyes. ‘He isn’t making enough any more. He gets very tired. He isn’t well and he has to pay for my wedding and for your stupid university course or whatever you call it. You were never happy with how things were, always wanting to change

everything. Nothing was good enough for you and now look.’

‘What is wrong with Daddy?’

Gemma shook her head and took her handkerchief from her pocket. She spent a long time wiping her eyes and blowing her nose, turned half away from Lucy. Finally she screwed the handkerchief into a soggy ball and returned it to her pocket, her cheeks still wet with tears.

‘Nobody seems to know and you mustn’t say anything because we aren’t supposed to be aware of it. Mother kept it from me until I found Daddy wandering around the living room, confused. He doesn’t remember things as well as he did. But Mother is happy now I’m marrying Guy. She won’t have to worry about anything any more because Guy has money.’

Lucy could not imagine that her father was ill and she did not know it. She had always been closer to him than Gemma. In a way Gemma was her mother’s child and she was her father’s. Lucy had always been very much aware that her father had dearly wanted a son and she had tried to be that son. She had thought she was doing the right thing; her father was proud of her for being so academically clever and one of the first women ever to go to Durham University to study law.

Lucy had seen the light in his eyes and even though it had been very hard to leave when she wanted to be here with him, in his office and by his side, she had left because it was the only way she could study law and make him happy. Now she felt as if she had done the wrong thing.

She looked again at her sister. Gemma had always been beautiful – red-haired, creamy-skinned, eyes like emeralds

– and she was a pale imitation – tall and rangy rather than neat and slim, her eyes darker, her hair not quite blonde and not quite red and frizzy. It didn’t matter what she did with it, it could not be tamed. Now Gemma was thin and pale and sad about their father and Lucy wanted to put an arm around her except that Gemma would have shrugged it off.

‘But you do want to marry Guy?’ She immediately wished she could take back the words, but they needed to be said.

Gemma’s face was flushed with tears. ‘I like him very well.’

It was a sentence that Lucy did not forget.

‘It’s easy for you,’ Gemma said and she walked away.

Lucy couldn’t imagine how her sister thought that things were easier in Durham except that she had been able to leave home other than to marry, but she knew that was not something Gemma had ever wanted. She caught up with her sister and they walked slowly home and didn’t speak at all.

*

Lucy had dreaded Gemma’s wedding day and now she knew why. Gemma was obliged to marry well and Lucy no longer wondered why she did not care for the sound of Guy’s voice in the hall. She wished he had done something which would pinpoint him as the enemy so she could say to Gemma that she must not marry him, but she could see things so much more clearly now than she ever had before. Her parents had nothing but the damp house beside the river. Her grandfather had died young and her father had had to keep his mother and his sisters and all of his family too. Their house beside the Tyne was very slowly sinking into the sand, into

the silt, into the very river itself. She felt it was sinking beneath her expectations.

It was the night before the wedding and the house was full of presents. Gemma had been keen to open them and couldn’t wait for Guy to arrive. When he did, he laughed and said it would be all table napkins and that he had no interest in such things. There were velvet canteens of cutlery and tall vases in red and purple which Gemma grimaced at.

Gemma exclaimed afresh at each opened gift. Lucy had no more interest than Guy in silver and crockery, but she had to admit that the dinner service would look good upon the oak table which Guy’s parents had given them as a wedding present, along with a dozen chairs. They were buying a modest house in Jesmond, which Gemma had not offered to take her sister to visit.

Lucy’s bridesmaid dress had flounces. Guy’s sister and his three cousins were to wear the same peach-coloured outfits with little bonnets with orange ribbons tied under their chins. They would carry small baskets from which they would strew the aisle with rose petals, the last from Guy’s mother’s garden. She had kept them aside for this very occasion; they were cream and yellow and orange to suit. Lucy was silently appalled. She thought she looked like Little Bo Peep.

Lucy had become aware that her parents were paying for everything; her mother was always with lists about her – how many people were attending and what flowers would adorn the church, the pews, the altar. The reception could not be at their home, to her mother’s chagrin, as it was not big enough to accommodate all Guy’s relatives and friends. Instead it was to be at a huge hotel in Newcastle, not a usual

idea, but her mother was proud that they had managed to afford it.

After Gemma had opened the presents, Guy had taken her to visit some relatives. It was usual for the groom to drink deeply on the eve of the wedding and for the bride to stay at home, but he had so much wanted Gemma to meet his mother’s family from Kent that she had gone there for the evening.

They were late. Lucy lay awake, listening for her sister coming home, thinking that Gemma would not be there again, that their childhood and her place in her sister’s life was set back and altered forever.

Lucy heard Gemma say something as they returned to the house. It was sharply uttered and Guy said something also. She heard her sister’s footsteps come up the stairs and the door was closed quietly. She thought she heard something more downstairs. She put on a robe. She almost didn’t go, but in the end she could not rest; she thought that perhaps Gemma had left her purse and Guy had discovered it in his motor, so she went down in the darkness and opened the front door. There was no light outside. She was about to go back when she saw Guy and she moved forward, beyond the house.

‘Has Gemma forgotten something?’ she said.

‘Nothing.’

Lucy was about to go back inside when he came quickly to her and put his arms around her. Lucy pushed back from him.

‘What on earth are you doing?’ she said. She could smell the alcohol on him.

He gathered her against him and kissed her, and through

the material of his clothes and her nightwear she felt his body, warm and urgent, and her own senses screaming at her to move away. He was drunk; young men did such things. Perhaps that was what the raised voices had been before Gemma came inside. She pushed at him with both hands, thinking this would be the last of it and they would smile at it tomorrow when he had a sore head on his wedding day, but he did not let her go. His mouth became cruel, his tongue probing her teeth. She had not reasoned that a man was so strong. She had never had to think about how strength might be used against her.