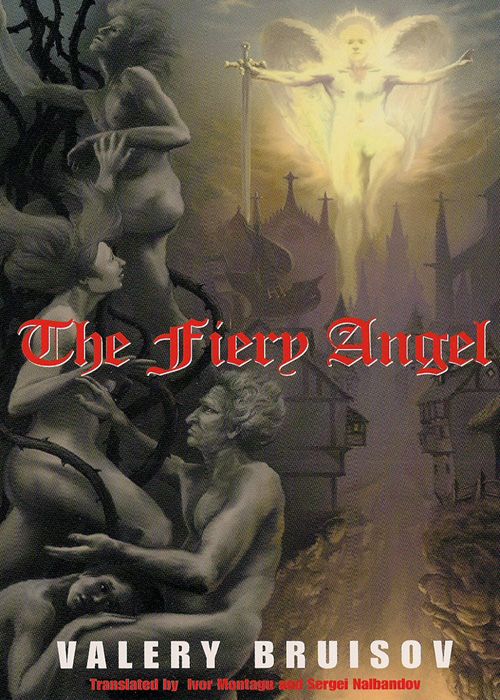

The Fiery Angel

Published in the UK by Dedalus Limited,

24–26, St Judith’s Lane, Sawtry, Cambs, PE28 5XE

email: [email protected]

ISBN printed book 978 1 903517 33 8

ISBN e-book 978 1 909232 79 2

Dedalus is distributed in the USA & Canada by SCB Distributors,

15608 South New Century Drive, Gardena, CA 90248

email: [email protected] www.scbdistributors.com

Dedalus is distributed in Australia by Peribo Pty Ltd.

58, Beaumont Road, Mount Kuring-gai, N.S.W 2080

email: [email protected]

Publishing History

First published in Russia in 1908/9

first published in England in 1930

First published by Dedalus in 2005

First ebook edition in 2013

This edition copyright © Dedalus 2005

Printed in Finland by Bookwell Ltd.

Typeset by RefineCatch Limited

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The Fiery Angel or a True Story in which is related of the Devil, not once but often appearing in the Image of a Spirit of Light to a Maiden and seducing her to Various and Many Sinful Deeds, of Ungodly Practices of Magic, Alchymy, Astrology, the Cabbalistical Sciences and Necromancy, of the Trial of the Said Maiden under Presidency of his Eminence the Archbishop of Trier, as well as of Encounters and Discourses with the Knight and thrice Doctor Agrippa of Nettesheim, and with Doctor Faustus, composed by an Eyewitness.

Amíco Lectorí

The Author’s Foreword in which is related his Life prior to his Return to German Lands

I

T is my view that everyone who has happened to be witness of events out of the ordinary and not easily comprehensible should leave behind a record of them, made sincerely and without bias. But it is not only the desire to advance so intricate a matter as the study of the mysterious powers of the Devil, and of the spheres permitted to him that induces me to embark upon this unadorned narrative of all the marvellous events I have lived through during the last twelve months. I am attracted also by the possibility of opening my heart in these pages, as if in dumb confession before an ear unknown to me, for I have no one to whom my tragic story may be uttered, and, moreover, silence is difficult to one who has suffered much. In order, therefore, that you, gentle reader, may see how far you may have confidence in my guileless story, and to what degree I was able rationally to appreciate all that I witnessed, I desire, in short, to set out my tale.

First I shall explain that I was no youth, inexperienced and prone to exaggeration, when I encountered that which is dark and mysterious in nature, for I had already crossed the line that divides our lives into two parts. I was born in the Kurfürstendom of Trier at the beginning of the fifteen hundred and fourth year after the Materialisation of the Word, February the fifth, St. Agatha’s day, which happened on a Wednesday, in a small village in the valley of Hochwald in Losheim. My grandfather was barber and surgeon in the district, and my father, having obtained for the purpose the privilege of our Kurfürst, practised as a physician. The local inhabitants always highly esteemed his art, and probably to this day, when ill, they have recourse to his attentive care. There were four children in our family: two sons, including myself, and two daughters. The eldest of us, brother Arnim, having studied with success his father’s craft, both at home and in the schools, was received into their corporation by the Physicians of Trier, and both my sisters married well and settled down: Maria at Merzig and Louisa at Basel. I, who had received at Holy Baptism the name of Rupprecht, was the youngest of the family, and still remained a child when my brother and sisters had already become independent.

Of my education I must speak in some detail, for, though I forfeited school tutelage, yet I do not consider myself any lower than some of those who pride themselves on a double or a treble doctorate. My father dreamed that I should be his successor, and that he would hand down to me, like a rich heritage, both his practice and the respect in which he was held. Almost before he had taught me to read and write, to count upon the abacus, and the rudiments of Latin, he began to introduce me to the mysteries of the preparation of drugs, to the aphorisms of Hippocrates and the book of Iohannitius the Syrian. But from childhood, all sedentary occupations requiring no more than attention and patience have been hateful to me. Only the insistence of my father, who held to his purpose with senile stubbornness, and the pleas of my mother, a woman of kindness and timidity, forced me to achieve a measure of success in the matters studied.

For the continuance of my education, father, when I had reached fourteen years of age, sent me to the City of Köln on the Rhine, to his old friend Ottfried Gerard, thinking that my application would increase by competition with my school-fellows. However, the University of that city, from which the Dominicans were just then conducting their shameful dispute with Iohann Reuchlin, was ineffective in stimulating in me a special zeal for learning. In those days, though some reforms had been begun, there were among the docenti practically no followers of the new ideas of our time, and the Faculty of Theology still arose amongst the others like a tower over roofs. I was made to learn by heart hexameters from the “

Doctrinale

”of Alexander and to penetrate into the dead “

Ars Dictandi

” of Boethius. And if I learned something during the years of my stay at the University, it was certainly not from the lectures of the schools, but only from the lessons of the ragged, wandering tutors who appeared from time to time in the streets of Köln itself.

I must not (for that would be unfair) describe myself as devoid of abilities. True, often was I tempted from the working desk and the binding of asses’ skin—away into the mountains and forests, to the rustle of verdure and the wide and distant spaces, yet, endowed with a good memory and quick understanding, I have later been able to gather together a sufficient stock of information and enlighten my intellect by the rays of philosophy. What I have since chanced to learn of the works of the Nürembergian mathematician Bernhard Walther, of the discoveries and reflections of the doctor Theophrastus Paracelsus, and still more of the entrancing views of the astronomer Nicolaus Koppernigk living in Frauenburg, enables me to think that the beneficent revival that in our happy age has regenerated both philosophy and the free arts may one day move to the sciences. (But these must be familiar to everyone who confesses himself, in spirit at least, a contemporary of the great Erasmus, wanderer in the valley of the humanities,

vallii humanitatis

.) In any case, both in the years of my youth—unconsciously, and as adult—after reflection, I never set high store by learning gathered by new generations from old books and not verified by the investigations of experience. And, together with the fiery Giovanni Pico di Mirandola, author of the divine “Discourse on the Honour of Man,” I am ready to pour out my curses upon the “schools where men busy themselves in seeking new words.”

Avoiding the University lectures at Köln, I threw myself, however, with the more passion into the free life of the students. After the strictness of my paternal home, I found to my taste the gay drinking, the hours with frail companions, and the card games that take one’s breath away by their sudden turns of fortune. I quickly familiarised myself with these riotous pastimes, and with the general noisy bustle of the city, filled with eternal fuss and hurry, that are the characteristic peculiarities of our days, and on which our elders look, puzzled and incensed, remembering the quiet times of the good Emperor Friedrich. Whole days did I spend in pranks with my bosom friends, days not always innocent, migrating from drinking house to bawdy house, singing students’ songs and challenging the artisans to fight, and not averse from drinking neat brantwein, a practice that fifteen years ago was far less widespread than now. Even the moist darkness of the night, and the tinkle of the street chains being fastened, did not always send us to our rest.

Into such a life was I plunged for nearly three winters, until all these diversions came near to ending unhappily for me. My untried heart flared up with passion for our neighbour, the baker’s wife, sprightly and pretty—with cheeks like snow strewn with the petals of roses, lips like corals from Sicily and teeth like pearls from Ceylon, if one may use the language of the poets. She was not disinclined to favour the youth, upright and sharp of repartee, but she desired from me those small presents, of which, as remarked Ovidius Naso of old, women are ever greedy. The money sent me by my father was insufficient to satisfy her capricious tastes, and so, with one of my wildest school-fellows, I became involved in a very nasty business, that did not remain undiscovered, so that I was threatened with imprisonment in the city gaol. Only owing to the strenuous intercessions of Ottfried Gerard, who enjoyed the goodwill of that influential Canon of distinguished intellect Count Hermann von Neuenar, was I freed from the trial and sent home to my parents for domestic punishment.

It was then that there began for me that unscholastic schooling to which I am indebted for the right to call myself an enlightened man. I was seventeen. Not having received at the University even a bachelor’s degree, I settled down at home in the miserable state of a parasite and a disgrace, shunned by all. But I found in our secluded Losheim one true friend, who loved me humbly, who soothed my embittered soul and led me on new paths. He was the son of our apothecary, Friedrich, a youth, slightly older than I, ailing and strange. His father loved collecting and binding books, especially new ones, printed ones, and he spent on these all the surplus of his income, though he read but seldom. But Friedrich gave himself up to reading as to some maddening passion, he knew no greater ecstasy than to repeat aloud his beloved pages. And when I was not wandering with an arbalist over the crests and slopes of the neighbouring mountains, I used to visit the tiny garret of my friend, at the very top of the house, under the tiles, and there we would spend hour after hour surrounded by the thick tomes of antiquity and the slender volumes of our contemporaries.