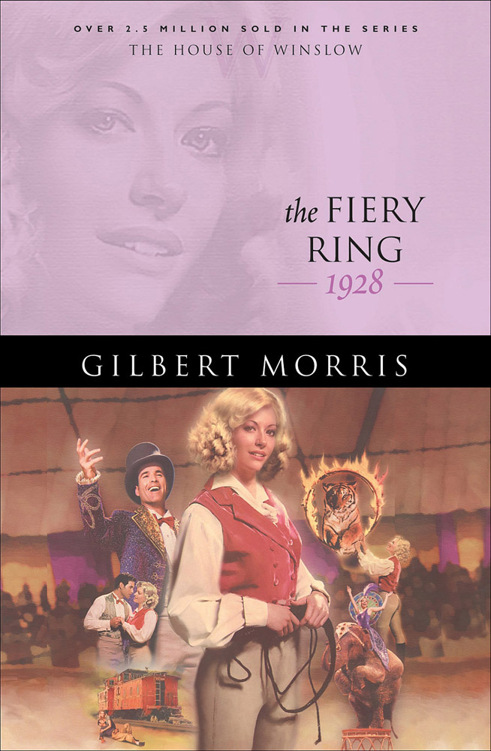

The Fiery Ring

Authors: Gilbert Morris

© 2002 by Gilbert Morris

Published by Bethany House Publishers

11400 Hampshire Avenue South

Bloomington, Minnesota 55438

Bethany House Publishers is a division of

Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Ebook edition created 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

ISBN 978-1-4412-7053-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Unless otherwise identified, Scripture quotations are from the King James Version of the Bible.

Cover illustration by Bill Graf

Cover design by Josh Madison

TO RICKY LEACH

Nothing gives me more pleasure than to see a young man or woman begin a pilgrimage with Jesus—and especially those in my own family. I pray that you will be used in a mighty way for our wonderful Saviour for many years. He who has begun a good thing in you will surely complete His work. Love the Lord with all your heart and strength and might, Ricky, and run with patience the race that is set before you.

CONTENTS

2. “You Can Have Anything You Want!”

CHAPTER ONE

Promised Land

The land lay flat in every direction, the horizon unbroken by mountains or hills, the gray land meeting an even grayer sky in an invisible seam. Two figures made their way across this vast openness, looking out on their dull, colorless world. Behind the pair, a quarter of a mile away, the monotony of the land was interrupted by the outline of a house, a barn, and a windmill, and even more faintly by a fence enclosing livestock.

Only the crunch of their boots in the snowy field of stubble disturbed the silence. The air was bitter cold, reddening their cheeks. The man wore overalls, a heavy dark brown coat, and a cap with flaps over his ears. The young girl beside him wore a long skirt over her boots and a plaid mackinaw. Her bright red scarf made a vivid crimson splash on the colorless world.

“I guess this ought to do it, Joy.”

Bill Winslow fished in his pockets and produced two tin cans. He placed them on an upended ancient wooden apple crate, weathered to a pale silver. Turning to the girl, he smiled and winked at her. “Think you can hit anything today?”

“Sure I can, Dad.” Joy Winslow took off her right glove and pulled a nickel-plated thirty-eight out of her pocket. “All loaded,” she grinned. “I bet I hit better than you do today.”

Winslow, a tall, lean man of forty-eight, had a pair of searching brown eyes and a face tanned by the sun and hardened by the wind. Small creases edged the corners of his eyes, and his wide, generous mouth turned upward in a smile as

he studied the girl.

Hard to believe she’ll be sixteen in a few months. Seems only yesterday she was just a baby.

“Bet you don’t,” he said. “I feel sharp today. Come on, we’ll go back an extra ten paces.”

The two moved away from the target, and when they halted, Joy held the thirty-eight firmly in her right hand and placed her left underneath. She held the pistol steady for two or three seconds, then squeezed the trigger. The explosion reverberated across the empty field, flushing out a flock of crows from the stubble. Rising with raucous cries, the birds formed a black cloud against the neutral gray of the sky. One of the tin cans lay on the ground.

“I got it, Dad!” Joy cried. Her eyes were laughing as she turned to him and said, “Bet’cha can’t beat that.”

“I’m not sure I can. You’re a regular Annie Oakley.” Bill aimed carefully at the second can with the forty-four but missed. He laughed and put his arm around her, pulling her close. “You’re a fine shot, daughter. All right, your turn again.”

The two fired at the tin cans for twenty minutes, laughing at their misses and shouting when they hit their target. Finally Bill said regretfully, “Reckon we better be getting back to the house.”

“All right, Dad.” Joy removed the spent hulls from her pistol, and as she did, Bill said, “I want you to have that thirty-eight for your own, Joy.”

“You’re giving it to

me,

Dad!” Joy exclaimed, astonishment sweeping across her face.

“Sure am—and the forty-four goes to Travis. I know you’ll keep them always because they’re more than just two pistols. They’re part of our family history.”

“I know,” Joy murmured. She looked at the thirty-eight and then glanced up. “This belonged to my uncle, didn’t it?”

“Yes, Lobo Smith. He carried it when he was a federal marshal under Judge Isaac Parker in Oklahoma Territory.”

“Do you think he ever actually killed anybody with it, Dad?”

“Wouldn’t be surprised. He’s peaceable enough now, but he was pretty wild when he was younger.”

“I’d like to meet him. Do you think we ever will?”

“Maybe someday.” Bill quickly changed the subject. “This forty-four belonged to your grandfather, Zack Winslow. Zacharias, his name was. He fought in the Civil War. When he came home he did a lot of things. He went prospecting for gold out west and later became a successful rancher.”

“Why don’t we ever go see any of our relatives, Daddy?”

“Well, they live a long ways away, and besides I haven’t always gotten along with all of them. Not something I’m proud of. I’ve always wanted to go back and make it up to them. Family is very important, and I’ve cheated you kids out of knowing your aunts and uncles.”

The two pocketed their revolvers, put on their gloves, and trudged back over the icy wheat stubble. As they made their way home, they heard the lonely wail of a train whistle. Joy glanced west, where the rails ran, and spotted the plume of smoke. A fervent longing to travel swept over her, as it frequently did. The freight train was headed south, and her heart was in the South. “Daddy, do you think we’ll ever go back to Virginia?”

Winslow did not answer, merely shaking his head. When Joy saw that he could not speak, she felt his sadness. She was twelve when they left the hills of Virginia to come to North Dakota, and she still longed and dreamed for those hills and the warm summers of the southland.

When they arrived at the house, Joy said, “I’ve got to go milk the cows, Daddy.”

“All right, but we’ll be leaving pretty soon, so don’t dawdle.”

“I won’t.”

Joy ran into the barn, where she took off her gloves and heavy coat, leaving on the two flannel shirts she wore for extra

warmth. She noted that the cow’s breath rose like steam in the cold air.

“All right, Sookey, I’m coming.” Grabbing a three-legged stool and a bucket, Joy sat down, leaned her cheek against Sookey’s silken flank, and grasped two of the cow’s teats. The milk made a steady tattoo in the bottom of the tin pail, a rhythmic sound that Joy found soothing. Milking was one of her favorite chores. When she finished, she slapped the cow’s side, saying, “Now, that’s a good Sookey.”

She was turning to pick up her coat when her brother, Travis, stepped inside. He was two years older than Joy, a tall, lathe-shaped young man with the same cobalt blue eyes as his sister. His tawny hair fell down over his brow as he pulled his cap off and said with a quick grin, “Better get your best dress on today, sis. Charlie Thompson will be waiting for you. You know how sweet he is on you.”

“He is not either!”

“Sure he is. I saw him trying to give you a kiss after church last Sunday.”

Joy’s face flushed crimson, and she threw herself at her brother. Caught off balance, he went down, but he was laughing as she attempted to beat at him with her fists. He pinioned them, rolled over, and held her down tightly. “Don’t be mad, sis. You can do better than old Charlie. Come on now.” He rose quickly and helped her up. Dusting off the seat of his overalls, he said, “We’re going to eat at the Royal Café tonight.”

“Yes, and Dad said we could go to a movie. I hope it’s Charlie Chaplin.”

“I don’t. I hope it’s Buster Keaton. It probably won’t be either one, though, but anything’s better than nothing.”

****

“You about ready, Elaine?” Bill finished combing his hair and glanced over to where his wife was buttoning her dress. “Here, let me help you with that.” He fumbled with the

buttons in the back and then reached around and hugged her. “I remember the first time I ever helped you button up your dress. It was on our honeymoon. No, wait—I think I remember

unbuttoning

you.”

“Well, I should think it was on our honeymoon and not before!” Elaine turned around and patted his cheek. She was a small blond woman with the same cobalt blue eyes she had passed on to two of their three children. She looked tired, for the work on a wheat farm was not easy. She never complained, however, and now she said, “I’m glad you’re taking us all out, Bill. Everyone needs to be cheered up.”

Bill chewed his lip, then shook his head. “The drought this year was bad. We haven’t made any money at all. As a matter of fact, we’ve lost money.”

Shooting a quick glance at her husband, Elaine abruptly said, “We should never have left Virginia. It was my fault.”

“No more than mine. We made the decision together.”

“No, I thought it would be better. We weren’t getting anywhere there on the farm, and Opal made this sound like such a good way to get ahead.”

Both of them thought of how they had left Virginia at the encouragement of Elaine’s sister, Opal. She and Elaine had always been close, and when Opal married Albert Tatum and moved to North Dakota, the pair had missed each other. Opal had persuaded Elaine and Bill to buy a farm next to theirs. She and Albert had painted a rosy picture, but the move had proved to be more difficult than they could have imagined. The bitter cold winters had been followed with blistering summer heat. During their first two years there, drought had baked the land, and farmers all over the area had suffered dreadfully. All were praying that 1926 would bring them abundant crops and freedom from drought.