The Fiery Trial (30 page)

Abe Lincoln’s Last Card,

a cartoon in the English magazine

Punch,

depicts the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation as the last card of a desperate gambler. (Chicago Historical Museum, ICHi-22094)

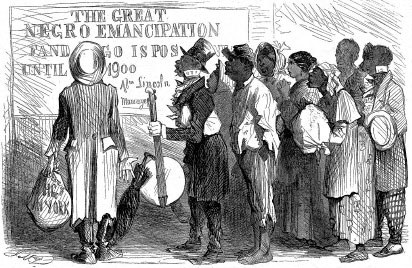

Despite the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which promised to free slaves in the Confederacy on January 1, 1863, Lincoln’s annual message to Congress of December 1862 proposed a plan of gradual emancipation that would not be completed until 1900. The caption of this cartoon reads: “Sensation among ‘Our Colored Brethren’ on ascertaining that the Grand Performance to which they had been invited on New Year’s Day,

was unavoidably postponed to the year 1900

!”

(Harper’s Weekly,

December 20, 1862, provided courtesy HarpWeek, LLC.)

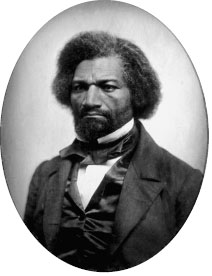

Frederick Douglass in an 1856 photograph. The great black abolitionist and editor met three times with Lincoln during the war. (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, NY.)

Alexander Crummell, a prominent pan-Africanist, discussed black emigration to Africa with Lincoln in April 1862. (Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

Martin R. Delany, an abolitionist whom Lincoln called “this most extraordinary and intelligent black man.” Delany visited the White House early in 1865 and became the army’s first black commissioned officer. (Ohio Historical Society)

William H. Johnson accompanied Lincoln from Springfield to Washington as his valet. When Johnson, an African-American, died in 1864, Lincoln arranged for him to be buried at Arlington Cemetery and chose the one-word inscription, a direct refutation of the

Dred Scott

decision. (Courtesy Anne Cady)

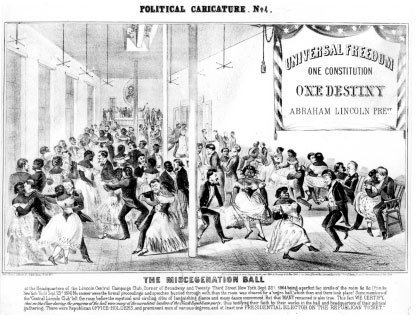

The Miscegenation Ball,

a Democratic campaign lithograph from 1864 that depicts white men dancing with black women at the “Lincoln Central Campaign Club,” supposedly at a ball celebrating the second anniversary of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Two reporters for the

New York World

invented the word “miscegenation” as part of a plan to associate Republicans with “social equality” between the races. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

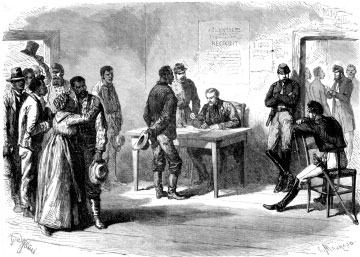

Negro Volunteers Enrolling in Gen. Grant’s Army Corps,

an engraving from the French periodical

Le Monde Illustré

in 1863. The service of black soldiers strongly affected Lincoln’s evolving ideas about the role of blacks in postwar American life. (Chicago History Museum, ICHi-22053)

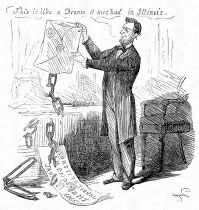

Uncle Abe’s Valentine Sent by Columbia

shows Lincoln opening a Valentine’s Day envelope, out of which spills the Thirteenth Amendment and broken chains. The House of Representatives had approved the amendment, which abolished slavery throughout the United States, on January 31, 1865. (Provided courtesy HarpWeek, LLC.)

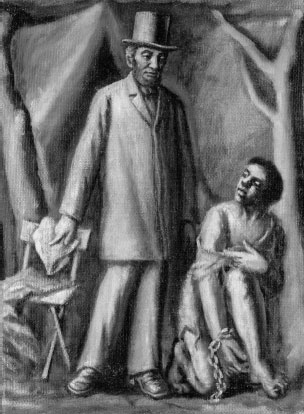

Lincoln and the Female Slave,

an 1863 painting by David B. Bowser, a black artist living in Philadelphia, depicts Lincoln conferring freedom on a kneeling slave. It offers an early example of the apotheosis of Lincoln, among both black and white Americans, as the Great Emancipator. (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY)

By the end of July, over 850 blacks had escaped to Fortress Monroe. “Are these men, women, and children slaves?” Butler wondered. “Are they free?” For the moment, no answer was forthcoming. “

Where

we are drifting, I cannot see,” the abolitionist Lydia Maria Child would write a few months later, “but we are drifting

some

where; and our fate, whatever it may be, is bound up with these…‘contrabands.’”

12

I

F

OR NEARLY THREE MONTHS

after the firing on Fort Sumter, Lincoln and the executive branch, in effect, were the national government. But once Congress assembled for the special session Lincoln called to begin on July 4, 1861, he had to share power with other politicians, many of whom had far more experience in national affairs than he and thought of themselves as equally attuned to northern public sentiment and the interests of the nation, and equally qualified to judge military and political strategy. Thanks to the departure of the seceded states, Republicans now held substantial majorities in both houses. Throughout his presidency, Lincoln strove to forge as close a working relationship with congressional Republicans as possible. Generally, he ceded economic matters to the lawmakers, while attempting to retain control over the issues he believed fell within the rubric of presidential power—especially the conduct of the war. Eventually, he became convinced that he, not Congress, possessed authority over the slavery question. Yet Congress persistently tried to shape national policy regarding slavery. The special session of the Thirty-seventh Congress was no exception.