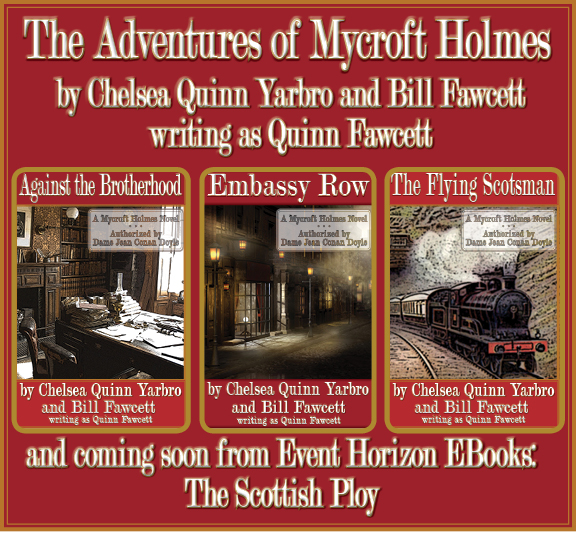

The Flying Scotsman (34 page)

Read The Flying Scotsman Online

Authors: Chelsea Quinn Yarbro,Bill Fawcett

Tags: #Holmes, #Mystery, #plot, #murder, #intrigue, #spy, #assassin, #steam locomotive, #Victorian, #Yarbro

“What is it, Guthrie?” asked Holmes, who had been watching me.

With a sinking feeling I opened the portfolio, searching for the pencil box and Sutton’s sketches, and found instead two files with Golden Lodge seals upon them. I held them as if I expected them to burst into fire. I could not think of what I could say to Sutton to apologize for the loss of his drawings.

Holmes was sitting a bit straighter; he took the files from me and very carefully opened the first, his heavy brows rising sharply. “Dear me. I hope she does not get into trouble for this.” He turned appreciatively to the second page.

“Who?” I was still holding the portfolio in bewilderment; my thoughts would not budge from the three letters—very nearly correct, but slightly dissimilar from mine.

“Why, your Miss Guthrie. Miss Penelope Evangeline Gatspy,” he said, indicating the letters, “Mr. Paterson Erskine Guthrie.” He cracked a laugh. “She’s very fond of you to do this.”

Finally my interest stirred. “What is it?”

“These are copies of the Golden Lodge files of Brotherhood assassins, with records of their activities for the last five years.” He achieved a tired smile. “I hope she likes the sketches.”

The lethargy that had held me finally vanished. “She did this deliberately,” I said, intending it as a question, but realizing, as I spoke, that she had switched our portfolios when she had sneaked into my compartment to hide from Loki.

“That she did,” Holmes approved as the first shrill whistle announced the arrival of the police. “She’s a most capable girl, your Miss Gatspy.”

For once I did not protest this designation; I felt my bruised face crease into smiles. “Yes, she is, isn’t she?”

FROM THE PERSONAL JOURNAL OF PHILIP TYERS

They are in Edinburgh, safe, and the HHPO is in the care of the Navy. Now Sutton and I can retire for what remains of the night. There is much to do in the morning, and I must make myself ready to finish my tasks.

THE LONG

beams of

late afternoon sun glowed in the windows in the elegantly rose-and-cream-appointed Day Room near the entrance to the Royal Scots Club, across from the dark wood of the club’s pub. To my left, windows opened onto a tree-filled park, and in the distance I could see uphill to the Princes Road, which was becoming a commercial alternative to the shops of the High Street.

We had just been talking with a neatly uniformed Major about the Holybrooke conspiracy, a hidden tunnel, tossing someone off a folly, and meeting with the Queen of Ireland at a mythically named Lyonesse Cottage. From Mycroft Holmes’ questions it appeared that this was something that had occurred before my tenure and had happened while some part of the Royal Scots Regiment had been stationed in Ireland for an extended period. It appears that quick action had prevented an insurrection. From the rather ominous end to the conversation, it was apparent that the matter had never been resolved. When I began to ask about the event after the officer had limped painfully across to the pub, my employer changed the subject.

Mycroft Holmes sat in a high-back, overstuffed leather chair with studded arms and back, facing the butler’s table where our tea was laid out. A folded newspaper nestled beside the teapot. “You’ve seen that, I suppose?”

“Swedish Prince Saved by Scottish Knight?” I quoted. “Oh, yes. It was waiting for me after I bathed this morning. Sir Cameron is making all he can of it. Always one to crow on any dungheap he can find.” I was unwilling to modify my tone of contempt.

“Let him, dear boy, let him. So long as the world thinks Cameron MacMillian is a hero, they will not bother to inquire into our affairs, which suits my purposes very well—and Miss Gatspy’s,” he added for emphasis.

“Oh, yes, I understand that. But to have a fool like Sir Cameron feted and praised, I find it hard to bear.” I looked down at my skinned knuckles and the rich purple-and-red coloration around the abrasions.

“I do understand your sentiments on this occasion, but I do not share them.” He leaned forward and looked speculatively into the pot, replacing the lid with care. “I’ll be Mother, if it’s all the same to you.”

“Just as you please, sir,” I said, feeling a bit ashamed that I had been so restful today and he had been active. “I am sorry I haven’t put myself at your disposal earlier.”

Something of my feelings must have shown themselves on my countenance among the bruises, for Mycroft Holmes said, “So conscience stricken, Guthrie. Why?” He had poured tea into a cup for me.

I shrugged. “I should have been more observant,” I said, not wanting to recite the litany of failures I had rehearsed in my thoughts since shortly before sunrise whenever I wakened from my turbulent sleep. “Who knows what we might have been spared had I been more diligent.”

“My dear Guthrie, so should I,” Holmes said as he poured his own tea. “But consider the whole of our mission and tell me honestly you anticipated half of what we encountered in our efforts to see Prince Oscar to safety. In my nearly fifty-six years I don’t think I have seen so many kinds of deceptions packed into a single mission as has been the case with this one.” He held out the telegrams he had received that day. “First is the news that Prince Oscar sailed with the morning tide, and no mishaps have overtaken him on the maritime leg of his journey home.” He laid that telegram aside. “Well, go on, drink your tea. No sense in letting it get cold.”

I looked about, noticing we were alone. “Do none of the other members take their tea here?” I picked up the cup-and-saucer, noticing the tea was Chinese black.

“Of course. But the senior members have very kindly allocated this room for my use while we are here.” He looked directly at me. “Most of them do not know the particulars of my work, nor do they wish to.”

“No doubt a wise decision,” I said, and tasted the tea before deciding to add a little sugar to it.

“I have been reading over the files Miss Gatspy left; most illuminating, but also profoundly disquieting. I thought we had superior records at the Admiralty, but I discover we are laggards in this arena. You will want to have a look at these when we take the train home tomorrow. They help you while away the hours between Edinburgh and London. For,” he went on with an arch smile, “I fear we cannot expect another murder, nor an assassin—let alone two—to liven our journey.”

“I shall contrive not to be bored, sir,” I responded in the same tone.

Holmes added sugar and milk to his tea, then held up the second telegram. “I fear there is no sign of Chief Inspector Somerford yet. Had I not had confirmation that Missus Spencer was once Miss Vickers, I would not be as concerned as I am, nor would we have been exposed to half the dangers we were. During our journey home, we will have to settle upon some means to root out the corruption that has resulted from that unfortunate liaison. I also have some additional information regarding this lamentable state of affairs provided by Tschersky, which I intend to factor into my deliberations. Do not worry yourself unduly on the matter today.”

I drank a little of my tea. “Do you think the Admiralty will want to become entangled with trouble within the police?” It had been bothering me since I slipped into the bath.

“Once I show them how that corruption has tainted our mission, I think they will understand that they must take action for the sake of their own men in the field.” He held up another telegram. “Tyers has done his part, and I must say Sutton has acquitted himself admirably.”

“That does not surprise me,” I said.

“Nor does it surprise me, but I am still pleased to learn of it,” said Holmes, becoming a bit more expansive. “You know, dear boy, I have come to feel very real gratitude toward Inspector Carew, to say nothing of the unfortunate Mister Jardine and the rest of them. I am even, in retrospect, pleased that Mister Burley rode with us as far as he did, hoping to improve the story he would file.” He smiled at me, waiting for my response.

I knew he expected me to ask him to explain, and I was curious, so I obliged. “Very well—why this unexpected appreciation for so ... disruptive an episode?”

Mycroft Holmes fixed his eyes on the far wall, the better to concentrate on what he was about to say. “I spent a good portion of the morning thinking this over. Loki—assuming that Whitfield is half of Loki—had a schedule that the murder disrupted. Loki had been counting on the train being on time. As it was, because of all the delays, he had to hide on the train instead of simply leaving when his shift—and his dirty work—was done.”

“He told me he’d worked for the railroad for years,” I said, still shamed at how readily I had accepted what he had told me as true. “It was all so plausible.”

“And so it should be. Think of it, Guthrie. He is made late by a murder, so he is surrounded by police and passengers who are distressed by the deaths and the delays. He finds himself under scrutiny. He cannot proceed as he intended, and so he is forced to settle for an improvisation that proves to be disastrous for him.” His steady gaze returned to me. “Between the delays and Jasper Carew, Whitfield was not able to strike when and how he intended, and for that I will be grateful to Messieurs Jardine, Dunmuir, and Heath. Prince Oscar may owe his life to them. And, of course, to Miss Gatspy.”

I felt my pulse jump at her name. “You do not call her mine,” I said as lightly as I could.

“I am not one to state the obvious.” His austere expression gave way to one less condemning. “You have every reason to be proud of her, Guthrie.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, nodding once as I drank rather more of my tea than I had intended.

“And,” Mycroft Holmes went on in studied casualness, “there was a note sent around about noon. I think you will be glad to have it.” He handed a small envelope to me with my name scrawled on it. “A constable brought this; he said it was dropped off at his station by a fair young woman in mourning-clothes.”

I took the envelope, staring down at the elegant, curving hand that had written my name, making the initials particularly large. “Do you mind, sir?” I asked, knowing it was rude to read what I assumed was a private note in front of him.

“Of course not. Go on.” He leaned back in his chair and gave himself to the perusal of a fresh-baked scone.

The note was on good linen stock but without a trace of an address. It was quite brief.

Dear P. E. G.

I believe each of us has something that belongs to the other. Perhaps we should effect an exchange on some date convenient to us both, what do you think?

Until then, take care of what is mine, as I shall what is yours,

Yr most devoted,

P. E. G.

I read it over several times, though the words remained unchanged, cryptic and liable to many interpretations. “How like her,” I said at last, as I refolded the note and put it back in the envelope and placed it in my waistcoat pocket, over my heart, chiding myself for this sentimental gesture even as I made it.

Mycroft Holmes had been watching me from under his heavy brows. “No wish to intrude, dear boy, but it strikes me that Miss Gatspy’s not a woman whose affections are given lightly.”

“Just as well,” I responded. “I am not one to bestow mine lightly.” “I am aware of that,” Holmes said, and added, “You and she may not always stand on the same side, as I am sure you are aware.” He poured more tea into my cup. “I do not intend to discourage you, but I hope you will not place yourself in an untenable position because your affections are engaged.”

“I share that hope,” I said with feeling. “And I am certain she does, too.”

Holmes leaned back in his chair. “Most assuredly, Guthrie; most assuredly.” He glanced at the files she had provided. “We have proof of that in our hands.”

Immediately he said this, my heart jumped. “Yes, we do, don’t we?” Many of the obstacles I had seen strewn in any path that might bring Miss Gatspy and me together seemed now to be less formidable.

But Mycroft Holmes did not answer my smile. “I think we may also consider ourselves warned that the world has grown more dangerous than ever we thought it was. Our enemies are many and their designs are far more nefarious than we realized. But at least we are no longer ignorant. These files have made it possible for us to buy some time.” He lifted his teacup in ironic toast to the files; I mirrored his action, endorsing his conviction. “We have an obligation to make the most of it.”