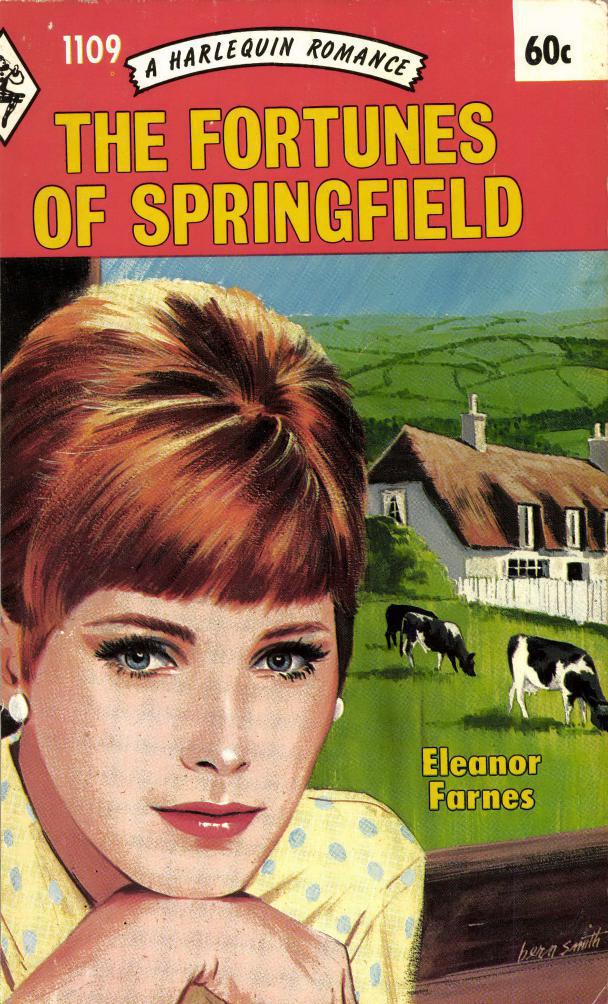

The Fortunes of Springfield

Read The Fortunes of Springfield Online

Authors: Eleanor Farnes

THE FORTUNES OF SPRINGFIELD

Eleanor Farnes

D

avid Springfield of Springfield was ready to take on the tough job of pulling together the family's neglected estate. But to look after his brother's three orphaned

(and rather unmanageable) children as well would, he felt, be beyond him. So he was delighted when pretty, competent Caroline came on the scene as housekeeper.

CHAPTER ONE

DAVID SPRINGFIELD engaged the single taxi that was waiting at the station, and, with the help of the driver and a porter, loaded his considerable amount of luggage on to it. Then, asking the driver to pick him up in the market square in a quarter of an hour, he

ma

de

off with a long, brisk stride through the February

afternoon.

He wanted a little leisure to look at the town again. It was fifteen years since he had seen it, and it seemed to have shrunk but to have retained all its beauty. He

cam

e

out of the station road on to the main street—a very wide street with grass verges and some fine old trees, yet still room for pavements to accommodate the many shoppers, and a road in which cars could be

parked as well as driven.

Most of the old shops were still there, some with their rounded bay windows, but some putting

a

modern face on their old red brick forms. The roof lines wore still as jumbled and as beautiful as he had remembered them all these years, their tiles weathered to all shades of red

and

brown, here and there yellowed with lichen.

David walked along, picking out familiar landmarks, until he came to the market square, now almost deserted. The winter afternoon was short, and already yellow lights twinkled from the shops and the houses. If he wanted to reach the farm in daylight, he had better find his taxi and hurry along. He looked round to find the driver waving to him across the square and he went across and seated himself in the vehicle, which was certainly a new once since his day.

As he looked out at the familiar roads and lanes, picking out landmarks here, noticing new developments there,

h

is thoughts went ahead to Sp

ri

ngfield,

where he had been

born

and brought up; and which he had left at the age of eighteen because it was obvious to him, even at that early period of his life, that he would never be able to work with his brother. They had never got on

wel

l together, and Gerald had always been determined to keep Springfield in his own hands: and now Gerald was dead, and, according to the letters that David had received, his affairs were in a dismal muddle.

David thought of those letters. The first was from the family: solicitor, informing him of Gerald’s death; the second, also from the solicitor, had given him a comprehensive picture of the financial affairs of his brother and of the farm. It was not a pretty picture. David wondered how his brother had avoided bankruptcy. He had begun to think then that he must return to England to sort things out; and then had come the letter from somebody signing himself Duncan Wescott, which firmly decided him. For West

c

ott’s letter had not only painted an unprepossessing picture of the farm; it had also shown David to what extent three children were neglected, and how much they needed care.

Wescott was new to the neighbourhood since David had lived there, but his letter sounded sincere and genuine; and with what he had written well in

mind,

David looked about him with keen dark eyes,

missing

very little.

It did not escape him, as they approached Springfield Farm, that many of the hedges were broken, many of the gates down, fields given to poor pasture that should have been ploughed, the drive gr

o

wing a good crop of weeds. But it was certainly a shock when he looked on the house for the first time for fifteen years. A stranger might almost have thought it derelict.

David had a very strong affection for the family house; the house that had been in his family

si

nce

it was built in 1760, where

h

is happy youth had been spent, and which, in all his years in New Zealand, had spelt home for him. As he looked at it now, he felt a

grim

contempt for the brother who had allowed it to reach its present state. It certainly had not seen paint for years, the gutters were broken in several places, the creeper had grown over the roof, several shutters hung by one binge, the whole place had a neglected and shabby air. “But its bones are good,” thought David suddenly, feeling a great resolve grow in him. The structure looked sound (though he had still to examine it). He would bring it back to its former beauty.

The driver unloaded the luggage on to the doorstep. David helped him, paid him off, and rang the bell of the house. There was no reply, and he suspected,

rig

htly,

that the bell did not ring. He knocked loudly, but still without success. He tried the handle and the door opened, so he went into the long hall and looked about him.

Here was a further shock. No brightly-polished, shining house was here, but a neglected, shabby, unloved one. Mo

rn

ing-room on his right and dining-room on his left, with no light shining under the doors, no sound

co

ming

from them. But plenty of sound from along the passage that led to the kitchen quarters; a sustained yelling from a small child, a shrewish voice raised in shrill scolding, and other childish voices interrupting. David, still

grim,

still shocked at what he had seen, went along to the kitchen door and knocked loudly on it.

Instantly, everything inside the room was quiet. He turned the handle of the door, pushed it open, and stood in the doorway, and four startled faces looked up

at him.

David took in the scene, slowly, missing little. The four were gathered round the kitchen table, having tea. The whole kitchen was incredibly untidy and dirty, the cloth covering the table was stained with the telltale marks of many meals, there was a pile of unwashed crockery in the sink, muddy footmarks all over the floor became concentrated by the door leading from the scullery. He noticed that the children themselves were quite well dressed, but they were untidy, while the woman seated behind the big brown teapot, wear

ing

a crumpled blue overall, looked as if she had long ceased to bother about herself. She now faced David truculently.

“What

do you want?” she asked. “Isn’t it usual to knock on doors? Who gave you the right to walk in?”

“I knocked loudly on the door,” said David, “but there

w

as too much noise for you to hear me. And I have a right to walk into my old home, I

thin

k. I’m

these children’s Uncle.”

“Well, you might have given me some notice,” she grumbled. “With all I’ve got to do here, I don’t call it fair to walk in unannounced.”

“I wrote to the solicitor and told him I was coming.”

“

Well,

he

doesn’t put his face in here more

than

he

has to

. It’s

about time somebody came to look after things.”

“Just what I was thinking,” said David. The woman gave him a sharp look, but did

n

ot reply. David went to the table where the three children watched him carefully and silently.

“You are Terence, aren’t you?” he said to t

h

e boy, and held out his hand. The boy ignored the hand. He said:

“Yes, I’m Terry.”

“And your sisters

—let me see—Wendy and

Barbara

Which is which?”

“I’m Wendy,” said a little girl of six. She had a sweet smile for him, and a mellifluous little voice. “This

is Barbara, only we always call her Babs.”

“And it was Babs making all the noise, was it? Well, I’m your Uncle David, and I’m coming to live here with you.”

They received this news in silence. David decided he would need time to improve an acquaintance begun under such adverse conditions, and turned back to Miss Church. She was still disgrunt

l

ed because she had had no notice of the visit, but she supposed she could fix a room up for him. He had better have his brother s room—it was the farthest from the children’s rooms, and he might get a bit of peace there. She could make fresh tea for

him

if he wanted it, but what was

in

the pot was cold now.

David refused this ungracious offer, and, having found out that Miss Church did not bother about supper for herself, but had some sort of snack when the children were in bed, and that the Green Lion still did meals half a mile away from the house, went off to carry his luggage to his room, determined to have his supper at the Green Lion.

The sorry story begun where the taxi joined the Springfield property, and, in the house itself, was continued upstairs. Everywhere, evidence of neglect and indifference. How could Gerald have allowed all this to happen? Could the death of his wife Joy, when Barbara was born, have had a good deal to do with it? Had he gone to pieces then, or was it before then? He had always been, in David’s estimation, a weak character; but he had been left a flourishing farm in good order. It should not have been such a difficult task to keep it running. But, however it had come to pass, things were now in a p

e

r

i

lous state; and David felt a challenge in this aspect of

his

old home.

Next morning, he was the first person awake and out of bed. There had been a sharp frost in the night, and he looked out upon a world where every branch and twig and every blade of grass was white with frost. He

went downstairs, and finding no fires anywhere,

l

it one in the kitchen, and put water to boil in the electric kettle. Miss Church had apparently made hasty efforts to tidy the r

o

om while he had been at the Green Lion; for the sink was empty of dishes, the floor had been swept, and a lot of the rubbish that had been lying about had been gathered up and put away. He made some tea, and was searching for cups and saucers when she came into the room. She had made an effort to tidy herself too, and wore a clean overall.

David poured out the tea, and she took a cup gratefully. He asked her who was working on the farm, and learned that there were two farm hands living on the farm in semi-detached cottages. He knew the cottages well. He would go out and find the men. One was

milking

, the other was cleaning the

milk

utensils in the dairy. Here, as everywhere else, David’s sense of the fitness of things was offended. The men had let things go. Things were going to be different now. They would work, or they would go. Later on, he would let them know this, but for the moment, while he was settling in, they could carry on.

One thing was certain. Miss Church must go. And, until he could find a good housekeeper, somebody must help temporarily. He asked the farm hands where temporary help might be found, and one of them said his wife might do it, if that M

i

ss Church was out of the way. Nobody could get on with her. And the children were a handful too. But still, she might do it to oblige.

He would ask her.

Mrs. Davis did do it to oblige. She waited until the slovenly Miss Church went, embittered and protesting, yet swearing that nothing would make her stay in a house where she had always been so badly treated. Then she came daily, in time to get the children’s breakfast, and stayed until they had been put to bed, cooking her husband’s meals at the house. She straightened

the house up a little, but, as she said to David, it really needed a good spring-clean from top to bottom.

In the wide street of the town, with its bustling air of prosperity and busyness, there were many gracious houses, for most of the town had been built long ago, in an elegant period: and one of the most gracious, and also one of the largest, was Mrs. Webster’s. In this house there had also been a recent death, but there was nothing tragic about this one, since Mrs. Webster had been seventy-eight and had lived a good and full life. And now the relatives had been and gone, the houseful of beautiful furniture had been divided amongst them, the house had been sold, and Annie and Caroline walked through its emptiness for the last time.

Annie and Caroline had looked after Mrs. Webster. For many, many years, it had been Annie and Hilda: but then Hilda had found her rheumatism too much for her and had retired into a little cottage, and Caroline had been found to take her place. So that while

Annie

had been with Mrs. Webster for over thirty years, Caroline could claim only seven. For Annie was now seventy, while Caroline was twenty-three; Annie was finding all work a bit difficult, and was looking forward to joining Hilda in retirement, while Caroline worked with will and vigour and was looking forward to a change in her life; Annie was wrinkled and grey, and Caroline was upright, clear-skinned, intelligent and eager.

Everybody in the town knew them. They knew that Annie had been for thirty years with

Mrs. Webster and would now join Hilda in the cottage. They knew that Caroline, at sixteen,

had been brought from some home or orphanage where she had been brought up, to help

Annie when Hilda left. They had seen her change from a shy girl of sixteen to a competent

young woman of twenty-three with charming, natural manners, going about the main street of

the town on Mrs. Webster’s commissions; driving Mrs. Webster about in the old but reliable

Daimler; cutting flowers for the house under the old lady’s direction. They all knew that

Caroline had become a companion and friend to her employer in recent years, and they all

wondered now what she would do.

With them through the house went Mrs. Fuller, Mrs. Webster’s daughter, looking her last upon these spacious rooms before returning to her home in Cornwall. She also wondered what Caroline would do, and knowing what a great help she had been to her mother, Mrs. Fuller said:

“You know, Caroline, you can always come to us in Cornwall, if you cared to take on the job of housekeeper.”

“That is very kind of you, Mrs. Fuller, but I haven’t quite made up my mind yet what I will do.”

“Or if you want a little holiday before finding another job, you are welcome to our spare room.”

“Thank you very much. May I let you know later? I do appreciate such a kind offer.”

But Caroline had no intention of going to Cornwall, either for a short holiday or to work there. She wanted to break away from the Webster family completely. Many ideas mulled about in her brain, and she wanted quiet and time enough to think about them carefully. To be able to do this, she had taken a room at The Hollies guest house for a short time, and she would go to it when this last tour of inspection of the old house was finished.

“It’s sad, in a way,” said Mrs. Fuller, “to

think

of the old place going to strangers. It has been in the family so long. But there, it’s too big for most people these days.”

Annie, who was in a very sentimental and reminiscent mood, began to talk of the old days with Mrs. Fuller, and Caroline, her mind occupied now with the future rather than the past, waited impatiently until she could take her leave of them (promising to call and see

Anni

e

in her cottage, promising to write her news to Mrs. Fuller), and get away to her room at The Hollies and review her position.

This was not at all bad and she recognized the fact Mrs. Webster had left her a little legacy that would be put away for a rainy day, but could be dipped into to provide for this short respite. Caroline knew that she was adept at running a house. She had learned to type for Mrs. Webster. She had certainly, under Mrs. Webster’s helpful guidance, furthered her education; and recently she had become more and more of a companion and friend to the old lady, and had mixed more and more with her friends. She did not doubt that she would soon find work, as several prominent townspeople had promised to look about for her, but she was not sure that she wanted to continue to work in this town, much as she loved and admired it.

She had worked for a long time with old people. Mrs. Webster, charming as she was, was old. Annie had been preoccupied for some time with her own poor feet, Hilda’s rheumatism, Mrs. Webster’s neuralgia. Most of the visitors were Mrs. Webster’s contemporaries. Caroline felt that she wanted a change.

She had a great hankering to go abroad. She had made one wonderful tour with Mrs. Webster, and this glimpse of glories, previously only imagined, had fired her with a desire to go again. That tour had been a happy accident. Mrs. Fuller should have gone with her mother, and all the tickets had been obtained, all the reservations made, when one of the Fuller children had gone down with measles, and Mrs. Fuller decided not to go, so that Caroline had taken her place. Now she wondered if it

might

be possible to work abroad, and which of the people of the town mi

ght

be able to help her.

In her room at The Hollies, with no work to occupy her, a certain loneliness threatened her. She knew from past experience that it was much better to fi

ght

it at the outset, or to refuse, if possible, to acknowledge it at all. Mrs. Webster had had grandsons and granddaughters who-sometimes came to stay with her, and were immediately included in all the social affairs of the town. Many of them were about Caroline’s age, and they filled the big old house

w

ith gaiety and laughter. The girls brought with them their beautiful clothes, day dresses, evening dresses, tennis outfits, casual sweaters and slacks, expensive nightwear. They were pretty and confident, and the young men were casual, handsome and equally confident. They took their place in the sun for granted, and it did not occur to them that Caroline might watch them wistfully when they went off, piled in sports cars, to the houses of

fri

ends. Youth, gaiety, young love

...

Caroline had stayed behind with Mrs. Webster and old Annie, but her thoughts had often gone after the young people, wondering what they did, what they said to each other, what happened at the dances, the tennis parties, the picnics.