The Friar of Carcassonne

The Friar of Carcassonne

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Back to the Front

The Perfect Heresy

Sea of Faith

The Friar of

Â

Carcassonne

R

EVOLT

A

GAINST THE

I

NQUISITION

IN THE

L

AST

D

AYS OF THE

C

ATHARS

STEPHEN O'SHEA

Copyright © 2011 by Stephen O'Shea

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Douglas & McIntyre

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver

BC

Canada

V

5

T

4

S

7

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Published in the United States of America by

Walker Publishing Company, Inc.,

a Division of Bloomsbury Publishing

Published in the United Kingdom by Profile Books Limited

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN

978-1-55365-551-0 (cloth)

ISBN

978-1-55365-971-6 (ebook)

Design by Simon Sullivan

Jacket design by John Candell

Jacket illustration:

The Albigensian Inquisition

. The Agitator of Languedoc

Bernard Délicieux (1260â1318), a Franciscan Monk, during his trial, by Jean-Paul Laurens (1838â1921). © Scala/White Images/Art Resource,

NY

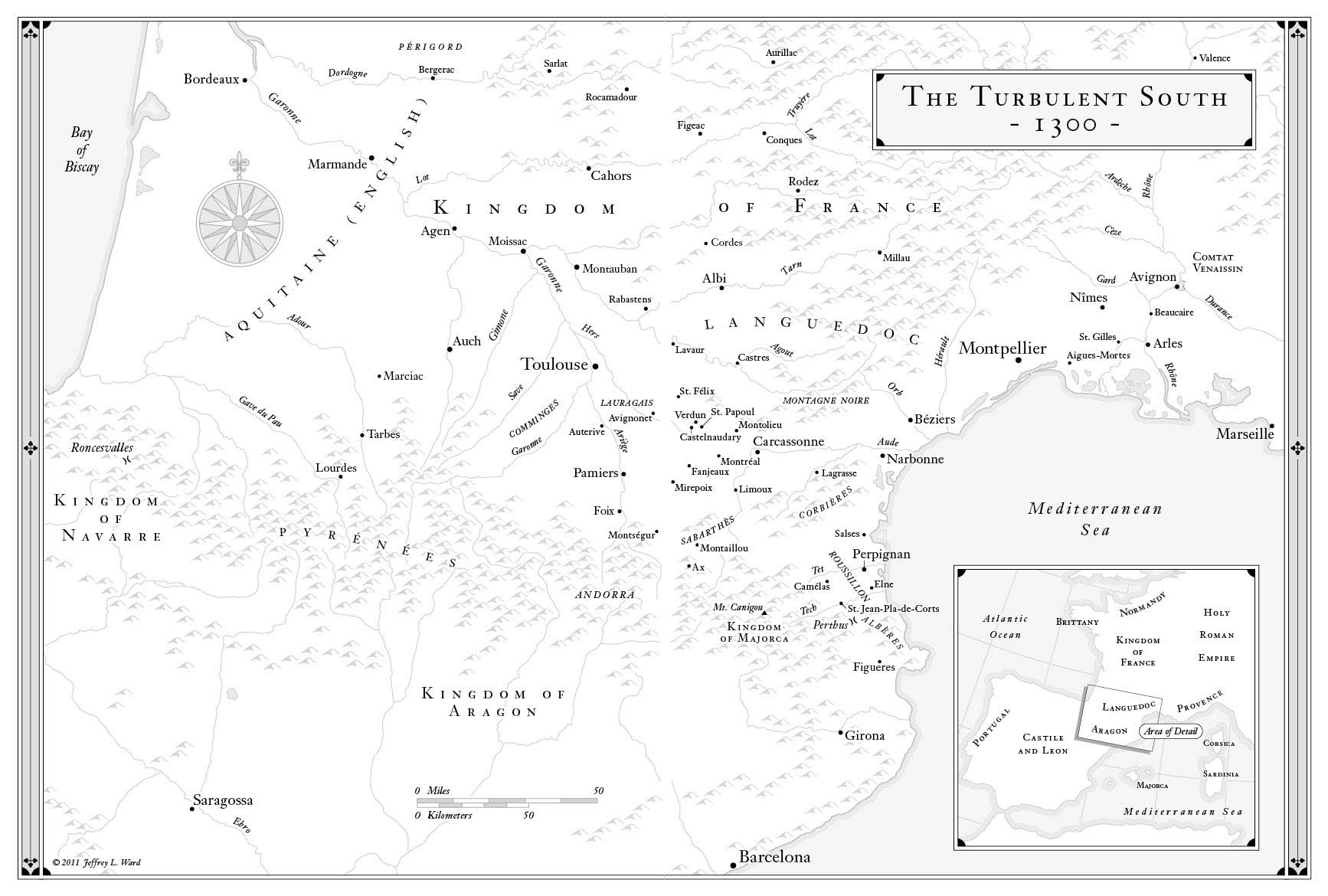

Maps by Jeffrey L. Ward

Douglas & McIntyre gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

To Kevin and Donal O'Shea,

brothers, not friars

CONTENTS

I. T

HE

W

ORLD OF

B

ERNARD

D

ÃLICIEUX

13. T

HE

I

NQUISITOR

G

IVES A

R

EADING

16. T

HE

K

ING AND

Q

UEEN IN

L

ANGUEDOC

19. C

ATHARS AND

S

PIRITUALS

, I

NQUISITORS AND

C

ONVENTUALS

R

EADERS FAMILIAR WITH THE PERIOD

will note immediately that the word

inquisition

appears throughout uncapitalized. The use of the uppercase

Inquisition

, common until recently even in scholarly studies, leaves the impression that there was a well-oiled, centralized bureaucracy supporting the inquisitors, whereas in the early centuries of inquisition this was not the case. The inquisition as an institution did not exist, only inquisitors in limited jurisdictions for limited time periods. However, the idea of an institution certainly existed and its ephemeral manifestation in these years was often referred to as the Holy Office, an uppercase usage retained in the text.

As for the vexed problem of names, I have made the usual stab at exception-riddled standardization that, I know from experience, falls short of being universally pleasing. As is customary, the names of monarchs and popes have been given in English. The exception is the king of Majorca, whose Catalan identity I wished to stress; thus Jaume, not James. The same stress on identity has led me to retain the Occitan names for the men of the south. The tension between the Occitan-speaking southerners of Languedoc and the French-speaking northerners of the Kingdom of France is central to the story. Using a historical figure's Occitan name locates his background and his allegiances. Thus, for example, Peire Autier, not Pierre Authier. However, for those southerners already widely known by their Gallicized namesâBernard Saisset, Pierre Jean Olivi, and Guillaume de Nogaret, for exampleâI have retained the French so that readers who know something of these figures will not think they are reading about someone else.

Complicating matters is the problem that much of my research involved French-language material, whose authors almost always use French names for everyone in history. Where an obscure Occitan figure appears only in French, I have not attempted the foolhardy task of reconstituting his name in his mother tongue. But I hope enough of the Occitan-French divide is left standing to shape the reader's view of Bernard Délicieux's Languedoc.

As for the names themselves, I am acutely aware of their unfamiliarity and sheer number. Having been chided for a phone-book-like embarrassment of names in a previous work, I have tried to trim as many distracting names from the narrative as possible. Thus, unimportant figures who crop up but once or twice in the narrative are identified by name in the notes, not in the main text.

A friend, after having finished reading my earlier work on the Cathars,

The Perfect Heresy

, exclaimed to me: “I get it! Everyone in the first half of the book is called Raymond, and everyone in the second half is called Bernard!” As this present work deals with the latter half of the Cathar story, there are indeed a lot of Bernards. I have taken special care to keep them from bumping into each other, but the reader will have to be the judge of whether I succeeded.

Figures of exceptional importance in the story of Bernard Délicieux are

marked with an asterisk.