The Gathering (44 page)

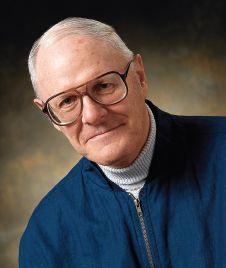

Authors: William X. Kienzle

Tags: #Crime, #Fiction, #Mystery, #Suspense, #Thriller

Manny, and even Mike, were moved by this simple revelation.

“And I gave him such a hard time,” Manny said.

“We all did at one time or another, in one way or another,” Alice said.

“Long before Pope John called for a reform of Church law,” said Koesler, “Stan believed that Canon Law was just an effective way of keeping people in line. If he had become what he wanted to be—a good secretary—he wouldn’t ever have thought about Canon law. Now he had to enforce it in its most literal and exact demands.

“The final blow was his status. He insisted that I tell him what his situation really was. I told him, of course, that his illegitimacy was an impediment that could be dealt with … that it was no great problem.”

“How come he didn’t know that himself?” Rose asked.

“He explained it that night,” Koesler said. “He was like someone who feared he had cancer and was too frightened to go to a doctor and find out for sure. Too frightened that the doctor would confirm his worst fears.

“I can’t tell you how relieved Stan was when I told him that the impediment didn’t really make that much difference.”

“And then you told him, didn’t you?” Mike said. It was an accusation rather than a question.

“Told him what?” Alice asked.

“He just didn’t have an out, did he … they just didn’t leave him an out,” Mike said.

“That’s right,” Koesler replied. “He owed his priesthood to the very force that surrounded and engulfed him.”

“He wasn’t really a priest!” Manny’s tone was almost awed.

“That is, indeed, the bottom line,” Koesler said.

“When I think,” Rose said, “of the things we suffered—or thought we were suffering in our lives—!”

“They don’t seem much in comparison,” Alice said.

“Now,” Koesler said, “you know what the cause of Stan’s death was …”

“Officially, it’s listed as an accident,” Mike said.

“That’s right. Not wanting to throw my police weight around”—Koesler bowed to Mike—“I talked to the medical examiner. He found nothing to indicate anything other than accidental death. There was no suicide note. No sign of a struggle or anything you’d be likely to find in a case of homicide. Which leaves only accidental death.”

“After what we’ve heard,” Manny said, “I’d say it probably was suicide. But if so—and I never thought I’d say this—it was justifiable suicide.”

“I guess I was the last person to talk with him—before he let his life slip away,” Koesler said. “He was like a trapped and hopeless animal. He couldn’t have been responsible for what he did. I have to agree with Manny: justifiable suicide.”

“After all,” Mike added, “the Church nowadays considers that an apparent suicide was just that: apparent. The presumption is that the guy was not in full command of his faculties. I agree with Bob and Mike: justifiable suicide.”

“And I agree,” Alice said.

“And I too,” Rose said. “But something’s missing.”

“I can’t imagine what …” Alice said.

“I’m surprised”—a smile played at Rose’s lips—“with good Catholics like us, I’m surprised we haven’t come up with ‘who dun it.’”

“You mean who’s responsible?” Manny said. “My nominee has to be Simpson. He screwed everyone: Mr. and Mrs. Benson, and, of course, Stan. Just to get—if Mike is correct—a chance at a better parish.”

“I think,” Rose said, “maybe we all share a bit of the blame.”

Judging from the looks the others gave her, it was not a consensus.

But Koesler would not be bulldozed. He took a piece of paper from his pocket and unfolded it. “Indulge me as I read,” he said. “This is a column by Sally Jenkins of the

Washington Post.

It ran August 4, 2001. It impressed me so much that I’ve kept it. I think it speaks to our present situation.

“Anybody remember a pro football player named Korey Stringer?”

“He played for the Minnesota Vikings, didn’t he?” Manny said.

“Yeah,” Mike said. “He died … heatstroke, wasn’t it?”

“Yeah,” Manny echoed. “It was August and the heat index was something like a hundred and ten degrees. And the team was working out in full pads and everything.”

“What a memory!” Rose said.

“Football!” Alice’s lip curled.

“Okay,” Koesler said. “That’s the background all right. Now I’d like to read you excerpts from the column, which I’ll paraphrase, and comment on as we go along.

“Minnesota’s coach contended that Stringer’s death was ‘unexplainable’ and said that no one in the organization should feel guilt over it. But the cause of death was quite specific: heatstroke. If you accept the coach’s word ‘unexplainable’ you let the whole organization off the hook. ‘The inference is that because it was unexplainable, it was not preventable.’ But experts were unanimous that it was preventable. One expert called it ‘inexcusable.’ ‘No pro football player,’ he said, ‘should die of heatstroke … if the most basic attention is paid and precautions are taken.’

“‘Unexplainable. Inexcusable. Stand those two words side by side and you see why [the coach] clings so hard to his. If Stringer’s death was explainable, it was preventable. And if it was preventable it was inexcusable.’

“Then the writer asks what was so important about two-a-day practices in such crushing heat? Nothing, say physiologists everywhere.”

Koesler put aside the paper for a moment. “It just goes to enforce the image of the macho pro player,” he said. “Nothing stops the athlete. Not heat, not snow, not most injuries. ‘Suck it up,’ coaches say.

“There were lots of things the coaches could have done to avoid this useless and meaningless death. In weather too hot for football, they could have practiced without pads and merely walked through play patterns. They could have practiced early in the morning or late in the afternoon when the temperature was less hazardous and more conducive to survival. They could have seen to it that the players were taking enough liquids. And so on.

“The point this columnist makes is that Korey Stringer’s death was preventable, therefore inexcusable.

“Something like that could be said about Stan Benson. He could have confessed to his mother that he didn’t want to be a priest, that he wouldn’t be happy as a priest. His mother would have been hurt—maybe even devastated. But if she loved her son—and she did—she would have recovered.

“Father Simpson could have made the best of Guadalupe. Or he could have found a less hurtful way of trying to move up or be transferred … if that was, indeed, his motive—and that we’ll never really know; we can only guess.

“In any case, we ourselves could have been more sensitive in picking up signs. They were there—if more subtly.

“The solution to Stringer’s life-threatening episode is clearly more evident. But in either case, death was preventable.”

Koesler picked up the paper again. “Finally,” he said, “we turn to Rose’s question: ‘Who dun it?’

“There’s enough blame to go around in both examples of Stringer and Stan. But the point the columnist makes is worth thinking about. After puncturing the mystique of football and its insistence on the players pushing themselves beyond ordinary human endurance, the writer addresses the question:

“‘Stringer’s death was all too explainable: He was killed by an old idea. He was the victim of an archaic concept of toughness.’”

“And,” Koesler said, “I’d like to suggest that Stan Benson was killed by old law. Forget the coaches, the physical therapists, the heat, the pads, the dehydration, and all the rest. ‘Stringer was killed by an old idea. He was the victim of an archaic concept of toughness.’

“Forget us and Lily Benson and Father Simpson.

“In 1959, Pope John XXIII called for an Ecumenical Council and for the reform of Church law. He got his Council. But the Catholic world had to wait twenty-four years for the new code. The preceding code was promulgated in 1917. That was the code we studied in seminary. That was the one Pope John said needed revising. It was old law—but more than that, it was

deficient

law.

“Now, take deficient law and misinterpet or misapply it, and you come up with the cross Stanley Benson carried almost all his life. Hide behind deficient law to avoid recognition that it is unjust law, and you apply bad law to almost every problem.

“Illegitimacy

was

an impediment—though dispensable—to Orders. But to show how unimportant it proved to be, it’s not even mentioned in the new code.

“Stan was killed by old law. He was a victim of an archaic concept of law that was badly out of date.

“So this becomes not ‘who dun it?’ but ‘

what

done it?’

“Stan believed one thing and dispensed another. And he felt there was no escape in either case.”

Koesler knew that he was preaching to the converted. But from their facial expressions he perceived that he had given them a fresh concept to think on.

“When we began this evening, I mentioned that we might learn something from Stan’s life and his death. If we can help those who touch our lives—so that they never have to become victims of force or fear, so that they need never doubt God’s mercy and forgiveness, then I think we will have learned some valuable lessons from Stan Benson.”

Silence. Then Rose spoke. “Amen.”

The others nodded affirmation.

“How about we use this place for what it was intended,” Manny said, “and get something to eat and some coffee … and have some more talk.”

The group, now all smiles, stood and headed for the vending machines. Koesler held back. “Go ahead. I’ll be with you in a minute.”

He thought of all that had gone on over the years and—in an intensive way—the past few days.

He thought of a remark one of the gang had made tonight: “St. Stanley.”

Why not?

William X. Kienzle died in December 2001. He was a Detroit parish priest for twenty years before leaving the priesthood. He began writing his popular mystery series after serving as magazine editor and director of the Center for Contemplative Studies at the University of Dallas. He has been widely profiled in such places as

Writer’s Digest, the Chicago Tribune, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine.

He was among the distinguished contributors to the recent book

Why I Am Still a Catholic.