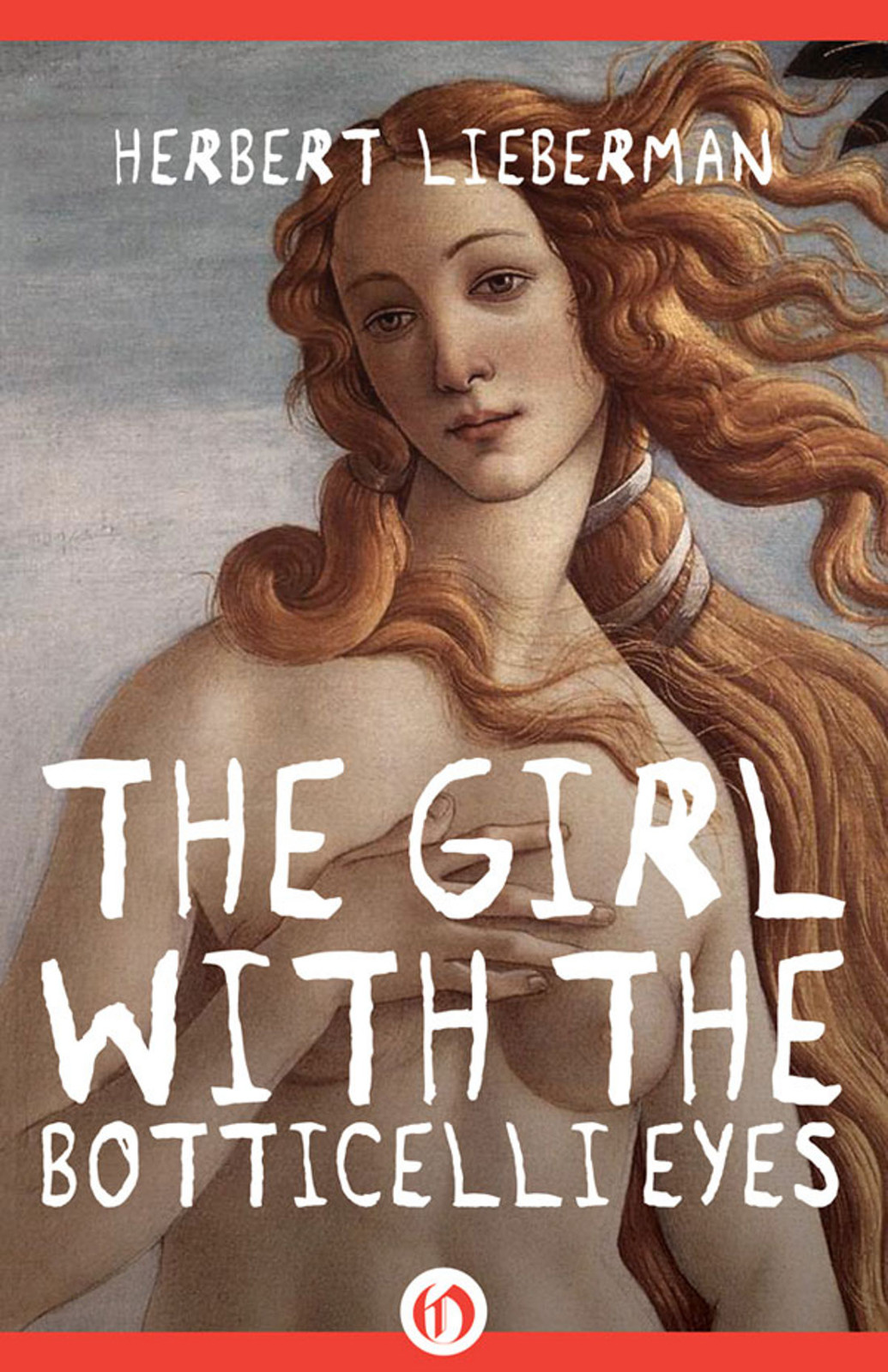

The Girl With the Botticelli Eyes

Herbert Lieberman

For Jean and Adrian Marcuse

I

T WAS HOT, SO

they left the doors open. If you stared at them for a while, you could see the waves of heat rising off the damp stone walk just across the threshold. Sunlight streaming through the branches of an olive tree outside washed the marble entryway in thick shadows of black and gray. And beyond the door, a jagged line of dome and corkscrew shapes stood silhouetted against a sky of dazzling blue.

It was nearly 5:30 P.M., and within the Church of St. Stephen, a tiny Christian church in Istanbul, it was a half hour to closing. St. Stephen’s is a little-known structure dating back to the time of Bajazet I. An extension of stone fortress built during the Crusades, it sits astride the western slopes of the Golden Horn. Never a major attraction to the general run of tourists, unlike Hagia Sophia, the Blue Mosque, the Dolmabahçe Palace, or the Topkapi, the church is known mostly to Turkish Christians and to art historians who come there from all parts of the world to view its chief attraction—the splendid Byzantine murals and mosaics over seven centuries old.

During this particular afternoon, the flow of tourists had been light but steady. Now, at this late hour, only a handful of people still lingered in the fast-fading light of the basilica.

St. Stephen’s sole security guard was an aged sexton. Imprisoned in a thick robe of gray twill, clearly hot and tired, the poor man did his best to fulfill a guard’s function. With the sun slanting westward and the great clock in the tower outside the church ticking off the few remaining minutes until closing, the sexton had grown noticeably restless. Shifting from one foot to the other, he watched the visitors circle the little area, view the various exhibits hanging there, light votive candles in the vestibule, then file out through the open door. On his face, he wore that expression of sullen resentment so characteristic of underpaid petty functionaries the world over.

One of the visitors lingered longer than the rest. A shapeless gray figure—ill-kempt but respectable—he wore a long, transparent raincoat of some synthetic substance—the sort that can be folded into a neat square and slipped into a jacket pocket. On the coat in question, the squares of the fold lines showed clearly in the straight gridlike ridges running both the length and width of the coat.

This person’s most prominent feature was a headful of bushy hair of nondescript color. A rather large pair of yellowish incisors protruded ever so slightly over his lower lip, forcing the mouth into an expression of fixed petulance.

In one of the tiny chapels off to the side, scarcely observed, the man stood riveted before a small painting. Executed in oil and tempera, in the thirty-two-by-forty-seven-centimeter category, it was attributed to Botticelli. The subject was a portrait of the good Centurion whose slave Christ heals, as told in the Gospels of both Matthew and Luke.

Here, the Centurion is seen in a simple three-quarter pose. Attired in a pale white belted tunic that barely hints at the muscularity of the figure below, his face is long and sharply lined, with high cheeks and eyes that convey a mixture of both power and gentleness. Upon the viewer, he turns the shrewd, vigilant gaze of a wise man, a knower of arcane things. It is a look of keen and disarming intelligence.

The man poised before this painting was now the last person in the church. Anyone near him would have been struck by his total absorption in the subject. A dreamy expression on his face, he muttered words half-aloud to himself, oblivious to his surroundings, or to the fact that the church was suddenly empty and that the sexton was now glancing with frank impatience in his direction.

In the next instant, the man’s arm rose. Something bright and metallic shot from the bottom of his sleeve. The sexton watched with fascination as the shiny object leaped upward to the top right-hand corner of the painting, then, with a single uninterrupted slash, plunged diagonally downward to the bottom left corner. A noise like ripping cloth followed.

The motion was repeated, this time starting at the upper left-hand corner, then once more descending with a fierce, rhythmic rage, over and over again.

Manship was in Munich, at the Alta Pinakothek, viewing paintings, when he was informed of it. Twenty-four hours later, he was back in Istanbul at the Church of St. Stephen, surveying the wreckage. The little chapel in which the painting had hung was cordoned off. A variety of forensic specialists and Turkish police padded noiselessly about, carrying out their duties. Though tourists were still permitted in to view other parts of the church, there was all about the place an air of hushed reverence, like a mortuary to which people have come to pay final respects to one recently deceased. As of yet, the police had picked up no suspects.

By means of an official pass authorized by the Turkish government, Manship was allowed into the chapel. He stood there now, silent and grim, gazing at the painting, the thing he’d viewed whole and gorgeous less than a fortnight ago. As a curator and the man charged with the responsibility of bringing the painting to the United States for a massive Botticelli retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum, he was beset by a horde of practical questions. First and foremost was to ascertain the degree of destruction sustained by the painting, then to determine whatever reasonable expectations he might have of repairing it in time for the exhibition’s opening in late September.

When Manship entered the church that morning, a blush of healthful pink had suffused his sharply angled features. Over the course of a few hours, his pallor had drained to something like that of old parchment. Less than two weeks ago, he’d left Istanbul ecstatic, having successfully negotiated terms for the painting’s temporary loan, the first time this startling Botticelli, virtually unknown in the West, would be exhibited. Now, in this ancient little church full of the dank musk of centuries, he was back again to see what might be salvaged from the pitiful ragged strips hanging on the wall there still in their frame.

Though the painting was unsigned, Manship had no doubt what it was. Layered with dust, encrusted with five centuries of grime, it hung in a dark niche at the rear of the tiny chapel, illuminated by no more than a few votive candles guttering in the damp, cryptlike air. But not even grime and dust and the absence of decent light could conceal the unmistakable brushwork, the streaks of dazzling color leaping like flames from out of the ruins of it.

It had taken his breath away, finding it there like that. Old Yampolski had talked about it on several occasions. But who listened to Yampolski these days? Manship had thought it was nothing more than an old man’s (albeit a brilliant old man’s) flight of fancy. A leading figure in the field of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century European painting, Yampolski was said to be failing rapidly, along with his memory and whatever meager worldly fortunes he’d managed to accumulate as an art critic and historian.

Manship had been so thrilled with the find that in a burst of gratitude he’d rewarded the old man with the job of writing the catalog for the show, his chief motive being to put some much-needed cash into his former teacher’s pocket.

The next morning, the

Centurion,

packed in crates specially designed to control temperature and humidity, then entrusted to the care of a team of trained couriers, lifted off the tarmac at Istanbul International Airport en route to Italy. Cabled ahead from Turkey, Signor Emilio Torelli cleared his work schedule and readied his staff and atelier to receive the badly mutilated canvas. Torelli was a genius. In the field of restoration he was looked upon as something of a miracle worker, his name uttered with a kind of hushed awe. He ran his shop on the outskirts of Florence in much the same manner as large urban hospitals run first-class emergency wards.

Torelli was Manship’s only hope. The

Centurion

had become the exhibit’s first casualty. Manship was determined there would be no others.

One

“T

WENTY-FIVE, TWENTY-FIVE

. Do I hear thirty? I hear thirty. Now I have thirty. Do I hear thirty-five? Gentleman over there in the corner with the handsome yellow necktie. Splendid. Thirty-five is my bid. Thirty-five. Come now, let’s not be shy. We can do better than thirty-five for this excellent museum-quality sketch. Forty is surely not too high. Lady Beresford. Splendid. We have forty. Forty thousand, then. We have forty thousand.”

The voice of the auctioneer droned on, piping numbers while the low murmur of some eighty or ninety people gathered in the small airless hall rose and fell upon his every intonation.

It was midsummer in London and the private Sotheby’s salon was packed with perhaps a dozen more bodies than it was ever intended to contain. Dusk coming on, an elderly white-haired attendant tottered around the room, lighting the small electric sconces that lined the walls at intervals.

“Sixty-five. Sixty-five.” The auctioneer’s voice prodded, taunted, and caressed.

Mark Manship sat there, knees crossed so lightly, they scarcely seemed to touch each other. His thatchy mane of salt-and-pepper hair had barely begun to recede at the forehead, and there was a certain elegant emaciation in the drawn, pallid lines of his face, like a Greco saint. Tall, gangly, boyish-looking, even in his late thirties, he seemed uneffaced by time.

Alert and upright in his chair, hands clasped in his lap, he gave an impression of innocence and inexperience that may have been just a bit disingenuous.

“Quatre-vingt.”

The words issued from a long, Gallic face belonging to a man known to Manship as the director of the Louvre. Manship’s eyes wandered upward to the ceiling above him. It was a Baroque ceiling, bronze and coffered into separate panels in which raised friezes depicted various mythological stories. Just above him, several plump cupids, their cheeks swollen, puffed into coach horns.

“Eighty. We have eighty,” cried the auctioneer at the block. “Who’ll give us eighty-five?”

The object of all this attention was a small Madonna drawn by Botticelli in the late fifteenth century. It was one of a series of thirteen small line sketches executed by the painter at the request of his powerful patron, Lorenzo de’ Medici.

“Note the curious mixture of vigor combined with delicate refinement,” said the auctioneer. His name was Philpot. “The verticality, the unbroken linear perfection, the absolute confidence of the stroke—” Philpot was much given to talk like that. It was his stock-in-trade. “Truly an excellent example, ladies and gentlemen. Mint condition. Eighty-five. Come now. Let’s hear you. Eighty-five. Very good. Right over there.”