The Glimmer Palace (22 page)

Read The Glimmer Palace Online

Authors: Beatrice Colin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #War & Military

A doctor came in and whispered that Lotte was needed in the operating room. She didn’t have much time.

“How’s Lilly?” the nurse asked. “I think about her a lot. And you.”

Hanne shrugged.

“We worked together in a bar. And then we got sacked.”

“And now?” the nurse asked. “Is she . . . ?”

“Here? No,” Hanne replied. “She’s still in Berlin as far as I know.”

The nurse placed a week’s supply of dehydration tablets in an envelope.

“Nurse von Kismet?” the doctor called.

“Two minutes,” she replied. “I’m sorry, Hanne, about what happened.”

“How could you have let them expel me?” Hanne said. “I lost my brothers. . . . They split them up and sent them away.”

Lotte held her head in her hands.What were the chances of meeting Hanne again? Not high. And yet, here she was. Maybe God was trying to tell her something. If only she could still hear him. She had nursed hundreds and hundreds of men, men with limbs missing, with metal in their heads, their hearts, their minds. And when the moment of death came, as it did more often than not, they all thought she was someone else, a mother, a wife, a sister. Yes, yes, I’m here, she would always say. And she would stroke and caress and, if no one else was around, she would kiss them. What did these little acts of intimacy mean? Nothing to anyone else. Everything to the men. But this morning, the man who lay on the trolley beside the latrine seemed to recognize her.What were the chances?

“Lotte,” he had whispered through cracked lips. “Is it you?”

She stared at him. At first he was just another shattered body that she couldn’t mend. And then his face seemed to come into focus.

“It is me,” she said. “I am Lotte.”

“I looked for you for weeks. I couldn’t stop thinking about you.”

She never cried. She never cried except this once. He died with his head in her arms and her mouth on his and this time she didn’t care who saw it. And even though his papers said he came from Hamburg, not Berlin, and even though the man in the park was tall and he seemed shorter, it was he, her lover.

When she had arrived at the front, all she desired was to leave no traces of herself; there would be no one to miss her, she had no shared histories or entwined narratives. But now she realized that this was impossible, that she couldn’t cut herself off completely and in fact she didn’t want to anymore. And she felt elated and yet devastated and then filled with regret.

“Maybe it was God’s will, Hanne,” she said.

“There is no God,” Hanne replied.

Nurse von Kismet smoothed down her face. There is no right and wrong anymore, she had decided, no good and evil. War, prostitution, love, sex, all the morality of the Church seemed meaningless, all the so-called values turned upside down.

“Come with me,” she instructed Hanne. “Quickly.”

They went to the hospital canteen and Lotte placed a bowl of thick meat soup in front of Hanne. A high-pitched screech followed by a loud boom came from a few miles away. It made the cutlery rattle and the china clink together. Hanne looked up at the former nun in alarm.

“The hostilities are coming closer,” Lotte said by way of explanation.

Everyone in the room, the cooks, the soldiers, the nurses, stood with heads cocked, waiting for the next sound. And then from nearer, much nearer, came the sound of gunfire. They all relaxed. Germany was still fighting back.

“Eat it all,” Lotte said. “And then go home.”

But Lotte knew the girl was unlikely to do either.

In Arcadia

F

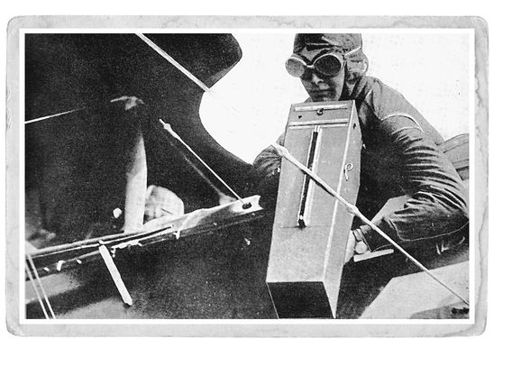

ebruary 1916. The night is overcast, no moon or stars; only the roar ofthe Fokker E-type’s engine as it flies toward France.Tonight there’s an extra passenger on the airplane to watch the bombardment: a

Film-Führer

, as he asks to be called, with his camera mounted so it points through the hatch and his pile of film, which he stores in a metal box. Below, when their eyes adjust, they can see the ammunition trains, the roads crawling with gray, the soldiers in formation moving toward the front, even the new artillery, the Minnenwerfers, which can, they say, toss a bomb as big as an oil drum.

“Look!” the

Film-Führer

shouts. “Below!”

Like huge silent fish without eyes are the zeppelins. Heading toward Lorraine, toward Revigny, toward Verdun, they cross into enemy territory to chart British positions, their guns, their camps, their trenches. But then a shell, a shot, a shooting star of light, is fired up into the night. Two searchlights point their fingers into the mist, back and forth and back and forth again.The

Film-Führer

begins to pray.

The enemy catch a zeppelin in their prongs and start to fire. They hit. The airship tips, turns pink, and bursts into flame. Up in the Fokker they watch it fall through the sky below, a blaze of white, an arc of skeletal metal, a crumpled heap in a muddy field.The sky is lightening in the east.The other

zeppelins begin to drop their bombs; the German guns begin to fire.The battle for Verdun has started.

The cart horse swayed and then sank forward to its knees. The boy with the reins in his hands and the sob in his voice started to shout, “Come on! . . . Gee up! . . . Move! Why have you stopped? Move! Please move?” He hit the horse’s ridged brown back with his whip, once, twice, three times. The horse flinched, showed the whites of its eyes, and then with a small moan, a letting out of breath, of steam, of life, it slumped and collapsed into a heap of angular bone and sagging skin.

Lilly wasn’t the only one standing on Mariannenplatz who was watching. No sooner had the horse’s head hit the cobbles than a dozen women appeared from doorways and alleyways armed with knives and bowls and cups.They ignored the boy’s cries, his tears, his laments, and began to butcher the carcass, sawing through bone and slicing through veins to let the spurt of warm blood flow into their bowls. One woman, her face splattered with red, tried to hack off a ragged haunch with a penknife; another pulled out the tongue. In minutes, what was left of the horse would vanish completely. Lilly pushed to the front. All she had eaten for months was turnip—raw turnip, since there was rarely any coal to be had. She looked down at the skin and bone that remained and tried to convert it in her mind into something edible. She forced herself to think of stew, of soup, of meat. It was so long since she had eaten any, she had almost forgotten the taste. And yet she tried to make the connection. Horse . . . food; food . . . horse.The thought filled her mouth with bile and she had to resist the urge to gag. There was someone pulling at her skirt. It was the boy.Tears were streaming down his face.

“My mother,” he sobbed. “What will my mother say?”

Lilly crouched down next to the bloody remains of the horse. An old woman was pulling out the horse’s innards. She had the liver in her hands.

“Give it to the boy,” Lilly said.

The old woman, whose apron was already full, hesitated. Her eyes swiveled round to look at Lilly, to see if it was just a ruse. The sound of the boy’s sobs was almost unbearable. Lilly held the old woman’s gaze. And so, with much shaking of her head and cursing of the government, she pulled a piece of newspaper from her bag, wrapped up the horse’s liver, and handed it over.

If anyone ever asked the silent film star Lidi—or Lilly, as she was known then—about the hardships in wartime Berlin, her eyes would glaze over and she would suggest that she had suffered, but not as much as most people. She would be vague with dates and places and specifics, so vague that it did indeed seem as if, like an accident victim, her subconscious had wiped her memory almost clean.

In fact, on that day in April 1916, she had been living in a hostel for unmarried Catholic women for a year. With only her orphan’s allowance to live on, Lilly had been allowed to make up the rent in cleaning duties. Every morning she would sluice out the latrines with scalding hot water and scrub the floor with carbolic soap. And every night she would do it all over again. And no matter how well she had done it the previous time, how scalded her hands had become and how many new blisters she had acquired, the floor was always filthy when she went down on her knees with her scrubbing brush in hand and the latrines were always caked with excrement and plugged with soiled newsprint.

Her bed, one bunk in a room of four, was damp and full of fleas. Since many of the other women didn’t believe in bathing during winter, the smell in the room at night was suffocating.There was a single stove for the whole floor, and when there was enough fuel, each woman was allocated fifteen minutes. But it was loosely policed, and as all cooking was prohibited after nine, Lilly often waited all evening for nothing. Nobody spoke to her and she spoke to no one. She developed a hacking cough and at night the other women begged the Virgin Mary to either let her die or get better but make it quick.

She was more likely to die in there, she assessed quite unemotionally, than recover. The price of food kept rising and the queues for food kept growing longer. Living on stale bread and raw vegetables, she had barely enough energy to do much more than simply get through the day. It was as if a large part of her had shut down and the only visible remaining part of her was the part that ached, that was always hungry, that would do almost anything to survive.

Lilly turned back to the horse. She pulled out her water pail and quickly began to pick up what she could find: a bone, a rib, a stringy piece of flank. And then she was aware that someone was watching her. She looked up. A woman was staring at her over the remains of the dead horse, a woman wearing clean white gloves and holding a camera. Without warning, she raised the camera to her eye and took a photograph.

“Don’t,” Lilly said, shielding her face with her hand. But it was too late.The picture was already taken.

“Still reading poetry?” the woman asked as she wound the film. The remark was so incongruous that Lilly barely took it in.

“You’re the Luisenstadt girl?”

The woman seemed oblivious to the pandemonium around her. An old man squeezed in front of Lilly and started to spoon up the horse’s spilled innards from the filthy cobbles with a battered ladle, splashing her dress with blood. Wash day wasn’t until the weekend. Her eyes swam. She tried so hard to keep clean, to look respectable. What was the point?

“You don’t remember me?” the woman continued.

The woman did look vaguely familiar. But most people had become ghostly facsimiles of who they had been two years earlier, and unless you were sure of someone’s identity, it was better to glance away than to be mistaken.Without answering, she turned and began to make her way back through the crowd.

It was late afternoon and the rush hour had started. A tram was at a standstill behind the horseless cart and was blaring its horn. As a traffic jam began to grow in both directions and a group of women squabbled over what was left of the carcass, as the boy sat on the curb with a lump of bloody newspaper in his hands and watched as someone made off with the horse’s head on his shoulder, the woman with the camera appeared at Lilly’s side.

“My brother and I ran you over on the road to Potsdam,” she said. “Don’t you remember? It does seem such a long time ago.”

Lilly stopped and stared at the woman’s face, at the flint-colored eyes and the wide cheekbones. Now she remembered her.

“I gave you some boots, which I see you’re not wearing. Not that I blame you: they were an unfortunate shade.”

The woman smiled at her expectantly. As she stood there with her filthy dress and her pail full of warm horsemeat, Lilly was ashamed: ashamed of how she looked, ashamed of what she had done, ashamed of who she was.

“Can I take your portrait?” the woman asked suddenly. “We could do it at the apartment. I’m putting together a series.”

For an instant Lilly thought she was making fun of her.

“I don’t think so,” Lilly replied.

“I’d pay you,” the woman quickly countered. “I haven’t got that much, but if you name a figure, I’m sure we could come to some arrangement.”

Lilly felt her cheeks begin to color. She had heard those words many times before, always from men. A figure, she could name a figure: ten marks, twenty. She could do it, she would tell herself, what did it matter? Hanne could. Thousands of other women could, so why not her? Think of the money. Just think of the money. And yet, as soon as the decision was made, she would remember the clatter of metal instrument on metal bowl, the suffocation of a hand across her mouth, the memory of her body starting to split and bleed, and she could not.

“No, thank you,” she said, and started on her way again.

“I’ll make you dinner, then.”

Dinner

: the word was as foreign as “picnic” or “luncheon.” Large white plates and linen napkins; plates of peaches and purple figs; legs of lamb and roast potatoes. She was dreaming; she often drifted away like this, her mind filled with images and tastes that she hadn’t even experienced firsthand, generic memories she didn’t even own. The woman’s small blue eyes had widened and she had reached out, almost touching her on the arm, making her stop.