The Gods of Atlantis (63 page)

Read The Gods of Atlantis Online

Authors: David Gibbons

Of great significance for this novel, the Zoo tower also provided safe storage for art and antiquities from numerous Berlin museums, held in special air-conditioned rooms on the third floor – among them the Egyptian bust of Nefertiti, the carved frieze from Pergamon in Turkey, Kaiser Wilhelm II’s collection of coins and, most famously, the ‘Treasure of Priam’, excavated by Heinrich Schliemann at Troy in

1873, donated by him to the German people before his death in 1890, and held until the the beginning of the Second World War in the Museum for Pre- and Early History in Berlin.

In March 1945, under orders from Hitler and overseen by Reichsleiter Martin Bormann, many of the treasures in the Zoo tower were removed to a salt mine at Merkers in Austria, where they were discovered soon after by soldiers of General Patton’s US Third Army. Three crates were left behind; those containing the treasure of Priam. We know this because the Treasure disappeared after the war and for many years was thought lost. The true course of events has only recently been reconstructed, and much remains uncertain. The director of the Museum for Pre- and Early History, Dr Wilhelm Unverzagt, an ardent Nazi, is thought to have insisted that the crates remain in Berlin when the other treasures were removed in March 1945, though whether or not there was a higher authority behind that decision – Himmler would be a likely candidate, with his interest in prehistory – remains unknown. Unverzagt is thought to have stayed in the Zoo tower with the crates after the 2 May surrender to ensure that they were not looted by Russian soldiers but instead remained intact for transport to Moscow, where they remained hidden in the storerooms of the Pushkin Museum until they were rediscovered in 1987.

In the novel, I imagine the ‘Schliemann Gallery’ in the Museum for Early and Pre-History being presided over by a statue bust of Otto von Bismarck, the ‘Iron Chancellor’, who had been a friend of Schliemann’s; my image of the broken statue in the Zoo tower is based on a real-life shattered statue of Bismarck photographed in 1945 in the town square of Rigorplatz, outside Berlin, and the fictional statue in turn inspires the fictional Hoffman to think of Ozymandias, the toppled statue of the king in Shelley’s poem who seems to stand for all the crumbled dreams of power that Hoffman would have seen around him in those dark days of April 1945.

The Zoo tower provided a headquarters for Josef Goebbels in his final guise as Reich Commissioner for the Defence of Berlin, though he himself did not leave the Führerbunker in the days leading up to the

murder of his children and his own suicide. The words and actions of Heinrich Himmler portrayed in this novel are fictional, including his appearance at the Zoo tower on the morning after Hitler’s suicide on 30 April 1945. Nevertheless, Himmler’s movements over the final days before the German surrender were secretive and shrouded in mystery, and allow the possibility of a clandestine visit to Berlin as suggested here. On 28 April 1945, the BBC had reported Himmler’s attempt to negotiate with the Western Allies, and the following day Hitler declared him a traitor and ordered his arrest. Late on 1 May, Himmler attempted to negotiate with Grand Admiral Dönitz, Hitler’s appointed successor, for a place in the new government, and over the next days he followed Dönitz and his puppet government from Plön to Flensburg on the Baltic. Despite being dismissed by Dönitz on 6 May, Himmler continued to retain the trappings of power, driving round with an SS escort and maintaining an aircraft. He was finally arrested in disguise – wearing an eye patch, with his moustache shaved off – by the British, and committed suicide in custody using a cyanide capsule on 23 May.

Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant-Colonel) Ernst Hoffman is fictional. In my story, Himmler promotes him two ranks higher to the SS equivalent of brigadier, SS-Brigadeführer. A real-life Stuka ace was closely associated with the Zoo tower: Oberst (Colonel) Hans-Ulrich Rudel, one of the most highly decorated German servicemen of the war, with over 2,500 combat missions to his credit. Rudel was a committed Nazi and much feted by the Nazi inner circle. On 8 February 1945, he was shot down and sent to the hospital in the Zoo tower to recover, spending over a month there and being visited by Goebbels and Göring. In a rare eyewitness account from inside the tower, Harry Schweitzer, a Hitler Youth flak auxiliary, described how Rudel was allowed on to the roof to see the 37mm guns in action, a matter of some interest to him as his Stuka mounted a version of the same weapon. Schweitzer was one of many Hitler Youth and Luftwaffe boy auxiliaries who manned the flak guns in Berlin, and he gives a vivid account of the final days in the Zoo tower: the terrible overcrowding, the asphyxiating conditions, attacks by dive-bombers, and the pulverizing effect of the

128mm guns when they were fired at low elevation into the city, causing shock waves so severe that they damaged the parapet of the tower. Colonel Hans-Oscar Wohlermann, a Panzer Corps artillery officer, described the horrific view from the gun platform: ‘One had a panoramic view of the burning, smouldering and smoking great city, a scene which again and again shook one to the core.’

Harry Schweitzer also described the announcement that came through internal tannoys for a breakout from the Zoo tower at about 2300 hours on 1 May. The tower was surrendered to the Soviets about an hour and a half later. A Luftwaffe doctor present, Dr Walter Hagedorn, estimated the numbers inside at more than 30,000 – mostly civilians – including 1,500 wounded and 500 dead. Miraculously, most of the survivors were able to leave unharmed. The circumstances of the final day in the tower are hazy, but provide a basis for the fictional scenario in this novel. On the evening of 30 April, the Russians sent German prisoners to the tower to try to persuade the garrison to surrender, assuring them that there would be no executions. The following morning, the Russians received a reply, signed by Colonel Haller, garrison commander, saying that the surrender would take place at midnight. But Haller had not been the official garrison commander, suggesting that there had been a coup; the reason for the delay was apparently to allow time for a breakout, on the assumption that the Russian assurances were worthless. In the event the breakout never occurred and the Russians reached the tower and took the surrender from Haller, who apparently told a Russian officer that two high-ranking generals were hiding inside. The Russian writer Konstantin Simonov was led to a concrete room, where he found one of the generals lying dead, eyes wide open and clutching a pistol, a dead woman by his side, and between the general’s legs ‘a bottle of champagne, one third full’.

The idea that Hoffman could have flown out of Berlin in a Fieseler Storch is based on a true-life episode from those final days of Nazi power, when the celebrated Nazi aviator Hanna Reitsch (herself also treated in the Zoo tower hospital, in 1943) flew the wounded Luftwaffe

general Ritter von Greim into Berlin and then out again after he had visited the Hitler bunker. They survived Russian anti-aircraft fire and landed on a Berlin street in a badly damaged Storch on 27 April, leaving two days later in an Arado Ar 96, hours before Hitler’s suicide. Both aircraft types were lightweight, but the Storch in particular excelled at short take-off and landing.

After the surrender, the Zoo tower was used as a hospital and a shelter for the homeless, but in 1947 it was demolished by the British Royal Engineers, a huge job requiring a staggering thirty-five tons of dynamite. The resulting mountain of rubble – 412,000 cubic metres of it – was ground up and used for road construction during the 1950s, and in 1969 the foundations of the tower were removed. Today the site is occupied by the hippopotamus enclosure of the Berlin Zoo. To get a sense of its appearance, you can visit the remains of another of the three huge towers, the Humboldthain flak tower, which still survives on one side to its original height and has been converted into a memorial and viewing tower. Since 2004, the Berliner Underwelten Association has offered tours inside the ruins, and their efforts have revealed much that was previously buried. Whether or not more remains to be discovered at the site of the Zoo tower is unknown, but the enormous effort that went into its construction in the heart of Berlin suggests that more secrets of the Nazi period and those apocalyptic final days may yet be revealed beneath the modern city.

B-24 Liberator FK-856 is fictional, but is based on RAF Liberators that flew out of Nassau in the Bahamas as part of 111 Operational Training Unit until July 1945. The fictional pilot’s experiences with Bomber Command are inspired by the wartime career of my great-uncle, Flight Lieutenant William Norman Cook, DFC and Bar, RAF, a Lancaster pathfinder pilot who flew 59 operations over Nazi Europe. 111 OTU also carried out anti-submarine patrols, and their losses over the ‘Bermuda Triangle’ – no greater than the losses in any other training unit anywhere – included one Liberator that disappeared without trace on a training mission in 1945. Whether U-boats entered the Caribbean

after the German surrender in May 1945 may never be known; the possibility is suggested by the extraordinary voyages of U-977 and U-530, whose captains refused to surrender and did not finally give up until 10 July and 17 August respectively, at Mar del Plata in Argentina.

The Prologue invokes imagery from

The Epic of Gilgamesh

, the ancient Near Eastern poem also known in its Akkadian version by its first line,

Shanaqbai-muru

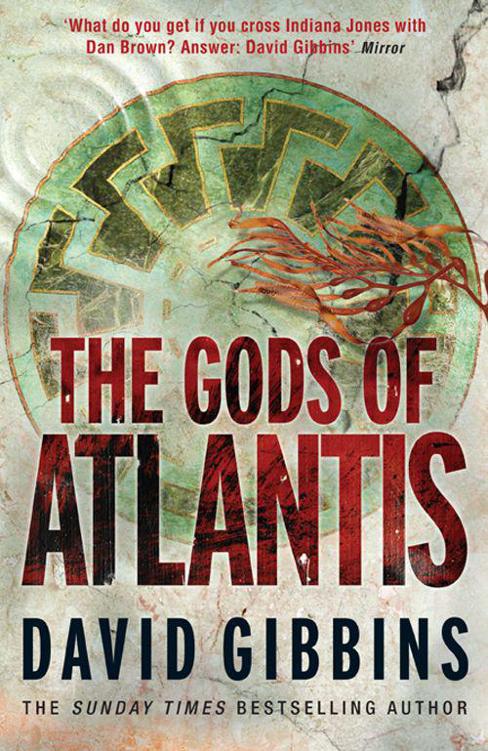

, ‘He who saw the deep’ (in the Prologue I have imagined a similar meaning for the name Uta-napishtim, in a lost language). The passage quoted at the beginning of the book is my own rendering, though the translation of words and phrases owes much to previous scholarly versions including those of Reginald Campbell Thompson (1928), N. K. Sandars (1960 Penguin edition) and Andrew George (1999 Penguin edition). The modern poems referred to in this novel are Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘Kubla Khan’ (Chapter 7), Wilfred Owen’s ‘Strange Meeting’ (Chapter 16) and Walter de la Mare’s ‘The Listeners’ (Epilogue). The cover image is based on the Nazi

Sonnerod

symbol in the floor of the SS Generals’ Hall at Wewelsburg Castle in Germany. Other images of sites and artefacts in this book are on my website www.davidgibbins.com