Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

The Good and Evil Serpent (90 page)

The compiler of this appendix to Mark was influenced by Greek mythology. Dionysus, who appears as a serpent, gave his devotees the power to handle serpents. Thus, like Athena, they, the Bacchantes, were possessed and could hold deadly snakes. Most likely in Mark 16:18 the serpent primarily symbolizes the Death-Giver (Neg. 1).

JOHN 3:14

Initial Observations

The Gospel of John was composed and edited over three or four decades, reaching its present form, without the story of the adulterous woman (7:53–8:11), which was inserted later, about 95

CE

.

22

The work may have been first composed in Jerusalem in the mid-sixties and later edited and expanded elsewhere, perhaps in Antioch or Ephesus.

23

For almost two thousand years, Christians have assumed that the Fourth Evangelist, of all the Evangelists, was the one most influenced by Greek thought and was dependent on the Synoptics (Mt, Mk, Lk), and that the Beloved Disciple who appears only in the Fourth Gospel as the disciple “whom Jesus loved” (Jn 13:23) is to be identified with the Fourth Evangelist. Since the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, it has become obvious to many Johannine experts that the Fourth Gospel is the most Jewish of the Gospels.

24

Recently, P. Borgen, D. M. Smith, and other Johannine experts have rightly pointed out that the Fourth Evangelist may have known one or more of the Synoptics, but wrote “independently” of them.

25

In the past fifty years, Johannine experts have demonstrated why the Fourth Gospel is probably not apostolic or connected with the Apostle John but took its final form, perhaps, in Ephesus. Among the most important insights is the perception that this John and his brother—the sons of Zebedee—never appear in the Fourth Gospel, and it would be inexplicable why the Transfiguration, which was witnessed by John and would be so appropriate for the Fourth Evangelist’s cosmic theology, would be omitted.

26

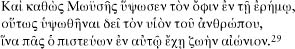

Figure 81

. Bronze Symbol of Diana (Artemis). Deer with serpent around neck. From Ephesus [?]. Early Roman Period. JHC Collection

M. L. Robert draws attention to an approximately 7-meter-long headless bronze serpent, rising up, with markings for scales and seven curves. Found with a bust of Tiberius and Livy in a Roman ruin at Ephesus, it is highly symbolical, representing a domestic cult. Most likely it symbolized protection (Pos. 6) and prosperity (Pos. 2).

27

Such images helped to clarify that only Rome was powerful and that the emperor was like a god, since the images of human heroes must be life-size but emperors and gods could be over 7 meters high.

28

Text and Translation

There can be little doubt that the passage on which we are focusing was carefully composed by the Fourth Evangelist and reflects the culture of the first century. Here is the text and translation, with key symbolical words italicized in the translation:

And as

Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness

,

So

it is necessary

for

the Son of Man to be lifted up

In order that

all who are believing

in him may have

eternal life

.

[Jn 3:14–15]

30

Arriving at this point in the study of ancient serpent symbolism, many readers might assume that the author of John 3:14 makes some connection between Jesus and the serpent. That is the understanding that slowly impressed me.

The possibility that the Fourth Evangelist is drawing some analogy between the serpent and Jesus is unthinkable if the serpent symbolizes evil.

31

However, the reader now knows that serpent symbolism was multivalent especially when the Gospel of John was being written and shaped.

32

Most readers will now comprehend why the Apocalypse of John and its portrayal of the serpent as Satan is not the proper perspective from which to understand chapter three of the Gospel of John.

Questions

As with Genesis 3 and Numbers 21 some questions arise, although they are not so numerous. Why does the Fourth Evangelist turn to an exegesis of Numbers 21 to make a point? Why does he attribute the teaching to Jesus? Was he imagining Moses’ serpent as a “pre-Christian” symbol of Jesus? Was he imagining Moses’ serpent as a type of Jesus? If so, what meaning was the author attempting to communicate and why?

Does the Fourth Evangelist in John 3:14–15 only make a comparison between the serpent and Jesus in terms of the verb “to lift up”? That is the usual advice of commentators,

33

but is it accurate, partially correct, or misleading? Does “to lift up” refer to the lifting up on a cross and, if so, why does the Greek verb never have that meaning? Does the verb denote Jesus’ being lifted up into heaven and returning to the Father? What is the meaning of the “as” and “so” that begin the first and second stichoi? What is the precise meaning of the passive verb “be lifted up”? Who is the Son of Man? What is meant by “believing in him”? Is there any connection between “the serpent” and “eternal life”?

The well-known zodiac circle and its animal signs were employed symbolically by many Christians; they appear, for example, in Revelation. The palm and the crown were accorded Christian meaning. The vine and the tree of life from the Genesis story were used symbolically.

34

The ship was used to signify the early church buffeted by the seas of time. The plow and the axe symbolized the Christian interpretation of Isaiah 2:3–4 and the dream when people “will beat their swords into plowshares.” Especially the fish, which is

ichthus

in Greek (an acronym:

ich

denotes Jesus Christ,

th

is Theou [= of God],

u

is

huios

[= Greek for “ the Son,” and

s

[= Savior]), and “living water” were employed to represent the Christian confession.

35

These symbols, some of which clearly originated in “pagan” cultures, were incorporated and redefined by Christians. Why was the serpent not a symbol widely used in Early Christianity as it was in the Asclepian cult—and was serpent symbolism employed in some communities? Why has virtually no Johannine scholar seen that Hellenistic and early Jewish serpent symbology may also clarify and enrich our understanding of the serpent in John 3:14–15?

One explanation is that the serpent is often always misperceived as a symbol of evil. Jews, Christians, and Muslims tell me repeatedly, before we discuss the traditions, that the serpent symbolizes Satan or the Devil. Another reason for the failure to perceive the richness of serpent symbol-ogy in antiquity is that the animal, concept, and symbolism are surprisingly absent in many reference works. For example, there is no entry for “serpent” or “snake” in G. Cornfeld et al., eds., the

Pictorial Biblical Encyclopedia

(1964).

Scholars’ Reflections

Do Johannine experts not clearly see a connection between Jesus and the serpent in John 3? Fortunately, the specialists on the Fourth Gospel avoid the temptation to see Jesus as an evil or poisonous snake. The closest to this absurdity would be the suggestion that the Son of Man represented poison. In fact, J. G. Williams argued the “Son of Man who is lifted up was accused of being ‘poison.’ “ He continued: “Unlike the serpent Moses held up, he [Jesus] is not poison.”

36

Nowhere in early Jewish thought or in traditions that have shaped or appear in the New Testament can I find textual support for such a supposition. Fortunately, Johannine scholars are more informed and perceptive.

The German M. Claudius, by his own admission, loved to study the Bible, especially (“am liebsten”) the Gospel of John. Using the exegetical method that was acceptable in his time, but is today recognized as conflationism (e.g., the mixing of Moses’ ideas with those of the Fourth Evangelist), Claudius argued that Moses, in the upraised serpent of the wilderness period, perceived what would transpire centuries later and in Jerusalem: the crucifixion of the Son of Man.

37

Johannine scholars are more diachronically sophisticated than Claudius; they do not make the mistake of assuming Moses had foreknowledge of Jesus.

Yet we must ask again: Do they see a connection between the serpent and Jesus? The answer is clearly “no;” they either miss the poetry that makes “the serpent” parallel to “the Son of Man” (see the following discussion) or they assume no comparison was intended by the Fourth Evangelist. This should not be revolutionary news, since we drew attention to commentators’ failure to include ophidian symbology in an exegesis of John 3:13–16 in the opening pages of this book.

The commentators have unanimously opted for another comparison, observing that the grammar demands a comparison (note “as” followed by “so;” see the following discussion). Johannine experts conclude that the comparison in John 3:14–15 applies only to the verb “to lift up.” Note again some pertinent comments:

The phrase “to be lifted up” refers to Jesus’ death on the cross. This is clear not only from the comparison with the serpent on the pole in vs. 14, but also from the explanation in xii 33. [Brown, 1966]

38

…. the deepest point of connection between the bronze snake and Jesus was in the act of being “lifted up.” [Carson, 1991]

39

And, just as that snake was “lifted up” in the wilderness, so, Jesus says, “the Son of Man must be lifted up.” This must refer to his being “lifted up” on the cross. [Morris, 1995]

40

Und wie Gott in der Wüste seinen Zorn gegen das rebellische Volk durch die Rettungsgabe der erhöhten Schlange überwunden hat, so hat er Jesus … durch seine Hingabe und Erhöhung an das Kreuz—zu retten. [Wilckens, 2000]

41

In dem Johannes den “erhöhten” Menschensohn … gibt er den gekreuzigten Jesus als Zeichen zu verstehen, das auf Gott weist. [Wengst, 2000]

42

In an erudite and insightful study on John 3:14–15, R. R. Marrs shows no interest in serpent iconography or symbology and misses the comparison between Jesus and the serpent.

43

For him, “the point of comparison” is clearly “not between Moses and Jesus, since Moses is the lifter of the serpent, while Jesus is the one lifted. The immediate point of comparison seems simply the lifting up that occurs in both scenes” (p. 146).

One of the most distinguished and gifted Johannine experts, and one who is probably the most informed specialist on what is a consensus in the study of John has served us well. In a book that appeared when the present work was nearing its completion, D. M. Smith summarizes the consensus on the meaning of John 3:14. Note his words:

The biblical scene in view here is Num 21:8–9, where the Lord instructs Moses to make an image of a serpent and elevate it on a pole, so that the rebellious Israelites, against whom the Lord had actually sent serpents in the first place, might, if snake bitten, look on it and live. The analogy with the work of the crucified Jesus, the Son of Man who is lifted up, is very striking indeed. It is a classic typology. The element that is new in John, and characteristically Christian, is the emphasis on belief, which is absent from the story in Numbers. (Of course, comparisons of Jesus with the serpent are misplaced; the analogy applies only to being lifted up.)

44