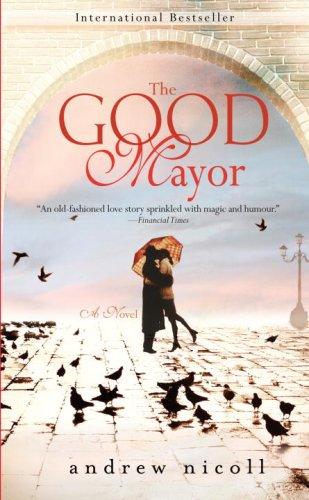

The Good Mayor

Authors: Andrew Nicoll

Tags: #Married women, #Baltic states, #Legal, #General, #Romance, #Fiction, #Mayors, #Love Stories

PRAISE FOR

The Good Mayor

WINNER OF SCOTLAND’S

SALTIRE SOCIETY FIRST BOOK AWARD

“An exuberant, whirlwind read.”

—

The Guardian

(London)

The Guardian

(London)

“Every now and then, a first novel reads like the culmination of a lengthy literary career…

The Good Mayor

is a case in point.”

The Good Mayor

is a case in point.”

—

Financial Times

Financial Times

“A smoldering siren and likeable hero delight in a romance with charm… Nicoll convincingly builds and maintains the sexual tension between his leads in a way that will keep readers hooked.”

—

The Sydney Morning Herald

The Sydney Morning Herald

“A literary novel and gorgeously written, old-fashioned romance.”

—

The Australian Women’s Weekly

The Australian Women’s Weekly

“Audacious in conception, inspired in execution, this fable-like novel of love, loss and friendship set literary tongues wagging… A dexterity and lightness of tone that plies its way between tongue-in-cheek whimsy and world-weary omniscience.”

—

The Canberra Times

(Australia)

The Canberra Times

(Australia)

“A wonderfully warm and comforting experience …

The Good Mayor

is a marvellously satisfying tale, evocative, moving and gently funny in a manner that recalls Jane Austen.”

The Good Mayor

is a marvellously satisfying tale, evocative, moving and gently funny in a manner that recalls Jane Austen.”

—

Herald Sun

(Australia)

Herald Sun

(Australia)

“A story of love, dreaming and loss, magical realism … You will not be disappointed.”

—

The Observer

(London)

The Observer

(London)

AN

L

AW

N THE YEAR BLANK, WHEN A-K WAS GOVERNOR

N THE YEAR BLANK, WHEN A-K WAS GOVERNORof the province of R, Good Tibo Krovic had been mayor of the town of Dot for almost twenty years. These days, not many people visit Dot. Not many people have a reason to sail so far north into the Baltic, particularly not into the shallow seas at the mouth of the River Ampersand. There are so many little islands offshore, some of them appearing only at low tide, some of them, from time to time, coalescing with their neighbours with the capriciousness of an Italian government, that the cartographers of four nations long ago abandoned any attempt to map the place. Catherine the Great sent a team of surveyors who commandeered the house of the harbour master of Dot and lived there seven years, mapping and remapping and mapping again before they finally left in disgust.

“C’est n’est pas une mer, c’est un potage,” the Chief Surveyor memorably remarked, although nobody in Dot understood him. Unlike the Russian nobility, the people of Dot did not express themselves in French. Neither did they speak Russian. For, despite the claims of the Empress Catherine, the people of Dot did not count themselves as Russian. Not at that time. At that time, the men of Dot—if anyone had cared to ask them—might have spoken of themselves as Finns or Swedes. Perhaps, at some other time, they might have nodded to far-off Denmark or even Prussia. Some few might have called themselves Poles or Letts but, for the most part, they would have stood proudly as men of Dot.

Count Gromyko shook the mud of the place from his feet and

sailed home for St. Petersburg, where he confidently expected a new position as Her Imperial Majesty’s chief horse wincher. But, that very night, his ship struck an uncharted island which had impolitely emerged from the seas around Dot and he sank like a stone, taking with him seven years’ worth of maps.

sailed home for St. Petersburg, where he confidently expected a new position as Her Imperial Majesty’s chief horse wincher. But, that very night, his ship struck an uncharted island which had impolitely emerged from the seas around Dot and he sank like a stone, taking with him seven years’ worth of maps.

The admirals of the Empress Catherine were left with a blank space on their charts which they were far too civilised to mark “Here be Dragyns” so, instead, they wrote, “Shallow waters and foul grounds, dangerous to navigation” and left it at that. And, in later years, as the borders of many different countries shifted around Dot, like the unreliable banks of the River Ampersand, it suited their governments to say no more about it.

But the men of Dot needed no maps to navigate the islands which protect their little harbour. They found their way through the archipelago by smell. They guided themselves by the colour of the sea or the patterns of the waves or the rhythm of the current or the position of this eddy or that piece of slack water or the shape of the breakers where two tides crossed. The men of Dot sailed confidently out of their harbour seven centuries ago, taking skins and dried fish to the ports of the Hanseatic League, and they sailed home yesterday with cigarettes and vodka that nobody else need know anything about.

And, like them, when Good Tibo Krovic went to work in the mayor’s office each morning, he navigated confidently. He picked up his paper from the front door, walked down the blue-tiled path, through his neat little garden to the collapsing ghost of a gate where a brass bell hung from the branches of a birch tree with a chain ending in a broken wooden handle, green with algae.

On the street, Tibo turned left. He bought a bag of mints from the kiosk on the corner, crossed the road and waited by the tram stop. On sunny days, Mayor Krovic read the paper while he waited for the tram. On rainy days, he stood under his umbrella and sheltered his paper inside his coat. On rainy days, he never got to read his paper and, even on sunny days, likely as not, somebody would come up to him at the tram stop and say, “Ah, Mayor Krovic, I was

wondering if I could ask you about …” and Good Tibo Krovic would fold his paper and listen and advise. Good Mayor Krovic.

wondering if I could ask you about …” and Good Tibo Krovic would fold his paper and listen and advise. Good Mayor Krovic.

City Square is exactly nine stops from Mayor Krovic’s house. He would get off after seven and walk the rest of the way. Halfway there, he would stop at The Golden Angel and order a strong Viennese coffee with plenty of figs, drink it, suck one mint and leave the rest of the bag on the table. Then there was only a short walk down Castle Street, across White Bridge, through the square and into the Town Hall.

Tibo Krovic enjoyed being mayor. He liked it when the young people came to him to be married. He liked visiting the schools of Dot and asking the children to help design the civic Christmas cards. He liked the people. He liked to sort out their little problems and their silly disputes. He enjoyed greeting distinguished visitors to the town.

He enjoyed walking into the council chamber behind the major-domo carrying the great silver mace with its image of St. Walpurnia—St. Walpurnia, the bearded virgin martyr, whose heart-wrung pleas to Heaven for the gift of ugliness as a bolster to her chastity were answered with a miraculous generosity. St. Walpurnia who was twice blessed by God—first with a beard of monstrous luxuriance and then with a cataclysm of warts which covered her whole body and which she exposed to the men of Dot almost daily in a tireless effort to turn them away from sin. St. Walpurnia who, when the rampaging Huns threatened Dot, offered herself to them on condition they spared the womenfolk of the city. St. Walpurnia who, as the monks recorded, ran towards the Hun camp, calling out to them, “Take me! Take me!” and those beastly Huns, who thought nothing of slaking themselves in the hairy flesh of their camp animals, treated poor, saintly Walpurnia as a mere plaything. When she died, hours later, crying out, “Oh God, oh God, oh Jesus!,” the legend said there wasn’t a mark on her entire warty body. God granted her a heart attack as another mark of his extreme favour and, when her corpse was recovered, a smile of bliss shone out from beneath her velvety moustache as a

sign that she had already entered into the delights of Paradise. Or so my legend says.

sign that she had already entered into the delights of Paradise. Or so my legend says.

In the year Blank, when A-K was governor of the province of R and Good Tibo Krovic had been mayor of the town of Dot for almost twenty years, I had been here twelve hundred years longer, watching.

I am still here, on the very top of the topmost pinnacle of the cathedral named in my honour but also, in some way that I cannot explain, I am standing on a ledge set into that carved pillar which supports the pulpit far, far below. And I am standing on the shield above the door of the Town Hall and painted on the side of every tram and hanging on the wall of the mayor’s office and printed on the front of every notebook that lands on every desk in every classroom in every school in Dot. I am spread-eagled on the bow of that filthy little ferry which arrives, intermittently, from Dash, salt crusted in my ridiculous beard, a woven hemp bumper slung around me like a horse collar.

I am carried on coloured cards in the purses of the women of Dot, blinking at the light as they pass from shop to shop, snoozing in the copper-chinking dark, nestled in kiss curls and baby teeth and souvenir ticket stubs. I hang over beds—beds raucous with wild love, beds chill with indifference, beds where children sleep plump and innocent, beds where the dying lie racked and as thin as string. And I lie here, at the very heart of the cathedral, bare bones wrapped in dry gristle and ancient crumbled silks inside a golden pavilion, studded with jewels, gleaming with enamels, gaudy with ornament, where kings and princes have knelt to weep repentance, where their barren queens have sobbed out pleadings, where the people of Dot stop to pass the time of day with me. I cannot explain this. I cannot explain because I do not understand how I can be in all of these places all the time.

It seems to me that, if it is what I wish, I can be wholly and completely in any one of these places. Everything that is Walpurnia can be here, on top of my cathedral, looking down at the city and far out to sea, or here in the golden box or there on the

front of that particular school notebook. And yet it seems to me that, if it is what I wish, I can be in all of those places at one time, undiluted, not spread one atom thinner, everywhere, watching. I watch. I watch the shopkeepers of Dot and the policemen and the tramps, the happy people and the sad people, the cats and the birds and the yellow dogs and Good Mayor Krovic.

front of that particular school notebook. And yet it seems to me that, if it is what I wish, I can be in all of those places at one time, undiluted, not spread one atom thinner, everywhere, watching. I watch. I watch the shopkeepers of Dot and the policemen and the tramps, the happy people and the sad people, the cats and the birds and the yellow dogs and Good Mayor Krovic.

I watched him as he walked up the green marble staircase to his office. He liked those stairs. He liked his office. He liked the dark wooden panelling inside and the big shuttered windows that looked across the fountains in the square, back up Castle Street to the white mass of my cathedral under its copper-coloured onion dome where, every year, he led the council for its annual blessing. He liked his comfortable leather chair. He liked the coat of arms on the wall with its image of a smiling, bearded nun. Most of all, he liked his secretary, Mrs. Stopak.

Agathe Stopak was everything that St. Walpurnia was not. Yes, she was blessed with long, dark, lustrous hair—but not on her chin. And her skin! White, shining, creamy, utterly wartless. Mrs. Stopak, although she showed me the dutiful devotion proper for any woman of Dot, was not one to take that sort of thing to extremes. In summer, she sat perched on her chair by the window like a buxom crane, dressed in filmy floral prints that sagged on every curve of her body in the heat and moved with every gasp of air that came in at the window.

All winter long, Mrs. Stopak came to work in galoshes and, seated at her desk, she slipped them off and took from her bag a pair of high-heeled peep-toe sandals. Inside his office, poor, good, love-struck Mayor Krovic would listen for the clump of her galoshes when Mrs. Stopak came in to work and rush to fling himself on the carpet, squinting through the crack beneath the door for a glimpse of her plump little toes as they wormed into her shoes.

Other books

Imre: Drago Knights MC (Mating Fever) by Saranna DeWylde

Saved: A Billionaire Romance (The Saved Series Book 1) by Lexi Larue

Blood Rights [Wicked River 2] (Siren Publishing Ménage Everlasting) by Gabrielle Evans

Prizzi's Honor by Richard Condon

Bittersweet Chocolate by Emily Wade-Reid

Vigil by Z. A. Maxfield

Oracle (Book 5) by Ben Cassidy

Training Tessa (Hot Texas Bosses BDSM Erotica) by Sinclair, Lyla

Something Good by Fiona Gibson

Star Toter by Al Cody