The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest (39 page)

Read The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

“Whoever it was, I hope he was a good shot,” Ashley Holden replied.

Kennedy’s accused killer had been to Moscow and Cuba, and was a professed Marxist. What would this do to Dwyer’s careful dismantling of the conspiracy theory? Goldmark feared the worst. But jurors were already with him, Thompson said later. “We knew he’d been screwed,” he told me. “You can’t do that to a guy, no matter what you think of him, and get away with it.” For all the experts brought from distant cities to the small town covered by ice-fog in midwinter, nobody was ever able to connect the ACLU or John Goldmark to a conspiracy to remake America into a totalitarian state. Testimony from twenty years of government Red hunts failed to provide a single nugget to back the claims made against him.

In closing arguments, Joseph Wicks, a defense attorney, again raised the question of why an educated man would choose to live in such wild country. Said Wicks: “He, the brilliant student of government, of political science and of law, of human nature, settles for a cow ranch in Okanogan County where he didn’t know whether apples grew on trees or on a vine, where he didn’t know which end of the cow gave milk or which end of the cow ate the hay.”

The vitriol pouring forth was so strong that Sally Goldmark started trembling. Wicks acknowledged that the smear had riled up the community. “Sure, it creates hatred. And isn’t it about time that we had a little hatred for those people that declare that ‘We will bury you?’ ” Wicks quoted Scripture, then pounded his fist down. “What is God to an atheistic Communist?” At that, Sally burst into tears and ran from the courtroom.

In rebuttal, Goldmark’s attorneys played on the jurors’ sense of decency. Just as a terrible lie could spring from this wide-open country to ruin a man, so could a judgment of simple wisdom and fairness. “Life is only good in a community where freedom and justice are preserved for everybody, not just for a few,” said Dwyer. His colleague, R. E. Mansfield, responded to the venom of Wicks with a Biblical quote of his own. He chose his words from the Book of Proverbs: “A man that beareth false witness against his neighbor is a war club and a sword and a sharp arrow.” Twenty-two years later, the verse would prove to be prophetic.

The Goldmarks won; the first part of this story is an American fable, where truth, justice and tolerance win out over evil. After five days of

deliberation, the jury returned with a verdict against Ashley Holden and Albert Canwell—the largest libel verdict in state history at the time. Gerald Thompson remembers sitting up in the attic of the old concrete-covered Okanogan County courthouse, watching the snow bury his car down below. The jurors were angry at what their community had done to the Goldmarks, he said, and they wanted to make it right. With the verdict, Thompson went back to his orchard near the Canadian border, convinced that never again would anyone call a decent man a traitor in the Okanogan Valley and get away with it.

More than a quarter-century after the trial, R. E. Mansfield is still practicing law in the Okanogan Valley, as he has done since 1937. In his law office hangs a poster-size picture of his hero, Franklin Roosevelt. The valley, slowing down for the winter, looks much the same as it did during the Goldmark trial. But some things have changed. The biggest employer, the timber mill in Omak, has just been purchased by its union employees, making it one of the largest businesses in the West owned by its workers. A worker-owned timber mill—in the old days of the Okanogan Valley such a move would surely be labeled a Communist takeover; today, the local newspaper hails the employee buyout as a bold stroke for community ownership and self-destiny. Mansfield, who faced some lean times after he represented Goldmark, is a beloved figure in the valley; he now plays cribbage with one of his worst enemies, “a guy who hated my guts and believed I was a dyed-in-the-wool Commie.” The John Birch Society, whose members saw Communists behind every apple-storage bin, has all but vanished.

What happened to the Goldmarks—both generations—brings tears to the eyes of a man who is usually never without a joke. Mansfield has never stopped thinking about that family. After the 1963 trial, the Goldmarks recovered their reputation, but never put their lives completely back together. Four years after the verdict, on a cold winter day, John was bucked from a horse in a distant part of the ranch. When Mansfield and others finally found him, he was seriously injured and near death from the onset of hypothermia. Several hip operations failed to restore adequate movement. He moved to Seattle, where he practiced law for several years. After a long fight with cancer, he died in 1979. Six years later, Sally Goldmark died of emphysema just before her oldest son and his family were butchered.

Still, the libel trial had done to the Red Scare what the Scopes monkey

trial had (at least temporarily) done to Creationism. Bill Dwyer wrote a thoughtful and moving account of it titled

The Goldmark Case: An American Libel Trial

. In 1988, after one of the longest delays for any judicial appointee in modern times, Dwyer was approved by Congress as a United States District Court judge in Seattle. During the nearly two years that elapsed after he was first nominated, critics said Dwyer was unqualified to be a federal judge because he had done volunteer work for the ACLU.

Mansfield believes that the Goldmark trial changed life in the Okanogan Valley forever. It had always been the type of open country, in appearance, that could stir poets from Winthrop to Wister. What has changed following the Goldmark trial is that the people opened up a bit, too.

“I don’t think the home folks will rise up in ignorance quite like that ever again,” he says.

But John Goldmark was smeared not so much because he was different, says Mansfield; his crime was that he helped to pry the Okanogan away from the grip of private power. The tragedy that befell him did not fulfill any prophecy of Winthrop’s, though Goldmark was certainly drawn to this country for the very reason cited by the Yankee prophet as a magnet for future generations; rather, the case brought out a truth penned by Richard Neuberger in his 1939 book about the Northwest,

Our Promised Land

.

“Class warfare of a sort has rocked the northwest corner over the principal ways proposed for using America’s greatest block of hydroelectric power,” Neuberger wrote. There were sure to be casualties from the fight over who controls the most elemental resource of the Promised Land, he said, but even with that struggle, the Northwest represented the best hope of America during one of its darkest periods.

Mansfield has seen the promise fulfilled, but he will always be troubled by the price.

“They hated John Goldmark, these guys from the Washington Water Power Company and all their shills,” says Mansfield. “He fought them every step of the way. Then public power came in, the rates came down, and the farmers could afford to pump plenty of water to their orchards. They’d never go back to the way it was. The monopoly days were gone for good. Just too bad a good family had to die for it.”

Chapter 13

C

OLUMBIA

W

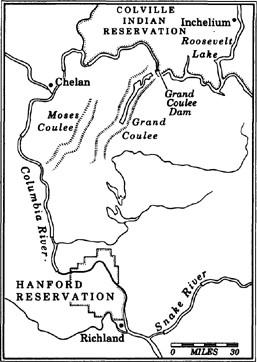

hen the federal government decided to wrestle the Columbia River away from nature and place it in the permanent custody of the Army Corps of Engineers, it did so with some trepidation. Man as a geological force—this was a line that had never been crossed. The land could be altered, customized to human scale, but surely not controlled. And what a way to start: no river in North America except the Mississippi is more powerful than the Columbia; it carries a quarter-million cubic feet of water per second to the ocean, ten times the flow of the Colorado, twice the discharge of the Nile into the Mediterranean. The Corps planned nothing less than radical surgery, a fifty-year operation that would involve ripping open the chest of the Northwest and redirecting the main artery.

Elsewhere, the earth-movers had won a string of significant

victories, cutting a canal fifty miles across the Isthmus of Panama, blasting railroad tunnels through the Rockies and Cascades, stealing water from the High Sierra and the Colorado for delivery to the desert of Southern California. There was no reason scrubland could not be green, or forests leveled to plain, or long-dry coulees filled with fresh water, or dead seas resurrected from salty graves. By the time the West was old and the twentieth century was young, the men from the platoon of progress had little trouble playing God. And so a deity with sliderule and bulldozer took over the Columbia, expecting all mortal elements to fall in place.

Building is the great art of our time, it was said then. And technology, of the heavy-metal, grind-and-grunt school, was king. Salmon were caught in fishwheels and canned by an octo-armed machine called the Iron Chink. Seattle was lopping off its hills, filling in its tidelands and constructing the biggest skyscraper west of the Mississippi. Portland was drawing hydroelectric power from the Willamette and sending forth enough lumberjacks to fell a thousand acres of virgin forest a day. British Columbia was starting work on an ill-fated canal across its interior. The leading citizens of Vancouver, just a few years removed from the mines which made them rich, were planning to tailor their tidelands and gouge open the bordering mountains. Idaho had demonstrated that the unruly Snake River, which brings water from half of the intermountain West to the Columbia, could be dammed to satisfy the interests of a few powerful desert cattlemen and potato farmers. The geo-technicians of the early twentieth century approached the Columbia with the zeal of the first plastic surgeon in Beverly Hills. There was just so much potential.

Problem was, things could be a bit outsized in

the field

, as they called the world outside the drawing room. Take Beacon Rock, the largest monolith of stone on earth except for Gibraltar. Rising from the north shore of the lower Columbia, the rock is the basaltic core of a broken-down Cascade volcano, a piece of vertebra from the spine of the mountain range. Seeking the Pacific, the Columbia long ago smashed through this range, carving out the magnificent gorge and leaving chunks like this along the way. Lewis and Clark named Beacon Rock and admired its stark, vertical beauty. In a New World of magnificent proportions, it seemed to fit. The Corps of Engineers saw it as a nuisance. Although the rock never impeded river traffic, it was just sitting there, not doing anything for anybody, and therefore it was the Enemy. So, the Corps drew up a plan to pulverize the second-largest monolith in the world and use the shattered pieces to build a breakwater at the Columbia’s mouth, thereby accomplishing two enormous tasks at once.

A man named Henry Biddle, a naturalist, new to the Northwest, tried to stop the Corps. He was a descendant of Nicholas Biddle, of Philadelphia, who had edited Lewis and Clark’s journals and later became president of the United States Bank. Unable to dissuade the Corps, Henry Biddle bought Beacon Rock in 1915. The whole thing. For the next three years, he built a path of stone and wood from the base to the summit, a mile-long trail up the nine-hundred-foot vertical length of the rock. He then sold the rock to the state of Washington for one dollar on the provision that it remain a park—and a finger in the eye of the Corps—for eternity. Until recently, it was the only significant battle the Corps of Engineers had lost.

Atop Beacon Rock, the wind out of the west is warm this morning. The vine maple growing from the rock is drained of green and tinged in red, and a few Doug firs, dwarfed by the constant wind, cling to the edge of the monolith, their roots spread out in a pattern that reveals a strained scramble for soil. In a few weeks’ time, the wind will shift the other way, as the colder desert air is sucked into the mild west side of the Cascades. Either way, there is always a breeze in the Columbia Gorge, stiff and new, blowing twenty or thirty miles an hour. The River of the West may have given up its current and most of its independence to the Corps, but the wind has never been touched; carrying the spirit of the old Columbia, it rushes through the Gorge, more dominant than ever.

From this view on Beacon Rock, the Columbia appears as a river of paradox, overwhelmed with responsibility but holding to a few wild quirks of character. To the west, the river is banked by steep, green walls from which pour the torrents of the Cascades. One of these waterfalls, Multnomah, drops 620 feet, pummeling rock and creating a misted mini-rain-forest all around. The Columbia flows these last 140 miles west unimpeded by man, picking up the Willamette, the Sandy, the Lewis, the Kalama, the Cowlitz, the Clatskanie and hundreds of smaller waterways on its final ride to the Pacific. The river below me is far different in appearance from the river an idealistic Franklin D. Roosevelt stared at while he chugged through the Columbia Gorge on a train ride in 1920. Scribbling a speech on the back of his breakfast menu—this was well before handlers scripted every breath for politicians—the young vice-presidential candidate thought about the future of this wild country, picking up where earlier dreamers had left off. In 1813, Jefferson had

envisioned “a great, free and independent empire on the Columbia,” the western edge of an America he called “Nature’s nation.” FDR saw a chance for the common man to live regally within the 250,000 square miles drained by the big river. He wasn’t sure how that would come about, but he wrote that it might have something to do with “all that water running down unchecked to the sea.”