The Grand Ole Opry (15 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

JUDGE HAY:

We put a small price of twenty-five cents on the seats in an effort to handle the crowds, but the auditorium was soon filled

to overflowing. Imagine a theater turning crowds away year after year.

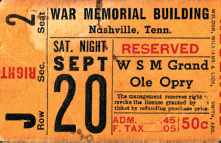

If, as Hay said, the Opry’s first admission charge was a quarter, by 1941, it had increased to fifty cents.

HARRY STONE:

The upholstery at the War Memorial was a gum-chewers’ heaven. Going there set us back ten years. I listened to this committee

spell out all the reasons why we should not only be put out, but put in jail. But it sure was a nice place.

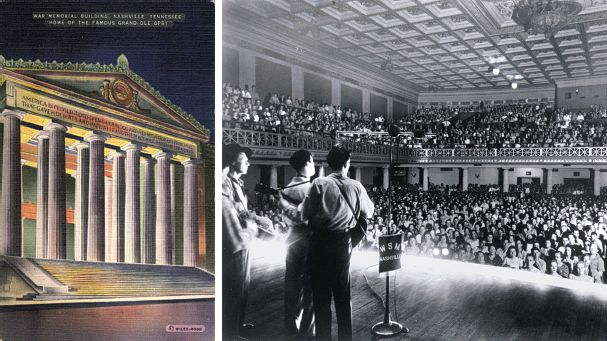

A spectacular venue, Nashville’s War Memorial Auditorium was home to the Opry for almost four years between 1939 and 1943.

Onstage in 1939, Roy Acuff is backed by Bashful Brother Oswald on Dobro.

The War Memorial was close to the State Capitol, and the litter left by the Opry crowd was the last straw. Once again in search

of a home, WSM approached the trustees of the Ryman Auditorium. The Ryman was built in 1892 by Captain Tom Ryman, president

of the Nashville, Paducah, and Cairo Packet Company. It was, Ryman wrote, “purely an outpost to catch sinners.” A reformed

sinner himself, Ryman built the hall so that the evangelist who had turned his life around, the Reverend Sam Jones, might

have a place to preach.

Judge Hay with Sam McGee (holding the sheep) and Lonnie Wilson of Roy Acuff’s Smoky Mountain Boys.

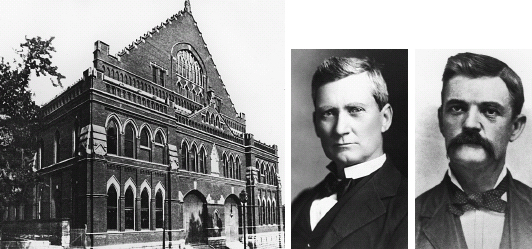

left: The Ryman Auditorium shortly after its construction.

center: Captain Tom Ryman was converted by the Reverend Sam Jones in 1885. The auditorium he built was originally known as

the Union Gospel Tabernacle, but, at Jones’s suggestion, was renamed the Ryman Auditorium after Ryman’s death.

right: Reverend Sam Jones. In the year he converted Ryman (1885), he preached, by his own estimate, one thousand sermons to

three million people. He preached against the theater, trashy novels, cards, baseball, dances, and alcohol. “I will fight

the liquor traffic as long as I have fists, kick it as long as I have a foot, bite it as long as I have a tooth, and then

gum ’em ’til I die,” he said.

JACK D

E

WITT:

The Ryman was run by a group of prominent Nash villians who got no money out of it. They brought in all sorts of plays and

so on. The businessmen who helped run it included Horace Hill [chairman of the local grocery chain, H. G. Hill], Mr. Clements

of National Life, and Dan May, the Jewish manufacturer. We rented it from them. I had to deal with Horace Hill. The first

thing I had to do was find Horace. He never got to his office until five o’clock in the afternoon, and after that we had to

go down and see him and hope that he was there. So he set the amount that we would pay them.

On June 5, 1943, the Opry began at the Ryman on a regular basis. Even with paid admission, every show was sold out with hundreds

turned away every week.

PEE WEE KING:

The reason the Ryman was ideal for the Opry was its acoustics. I don’t know the technical reason why the sound was so incredible,

but I believe the wood in the auditorium absorbed the sound of the music, and it just stayed there. It was like being inside

an old violin, surrounded by good seasoned wood. Not even the backstage noise could destroy the sound. And talk about noise!

It was a free-for-all back there; a lot of the tune-ups and rehearsing took place in full view of the audience. Sometimes,

the only way to tell who was performing was to see who was at the microphone. There were almost no dressing room facilities.

Just one area for men and one for women. There were two washrooms to accommodate as many as two hundred performers.

Crowds started lining up Saturday afternoon for the 8:00 p.m. show at the Ryman.

MINNIE PEARL:

At first, I was horrified by the seeming disorganization. I had come from directing plays. On the Opry, it wasn’t unusual

for an announcer to say, “And now we’re proud to present so-and-so,” and someone would whisper, “He ain’t here, he’s gone

to get a sandwich,” which didn’t fluster the emcee, who’d say, “Oh well, he’ll be back in a minute. Meanwhile, let’s hear

from the Fruit Jar Drinkers.”

Many dreamed of visiting the Opry; some dreamed of playing there.

BUCK WHITE

of the Whites, Opry stars:

First time I came to the Ryman, it was like the first time I’d gone to the Alamo. I thought I was stepping into a holy place.

It was full of spirits. Good spirits.

BILL ANDERSON:

I listened to the Opry as a young boy down in Georgia, and they used to call WSM the “Air Castle of the South,” so I always

thought the Opry was held in a castle. The first time I came I was about fourteen, and I was so disappointed because I had

visions of this big castle sitting out on a big piece of land. And here was this little auditorium on Fifth Avenue. It was

falling apart and there were holes in the curtains, and I thought, This isn’t the castle of my dreams at all. We had seats

downstairs under the balcony. My mother had bought a new dress to go to the Opry, and someone spilled a soft drink upstairs

and it leaked down on her new dress. Once the curtain opened and the music started, I didn’t care. It wasn’t broken down into

two different shows then, but by 10:30 my mom and dad and sister had had enough and they went back to the hotel. I said, “Not

me.” I sat there until midnight, then walked around the corner to the Ernest Tubb Record Shop for the Midnite Jamboree. I

was just like a sponge soaking it all up, but getting into that business was a dream I didn’t dare dream.

The Ryman stage from the Confederate Gallery.

WILLIAM R. M

C

DANIEL

and

HAROLD SELIGMAN,

journalists:

Although the show lasts from 7:30 p.m. until twelve midnight, many of the fans sit through the entire program. Others leave

about ten, after they have seen most of the performers. As a rule, the entertainers appear at least once before ten, and once

again after ten. This makes room for many of the throng who wait outside the auditorium in the hope of getting a seat in the

last portion of the show. The turnover in audience permits the show to play to an average audience of five thousand. Demand

for tickets is greater in the summer months, and the show is sold out many weeks in advance. Fans holding general admission

tickets begin lining up in front of the auditorium by the middle of Saturday afternoon to assure themselves choice seats when

the doors are opened at six. By that time, crowds are usually lined up eight abreast for two blocks. Audience turnover is

higher in the summer, mainly because it gets steaming hot in the auditorium, despite exhaust fans, personal cardboard fans,

and shirtsleeves.

Jim Denny, who’d been the Opry’s bouncer at the Dixie Tabernacle, realized that there was some money to be made from the crowds

before they got to see the show. “Denny,” wrote journalist George Barker, “had the genius of being able to do a little something

for himself all the time he was doing a first-rate job for his boss.”