The Grass is Singing (29 page)

She felt she had only to move forward, to explain, to appeal, and the terror would be dissolved. She opened her mouth to speak; and, as she did so, saw his hand, which held a long curving shape, lifted above his head; and she knew it would be too late. All her past slid away, and her mouth, opened in appeal, let out the beginning of a scream, which was stopped by a black wedge of hand inserted between her jaws. But the scream continued, in her stomach, choking her; and she lifted her hands, claw-like, to ward him off. And then the bush avenged itself: that was her last thought. The trees advanced in a rush, like beasts, and the thunder was the noise of their coming. As the brain at last gave way, collapsing in a ruin of horror, she saw, over the big arm that forced her head back against the wall, the other arm descending. Her limbs sagged under her, the lightning leapt out from the dark, and darted down the plunging steel.

Moses, letting her go, saw her roll to the floor. A steady drumming sound on the iron overhead brought him to knowledge of his surroundings, and he started up, turning his head this way and that, straightening his body. The dogs were growling at his feet, but their tails still swung; this man had fed them and looked after them; Mary had disliked them. Moses clouted them back softly, his open palm to their faces; and they stood watching him, puzzled, and whining softly.

It was beginning to rain; big drops blew in across Moses' back, chilling him. And another dripping sound made him look down at the piece of metal he held, which he had picked up in the bush, and had spent the day polishing and sharpening. The blood trickled off it on to the brick floor. And a curious division of purpose showed itself in his next movements.

First he dropped the weapon sharply on the floor, as if in fear; then he checked himself and picked it up. He held it over the verandah wall under the now drenching downpour, and in a few moments withdrew it. Now he hesitated, looking about him. He thrust the metal in his belt, held his hands under the rain, and, cleansed, prepared to walk off through the rain to his hut in the compound, ready to protest his innocence. This purpose, too, passed. He pulled out the weapon, looked at it, and simply tossed it down beside Mary, suddenly indifferent, for a new need possessed him.

Ignoring Dick, who was asleep- through one thickness of wall, but who was unimportant, since he had been defeated long ago, Moses vaulted over the verandah wall, alighting squarely on his feet in the squelch of rain which sluiced off his shoulders, soaking him in an instant. He moved off towards the Englishman's hut through the drenching blackness, water to his calves. At the door he peered in. It was impossible to see, but he could hear; holding his own breath, he listened intently, through the sound of the rain, for the Englishman's breathing. But he could hear nothing. He stooped through the doorway, and walked quietly to the bedside. His enemy, whom he had outwitted, was asleep. Contemptuously, the native turned away, and walked back to the house. It seemed he intended to pass it, but as he came level with the verandah he paused, resting his hand on the wall, looking over. It was black, too dark to see. He waited, for the watery glimmer of lightning to illuminate, for the last time, the small house, the verandah, the huddled shape of Mary on the brick, and the dogs who were moving restlessly about her, still whining gently, but uncertainly. It came: a prolonged drench of light, like a wet dawn. And this was his final moment of triumph, a moment so perfect and complete that it took the urgency from thoughts of escape, leaving him indifferent. When the dark returned he took his hand from the wall, and walked slowly off through the rain towards the bush. Though what thoughts of regret, or pity, or perhaps even wounded human affection were compounded with the satisfaction of his completed revenge, it is impossible to say. For, when he had gone perhaps a couple of hundred yards through the soaking bush he stopped, turned aside, and leaned against a tree on an ant-heap. And there he would remain, until his pursuers, in their turn; came to find him.

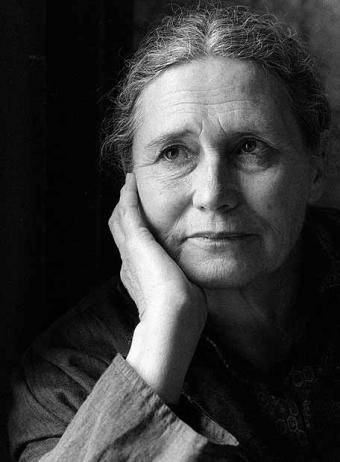

Doris Lessing

Doris Lessing was born of British parents in Persia in 1919 and was taken to Southern Rhodesia when she was five. She spent her childhood on a large farm there and first came to England in 1949. She brought -,kith her the manuscript off her first novel, The Grass is Singing, which was published in 1950 with outstanding success in Britain, in America, and in ten European countries. Since then her international reputation not only as a novelist, but as a nonfiction and short-story writer has flourished.

For her collection of short novels, Five, she was honored with the Somerset Maugham Award. She was awarded the Austrian State Prize for European Literature 1981, and the German Federal Republic Shakespeare Prize of 1982.

Among her other celebrated novels are the five-volume Children of Violence series, The Golden Notebook, The Summer Before the Dark, and Memoirs of a Survivor.

Many of her short stories have been collected in two volumes entitled To Room Nineteen and The Temptation of Jack Orkney; while her African stories appear in This Was the Old Chief’s Country and The Sun. Between Their Feet.

Shikasta, the first in the series of novels with the overall title of CANOPUS IN ARGOS: was published in 1979; the second; ‘The Marriages Between Zones’ Three, Four, and Five, in 1980; the third; ‘The Sirian Experiments’, in 1981, when it was short-listed for the Booker Connell Prize; the fourth; ‘The Making of the Representative for Planet S’, in 1982; and the fifth; ‘The Sentimental Agents in the Volyen Empire’, in 1983.

Other books

Forever Her Champion by Suzan Tisdale

Six Feet Over: Adventures in the Afterlife by Mary Roach

Kindred (The Watcher Chronicles #2) by S.J. West

The Humanity Project by Jean Thompson

Taming the Elements: Elwin Escari Chronicles: Volume 1 by David Ekrut

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals by Dan Abnett, Nik Vincent

One False Note - 39 Clues 02 by Gordon Korman

Zero Hour by Andy McNab

Novel 1968 - Brionne (v5.0) by Louis L'Amour

Best Friends Through Eternity by Sylvia McNicoll